In early 1982, treason began with a whisper in the wind-blasted barracks of Nanyuki Airbase, a hush shared between two uniformed silhouettes beneath an aircraft hangar.

Here, Snr Sgt Pancras Akumu lit the fuse of rebellion in the

heart of Kenya’s northern skies.

In the corridors of the Kenya Air Force, amid rusting

vehicles and muted radios, a quiet fire began to spread. The government, they

claimed, had gone rogue.

And the redemption?

It would come from the skies.

“The sound of freedom,” they said.

But this wasn’t your ordinary mutiny. It was an engineered

expedition powered by reckless ambition, raw bravado, radios in fire trucks,

tape decks and borrowed microphones.

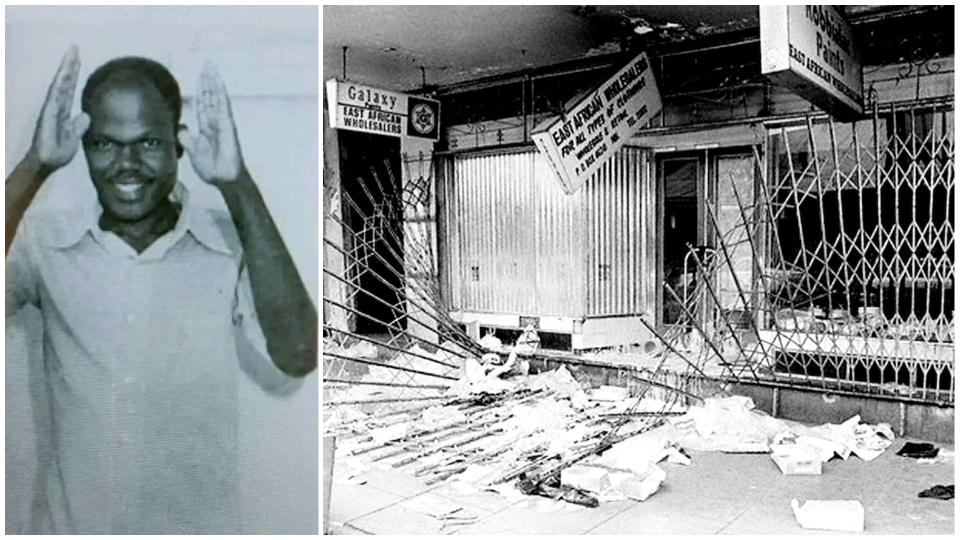

At its planning helm stood Akumu, the charismatic, daring

and ultimately doomed senior non-commissioned officer.

By early 1982, within the air force, many airmen came from

working-class backgrounds and held diplomas in avionics, engineering and radar

systems. They were trained, politically conscious and in some cases,

radicalised by external ideologies, from Nkrumahist Pan-Africanism to

Gaddafi-style “people’s revolution”.

The idea of military-led liberation had roots. Across the

continent, coups had altered national destinies: in Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria

and Uganda. To men like Snr Sgt Akumu, the Kenyan military, especially the Air

Force, could replicate such acts.

In early 1982, the Nanyuki Airbase was a distant military

outpost. But within its warrant officers’ and sergeants’ mess hall and

corporals’ club and airmen's club, a small cadre of airmen was fermenting

treason.

Snr Sgt Akumu and Sgt Joseph Ogidi became the architects of

what they branded the People’s Redemption Council, a secret fraternity

committed to the overthrow of the Kenyan government.

Further away in another airbase in Nairobi, Snr Pvt Hezekiah

Ochuka was doing a similar task.

The movement spread with the stealth of a virus.

From Eastleigh to Embakasi, from Lanet to Kisumu, whispers

turned into promises, and promises into oaths.

Recruitment meetings masqueraded as card games. Briefings

were held over cheap beer and nyama choma. Oaths were sealed not with ceremony,

but with threats and cash incentives.

