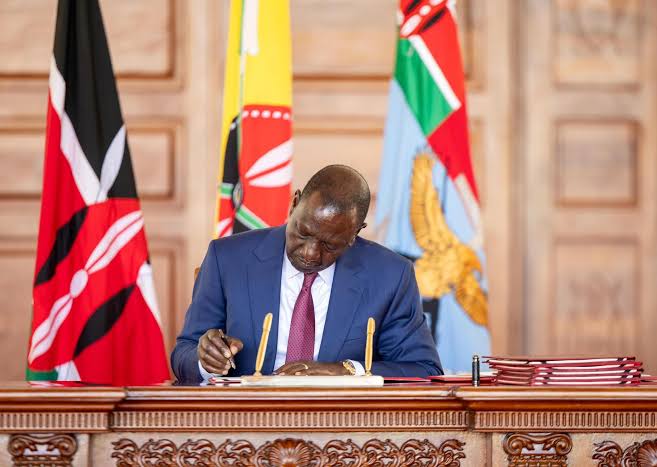

President William Ruto signs into law the Land (Amendment) Bill, 2024 at State House Nairobi on October 15, 2025./PCS

President William Ruto signs into law the Land (Amendment) Bill, 2024 at State House Nairobi on October 15, 2025./PCSSummary and Historical Context:

On 15th October 2025, President William Ruto assented to the Land (Amendment) Bill, 2024, transforming it into law.

The Bill, sponsored by MP Simon King’ara, was passed by the National Assembly in March 2024 and the Senate in August 2025, after incorporating amendments requiring county consultation in land acquisitions.

It was signed alongside seven other legislative instruments.

This enactment immediately ignited heated debate that has now been amplified

across public platforms, editorials, and social media threads.

At the centre of the controversy lies an impassioned critique by Professor Gitile Naituli, who portrays the new law as a “quiet coup” against Kenya’s sovereignty, a legislative regression that would convert landowners into tenants and revive colonial modes of dispossession.

The emotive appeal of such a claim is understandable as Kenya’s land memory is deeply wounded and etched with the injustices of the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1915 and the violent reclamation struggles of the Mau Mau era.

Yet, as powerful as these historical echoes are, they should not obscure the present reality. A close, evidence-based reading of the Land (Amendment) Act, 2024 reveals that this law neither erodes devolution nor strips ancestral ownership but rather, it modernizes land administration, enhances transparency and tightens accountability in ways long overdue.

Kenya’s land question has always mirrored its political evolution. Colonial ordinances such as the Crown Lands Ordinance (1915) alienated vast tracts of fertile land, exiling African communities into “native reserves” and sowing the seeds of rebellion. Independence did not immediately resolve these distortions as post-colonial administrations often reproduced exclusion through opaque allocations and elite capture under the banner of “development.”

The 2010 Constitution sought to rupture this legacy. It categorised land into public, private, and community (Articles 61–64), anchored land ownership in equity and sustainability (Article 60), vested public land in the people of Kenya to be administered by the National Land Commission (Article 62), and limited non-citizen ownership to leaseholds of 99 years (Article 65). This framework was designed as a bulwark against both historical injustice and future abuse.

The Land (Amendment) Act, 2024 stands firmly within this constitutional lineage. It amends the Land Act, 2012 and related statutes not to centralise power, but to operationalise constitutional mandates by clarifying tenure, codifying gazettement requirements and embedding public accountability mechanisms to combat the endemic opacity that has long defined land transactions.

Debunking the Myth of Centralization

Professor Naituli’s gravest accusation is that the law “dangerously centralises” land control, recentralising decision-making in Nairobi and hollowing out the spirit of devolution. Yet this interpretation collapses upon closer scrutiny.

The Act introduces mandatory gazettement of all public land registrations which is an innovation designed precisely to prevent unilateral allocations and backdoor alterations. County governments retain full authority over local land rates and development control under Article 209 and the Fourth Schedule of the Constitution.

The National Land Commission continues to investigate irregularities under Article 67(2)(e), while the Ministry of Lands’ enhanced role remains administrative, not executive.

The courts have similarly recognised this cooperative model by upholding that Cabinet Secretary powers over compulsory acquisition is constitutional provided the NLC’s oversight remains intact. Devolution, then, thrives through coordination, not isolation.

Far from

stripping counties of power, the Act modernises operations through digitisation

(for example, Ardhisasa), curbing graft that previously thrived in bureaucratic

silos. It builds upon, not betrays, the Land Laws (Amendment) Act, 2016,

which survived similar centralisation critiques.

