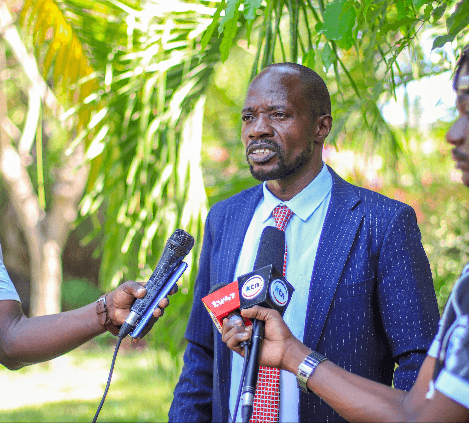

Peter Mwangi during the 2023 Kip Keino Classic/HANDOUT

Peter Mwangi during the 2023 Kip Keino Classic/HANDOUT

From Eliud Kipchoge’s prowess in the marathon to Faith Kipyegon’s devastating kicks on the track, the country’s global reputation is synonymous with excellence in distance running.

But beyond the roads and tracks, another class of athletes have been carving out their own space in the realm of field events.

Top on that list is Kenya’s javelin ace Julius Yego, famously nicknamed “The YouTube man” for his self-taught skills.

Yego took the world by storm in 2015 when he captured the global title with a lifetime best throw of 92.72m in Beijing, China, before extending Kenya’s field dominance at the Rio 2016 Olympics by bagging silver (88.24m) behind Germany’s Thomas Rohler (90.30m).

However, another crop of field athletes is emerging in the shot put, hungry to dominate not just the continent but the world.

Towering above them all in the shot put ring is Peter Mwangi, a man as resilient as he is powerful, and arguably Kenya’s most accomplished shot-putter.

The former boxer and three-time national shot put champion is slowly but surely making sure the heavy iron ball gets its place on the national radar.

Shot put is one of athletics’ most gruelling yet often underappreciated disciplines, an explosive contest where athletes hurl a dense metal sphere as far as is humanly possible.

What makes the event uniquely demanding is the rare blend of brute strength, technique and focus.

Physically, it requires immense power, particularly in the legs, core, and upper body, to generate the momentum needed to launch the heavy shot.

Throwers must harness explosive speed and precise timing. Maintaining balance and body control throughout the throw is critical to achieving maximum distance and avoiding fouls.

Apart from brute strength, mental fortitude is key as one slight misstep in footwork or a lapse in concentration can cost an athlete everything.

The highlight of Mwangi’s career was winning a gold medal at the World Masters Indoor Championships in Gainesville, Florida, USA, held from March 23 to 30.

Mwangi posted a 14.79m throw in the M40 category to clinch gold ahead of Americans Pierre Brown (13.18m) and Robert Horton (12.71m).

The father of three had not expected to clinch gold.

“I was not expecting to win gold. This was my first indoor championship and I was not used to the field and atmosphere. Those whom I was competing against were tough since they were used to the indoor games,” Mwangi reveals.

“I was the first Kenyan to compete at the championships and I did not want to let the country down, so I decided to go for it and I am glad I won gold.”

Despite his many achievements, Mwangi is not content.

His next goal is audacious yet inspiring, breaking the long-standing national shot put record of 18.19m, set by Robert Welikhe in 1989.

“My dream would be to break the national shot put record next season,” he says.

“This season is practically over for us. I will have to switch my programme. Going for that mark will require me to be at my best,” he states.

Mwangi boasts a personal best of 16.78m set during the World Masters Indoor trials at the Kenyatta University grounds on November 23, 2024.

The Sergeant stationed at the Nairobi West Prison is well aware of the steep hill the discipline faces in the country.

The global qualifying mark for the 2025 World Championships in Tokyo stands at 21.50m, far above what Kenyan throwers are currently producing.

“The mark for the World Championship qualification in Tokyo has been set too high. We are throwing 16m in the country, no one is above the 17m mark. That 21.50m is way high at the moment,” he notes.

With the nation still miles away from global dominance, Mwangi is in the driver’s seat to ensure Kenyan shot put throwers burst their way into the international debate.

“In the field events, we only recognise the javelin because of Yego. So the sport is given more priority. We would also like to see the shot put given as much attention since there is vast talent in the country,” Mwangi states.

Born on October 11, 1983, in Solai town, Nakuru County, Mwangi’s journey wasn’t carved on a traditional path.

In 2007, he joined the Kenya Prisons Service, but it was inside the boxing ring that he first chased sporting glory, competing in the heavyweight division between 2010 and 2013.