In one incident, Akumu handed out Sh11,000 — blood money for

a cause painted as “patriotic” — to lure recruits This wasn’t mere largesse; it

was the trail of shadow financiers behind the veil of civilian sympathisers and

covert donors.

RECRUITMENT PROCESS

From the beginning, the coup plotters understood that

ideology alone could not topple a government.

They needed men, ones who were committed, armed and ready to

defy both command and constitution. But because they could not recruit the

officer corps, they started from the other ranks.

Akumu and Ogidi launched an aggressive recruitment drive.

Their targets were carefully chosen: young servicemen in the Kenya Air Force

and disgruntled army personnel across Nanyuki, Eastleigh, Embakasi and the 81

Tank Battalion in Lanet.

Recruitment was not just verbal; it was spiritual and

psychological.

Meetings took place across the country, in barracks, homes

and bars. Soldiers were offered drinks, cash and most crucially, oaths of

secrecy. Once inducted, they were warned that betrayal would mean certain

death.

To ensure long-term success, Akumu aimed for the brass (the

Officer Corps), hoping to win over pilots and commanders who could provide

aerial superiority. But most officers were either cautious or loyal to the

regime.

In fact, one of the earliest signs of the group’s intent

surfaced in March or April 1982, when Akumu and Ogidi approached Capt Jeclin

Agola at his house in the Nanyuki compound. They requested his help in

identifying and recruiting pilots.

Agola was stunned.

He rejected their offer and threatened to report them to

higher authorities. Akumu begged him not to; he wasn’t ready to be exposed.

The fragility of their plan was evident: too soon, and the

whole enterprise would crumble.

One of the earliest and most active figures in the

recruitment drive was Sgt Joseph Obuon.

His involvement in actively bringing personnel into the fold

is noted as early as April 1982. Obuon undertook significant travel, visiting

various military installations to discreetly or openly recruit individuals to

the cause of overthrowing the government.

For instance, he made a notable visit to Sgt Richard Guya in

Gilgil, where he discussed the recruitment of military personnel for the plot.

This indicates a deliberate and systematic effort to build a network of

sympathisers and active participants across different units.

PEOPLE’S REDEMPTION COUNCIL

As the conspiracy gained momentum, a leadership structure

began to emerge.

The plotters envisioned a new governing body, which they

named the People’s Redemption Council (PRC). This name itself suggested an

ideological motivation, portraying their actions as a liberation or redemption

of the nation from its current leadership.

Snr Pvt Hezekiah Ochuka soon emerged as a central figure,

largely taking on the role of the primary orchestrator and eventual figurehead

of the coup attempt. However, his rise to leadership was not without internal

contention.

There was a significant power struggle, particularly with

Sgt Joseph Obuon, over the chairmanship of the PRC. Obuon, brandishing his

senior non-commissioned officer rank, asserting his extensive recruitment

efforts, and even citing his position as chairman of the airmen's mess,

believed he had a stronger claim to lead.

Obuon could not understand how a private would be the leader

of the movement, while there were sergeants and senior sergeants in their

midst.

This led to a heated debate that almost broke into a fight,

underscoring the volatile internal dynamics among the plotters even before

D-Day.

It was Snr Sgt Pancras Akumu who reportedly intervened in

this dispute, advising Obuon to cede the chairmanship to Ochuka. Akumu's

rationale, chillingly, was that they could then kill Pvt Ochuka once the coup

had successfully taken place.

By May 1982, the PRC had grown into a multi-regional

underground network. Its operational nerve centre was the Nairobi house of

Ochuka, located in Umoja Estate, House K-27.

In that cramped residence, conspirators pretended to play

cards as cover for detailed revolutionary briefings. Beneath the clink of soda

bottles and cigarette smoke, a rebellion was being shaped.

Meetings were structured. Progress reports were demanded.

Every member had a sector, a role, a responsibility.

When Akumu gave his report on the Nanyuki wing, he revealed

plans to use radios fitted in fire trucks for communication on D-Day. Ochuka,

unimpressed, urged Akumu to do better. “You must work harder and improve your

section’s readiness,” he said.

