10 countries with highest malnutrition burden in children

Global acute malnutrition in children aged 6-59 months, 2024 data

Only five per cent of adults consume the WHO-recommended five servings of fruits and vegetables per day

In Summary

Audio By Vocalize

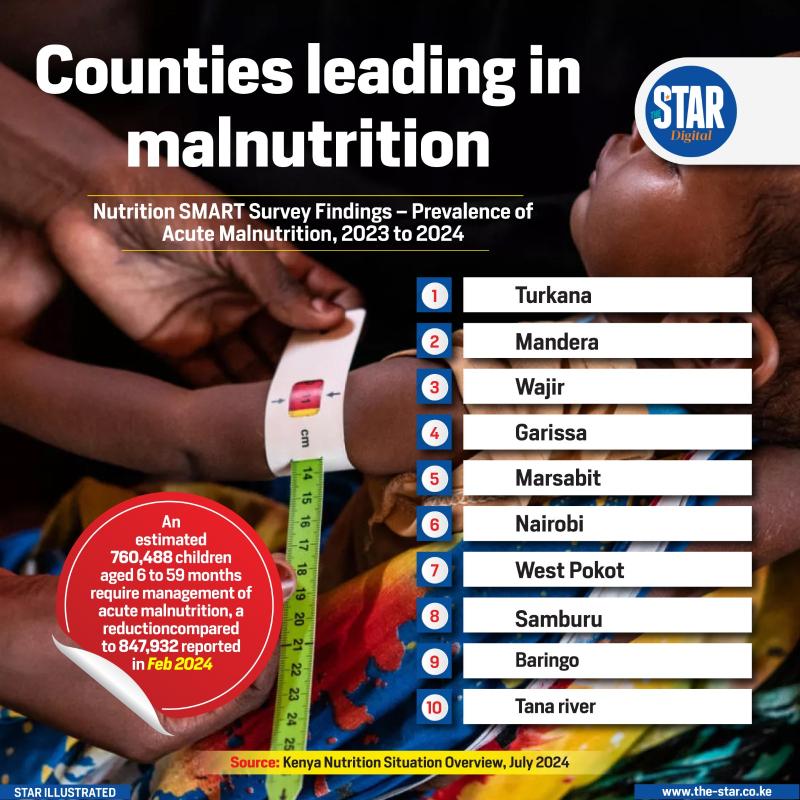

Counties leading in malnutrition.

Counties leading in malnutrition. Kenya has made significant progress in improving nutrition over the past two decades, including cutting childhood stunting nearly in half and achieving near-universal salt iodisation.

Yet, the country continues to face a triple burden of malnutrition (undernutrition, micronutrient deficiencies and rising overweight and obesity), which threatens public health, productivity and economic growth.

Experts warn that malnutrition costs the economy nearly seven per cent of GDP annually and risks undermining the nation’s development goals unless urgent, multisectoral action is taken.

Veronica Kirogo, head of the division of Nutrition and Dietetics at the Ministry of Health, pointed out that good nutrition is the foundation for health, productivity and economic growth.

“Every dollar invested in nutrition yields $22 in returns,” she said.

Kirogo stated that Kenya still struggles with the triple burden, with anaemia at 41.6 per cent among pregnant women and 26.3 per cent among preschool children.

Folate deficiency stands at 32.5 per cent among pregnant women and zinc deficiency at 80 per cent among children and women.

“Progress has been made in reducing stunting, which dropped from 36 per cent in 2003 to 18 per cent in 2022. However, disparities remain wide: Kilifi, West Pokot and Samburu record some of the highest rates, while Garissa and Kisumu have as low as nine per cent,” she said.

Kirogo noted that dietary diversity remains poor. The 2015 Kenya Stepwise Survey found that only five per cent of adults consume the WHO-recommended five servings of fruits and vegetables per day. The average intake is just two servings, while 19 per cent of adults consume none at all.

According to the 2022 Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS), only 49 per cent of women meet minimum dietary diversity. Seventy per cent regularly consume sweetened beverages and 35 per cent eat unhealthy foods.

She further indicated that the economic and social costs of malnutrition are staggering. Malnourished children often face poor school performance, absenteeism and health challenges, while the workforce suffers from reduced productivity.

According to the 2014 KDHS, Kenya loses an estimated Sh373.9 billion annually, which is 6.9 per cent of GDP, due to malnutrition-related health, education and productivity losses.

“Scaling up 11 key nutrition interventions in all counties would cost Sh9.8 billion ($76 million) but could generate Sh59.2 billion ($458 million) in annual economic returns,” she said.

Kirogo noted that despite the challenges, Kenya has recorded significant progress in nutrition. Stunting declined from 26 per cent in 2014 to 18 per cent in 2022, while exclusive breastfeeding rates have risen to 60 per cent. Vitamin A supplementation coverage now exceeds 80 per cent, and 99 per cent of households consume adequately iodised salt.

She added that food fortification efforts have also improved, with compliance in maize flour rising from 16 per cent in 2017 to 46 per cent in 2021 and wheat flour compliance increasing from 18 per cent to 84 per cent over the same period.

“The country has also rolled out Baby Friendly Community Initiatives in over 1,500 community units, strengthened nutrition information systems and developed scorecards and reporting tools,” she said.

“However, gaps persist, especially in financing (heavy reliance on donors), service delivery (limited coverage across the life course), inadequate nutrition professionals, weak enforcement of policies and equity gaps as nutritious foods remain unaffordable for many. Diets are still cereal-heavy, while myths, misinformation and unchecked marketing of unhealthy foods worsen the situation.”

Ruth Okowa, country director of the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, warned that alongside undernutrition, overweight and obesity are rising rapidly.

“More Kenyans, both young and old, are now at risk of diet-related non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases,” she said.

These trends, Okowa added, not only strain health systems but also erode family incomes and threaten future generations.

Since 2010, Gain has been working with the government and partners to transform food systems for healthier diets, guided by its 2023–2027 Business Plan, which aims to improve access to healthier diets for over 7 million Kenyans.

The organisation supports nutrition policy implementation in Nakuru, Nairobi, Nyandarua, Mombasa, Machakos and Kiambu counties by strengthening stakeholder platforms, tracking budgets, engaging the media and linking vulnerable households to social protection programmes.

She said Gain is also working with the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development on the National Agrifood Systems Investment Plan, as well as the MoH on the Kenya Nutrient Profile Model (KNPM), which helps regulate labelling and marketing of unhealthy foods, particularly to children.

“At county level, Gain is supporting the development of Food Safety Policies and Bills to reduce foodborne illness and improve access to safe, nutritious food,” she said.

Okowa stressed the need for urgency, stating; “Together, we can make good nutrition not just a health agenda, but a national priority.”

Instant analysis

The 2022 Kenya Demographic Health Survey (KDHS) shows that 18 per cent of children under five are stunted. 10 per cent are underweight, three per cent are overweight or obese and 42 per cent of pregnant women suffer iron deficiency anaemia.

Global acute malnutrition in children aged 6-59 months, 2024 data