“At first, I was a boxer in the heavyweight division. I used to represent Prisons in various competitions. I would get to the nationals, but unfortunately, the competition was intense,” he observes.

“Boxing was tough, to be honest. One could get beaten a lot and the pay was not that good. Compared with what I am receiving now during the Athletics Kenya meetings, the pay in boxing was minimal,” Mwangi states.

A serious rib injury in 2013 was the final blow to his boxing career. While recovering in the hospital with little support and no incentives, Mwangi had a revelation.

“In my last fight, my ribs were shattered, sending me to the hospital. I was not taken care of that well while there. I decided to quit. It was becoming frustrating to put your body on the line and get nothing in return,” Mwangi recalls.

“That year, I decided to represent Nairobi West in the inter-station games and I was able to throw 9m and made the cut to the Nairobi team. I saw that I had good talent in the shot put and I decided to put my focus into it,” he notes.

Recognising his raw talent, Kenyan athletics legend Elizabeth Olaba took him under her wings in 2015.

Olaba, who holds the women’s national shot put record of 15.60m set in 1987, instilled discipline, technique and belief in Mwangi.

“Olaba saw my talent and recruited me to start training under her. She has guided me all through my career up to this point,” Mwangi reveals.

Mwangi’s breakthrough came in 2018 when he captured the national title with a 15.56m throw on his debut at the Athletics Kenya National Championships, announcing his arrival on the big stage.

Boaz Monyancha (15.43m) and Benson Maina (15.33m) completed the podium.

“I was confident that with the training I had undertaken, I would emerge victorious, and I did,” he notes.

The following year, he narrowly missed out on defending his title, finishing second with a throw of 15.33m behind Maina (16.47m).

Mwangi, however, took positives from that setback and pushed on with zeal and determination, ultimately earning an invitation to the 2021 Kip Keino Classic World Continental Tour.

In that meeting, Mwangi threw 15.72m to clinch victory ahead of Maina (15.68m) and Leonard Bett (14.09m).

In 2022, Mwangi recaptured his national title with a 16.29m throw before going on to claim a double in 2023 — a third national title (15.83m) and the Kip Keino title (16.25m).

In 2024, Mwangi missed out on the 16.99m entry mark for the African Games in Ghana after posting 15.64m at the trials at Nyayo Stadium.

However, he did not let that stop him. He went on to clinch his third Kip Keino title with a 15.50m throw ahead of Maina (15.34m) and Bett (14.99m).

“I was just from the hospital where I had had surgery on the appendix. I did not expect to win. I just pushed myself and it all worked out in the end,” Mwangi notes.

Mwangi is a keen follower of German athlete David Storl, the 2012 Olympic silver medallist, whom he views as his role model.

“I follow Storl on social media and do what he does more so in terms of strength and gym work,” he says.

However, challenges abound. Shot put is a demanding discipline, both physically and financially.

“Shot put requires a lot of gym work. To access a gym, we have to dip into our own pockets — roughly Sh800 a day. Our training regimen requires three days of gym work to total about Sh2,500 a week, which is quite expensive,” he notes.

Even more frustrating is the lack of international exposure.

“I have been in this sport for a while now and we have not had chances to go out and compete against athletes from other countries. Competing against top athletes sharpens your form and increases your skills. I would call on AK to find us competitions outside the country,” he pleads.

A lack of proper facilities is also a major hindrance.

“I train at the Nairobi West grounds but there are some athletes who don’t have proper training grounds and with the closure of Nyayo and Kasarani, that becomes a big concern,” he says.

Still, there is a glimmer of hope. Mwangi, alongside friendly rival Maina, have quietly sparked a competitive renaissance in the discipline. The two often trade titles, pushing each other to new levels.

“We have a friendly rivalry with him (Maina). He beats me in some events and I beat him in others. That makes the event more competitive. Seeing younger athletes getting involved as well is inspiring,” he says.

“We have more than five athletes throwing 15m and above, which shows that the competition is getting intense.”

Off the field, Mwangi’s heart beats for the next generation. He trains a team of visually impaired para-powerlifters.

“I have a small group of visually-impaired athletes I train in powerlifting. Last month, we participated in the IBSA Powerlifting and Bench-press World Championships in Kazakhstan, where I had a team of 12 athletes that were able to amass 35 medals,” he boasts.

Mwangi hopes to venture into shot put coaching once he retires.

“I would want to coach the nation’s next talents in the shot put once I retire... to give back and ensure the sport develops and grows,” he concludes.