Ashamed, Akumu returned to Nanyuki and intensified

operations.

By June, more meetings followed. Witnesses later testified

how soldiers casually read newspapers while pretending to relax at Ochuka’s

house. But inside, they were debating failures in communication, missing gear

and recruitment shortfalls.

Akumu was quietly absorbing it all, sharpening his section’s

preparations, identifying loyalists, stockpiling morale and spreading the

doctrine of uprising.

He was building an insurgency from scratch, a dangerous

blueprint hidden in plain sight.

EXPANDING THE REACH

On May 8, 1982, Akumu made a decisive move. He travelled to

Kisumu, widening the PRC’s reach into western Kenya.

The meeting took place in a modest house, its ownership

still undisclosed. But what happened inside was clear: a high-level planning

summit.

Attendees included Akumu, Ochuka, Ogidi a mysterious

civilian named “Langi”, and the homeowner, described in court as an “old man”.

Court testimony confirms the session was closed-door and

strategic. The objective: to align regional efforts and discuss fallback

strategies. Kisumu would serve as a secondary operations post, a support cell

if Nairobi failed to fall.

Witnesses described the house as tense, conversations

hushed. The idea of bombing Nairobi was already circulating. Military radios,

press coverage and the timing of airstrikes were all part of the agenda.

Akumu was no longer just a recruiter. He was a tactician, a

messenger, a coordinator, moving ideas like ammunition across Kenya’s

geography.

By mid-July, Akumu’s mission shifted from recruiting to

ideological activation.

In Nakuru town, he met with members of the 81st Tank

Battalion from Lanet at Salwe Bar and Shirikisho Lodging.

In these smoke-filled joints, over drinks and whispers,

Akumu presented the coup as a moral obligation. The target wasn’t Nairobi, it

was Nakuru town, a vital logistics node in the Rift Valley.

He issued oaths of allegiance to men like Snr Pvt Abich and

Pvt John Agallo, invoking cultural memory, military honour and revolutionary

duty. Betrayal, he warned, would result in “execution”.

The next day, outside Amingos Bar, Akumu reiterated the

plan:

“When the coup begins, take Nakuru immediately. Show no

resistance. Move quickly.”

On July 19, 1982, the final pre-coup mobilisation was

recorded at Nanyuki Air Base. This was the belly of the beast, where it all

began.

Akumu convened a last gathering with soldiers from the base,

including Pvt Tom Okwengu and Snr Pvts Juma Ooko and Akoko.

His message: “The hour has come. The Kenya Air Force is

ready to take over.”

To sweeten allegiance, he and Ogidi provided food, drinks

and cash bribes. They issued threats cloaked in fraternity and made recruits

swear loyalty to the cause. According to testimony, one Pvt Obell was given

Sh11,000 to help bring in more soldiers.

Where did the colossal amount of money come from? Witnesses

pointed to civilian financiers, possibly sympathetic businessmen or

ex-soldiers; quiet sponsors of Kenya’s great gamble.

By the end of July, everything was ready: The Voice of Kenya

transmission stations had been mapped; The Langata Barracks, Department of

Defence, Army Headquarters, General Post Office, Kenya Air Force Eastleigh,

State House, Broadcasting House and GSU Ruaraka were identified as key targets;

Cells in Kisumu, Nakuru and Embakasi were on alert; Air Force pilots were to be

“tasked” with bombing strategic sites if resistance mounted.

The last point proved difficult as the coup had been

organised outside the Officer Corps, who were the trained pilots. Sidelining

these officers alienated the very people who held technical expertise,

operational authority and institutional credibility.

Only one thing remained: the date.

Excerpt from the forthcoming book: 1982: The [Attempted] Coup That Shocked Kenya, By Barmoiben Korir. It will be available on Amazon Bookstore in 2027. Capt (Rtd) Barmoiben Kipkemoi Araap Korir is a retired military officer and author of several cultural and historical books.