“The law converts freehold owners into tenants” and introduces taxes on freehold land which will cause mass dispossession

One of the most incendiary rumours is that the Act introduces new taxes on freehold or ancestral land, transforming ownership into tenancy. This is unfounded. The 2024 law contains no provision imposing fresh levies on private or agricultural freehold land.

The claim that the Act converts millions of Kenyans’ freehold titles into leaseholds, thereby turning owners into tenants is not true as there is no clause in the publicly available texts or committee reports indicating a blanket, automatic conversion of all private freehold titles into leaseholds without process, compensation, or transitional protections. Existing land rates collected by counties under Article 209 remain unchanged and are applied primarily to urban and commercial properties.

The concurrently enacted National Rating Act, 2024 clarifies this by targeting non-agricultural land, exempting rural holdings. Fee adjustments introduced via Legal Notice No. 77 of 2024 relate only to administrative services (registration, transfer, subdivision) reflecting inflationary trends and supporting digitisation.

They are not taxes on ownership. Moreover, the Act empowers the Chief Government Valuer to ensure transparency in valuation, shielding landowners from arbitrary assessments.

The fear of ancestral auction is thus misplaced. Kenya’s Constitution protects the right to property (Article 40) and forbids arbitrary deprivation without compensation. Should any future regulation attempt otherwise, it would immediately invite constitutional challenge. The parliamentary report on NA Bill No. 40 of 2022 (the Land Amendment Bill) shows how targeted and specific many amendments are — they refine procedures, not mass strip ownership.

The difference between administrative reform (registration, gazettement, digitisation) and expropriation is critical and reforms that make tenure clearer and registries more accurate protect owners by diminishing fraudulent disposals and do not, in themselves, convert titles.

Where the Act affects conversions for defined categories (e.g., specific public land redesignations), the Act’s transitional provisions and the Constitution’s due-process protections will govern.

In any case, taxation that effectively deprives property without compensation runs headlong into Article 40. If any regulation attempts that, courts are definitely open to challenge. The proper response to fears of unaffordable administrative costs is advocacy for exemption schedules and county support measures and not categorical claims of immediate dispossession.

Foreign Leases and Sovereignty: Continuity, Not Capitulation

Naituli’s critique of “99-year leases” evokes painful colonial memories, suggesting a return to settler-style entrenchment. Article 65 of the Constitution already limits non-citizen landholdings to leasehold tenures not exceeding 99 years; this is a constitutional ceiling rather than a new concession. The Act clarifies administrative conditions, requires gazettement for public land leases, and strengthens oversight mechanisms to prevent surreptitious alienation.

These features constrain, rather than expand, foreign entrenchment. What the new Act does is refine administrative clarity by standardizing the conversion process for pre-2010 titles, mandates gazettement of all foreign lease approvals, and tightens oversight for “controlled lands” near borders and critical installations.

These are national-security, not neocolonial, measures. Moreover, the Act strengthens conditions for local content, employment, and environmental responsibility in foreign leases. It neither expands foreign rights nor weakens sovereign control; rather, it closes the loopholes that previously enabled elite brokers to mask land grabs through offshore vehicles. In essence, the term length alone does not define sovereignty.

The safeguards that matter is who grants the lease, whether community consent is required (especially for community land), whether national security or border buffers are protected, and whether transparency/compensation regimes apply. The Act tightens these administrative controls.

The claim that the law undermines historical justice.

Another mischaracterisation is that the Act “closes the door” to historical land injustice claims. In truth, it widens it. The committee record and the amendments show a dual tendency: to streamline investigatory timelines (to avoid indefinite limbo) but also to provide enforceable mechanisms and funding for historical redress (indicative budgetary and institutional reinforcements for the NLC and a Restorative Justice Fund in parliamentary discussions).

In some instances, Senate amendments removed rigid cut-offs that threatened to foreclose valid claims. This has enabled continuous reception and investigation of petitions. The National Land Commission’s determinations which were once merely advisory, will now carry enforceable weight upon gazettement, subject to High Court oversight. This shift balances efficiency with access to justice.

The law introduces a Restorative Justice Fund to resource investigations and empowers Parliament to extend inquiry timelines as needed. The objective is not to suppress claims, but to finally resolve them particularly in long-contested zones such as the Coast, Rift Valley, and Lamu Corridor.

Kenya has processed barely 20 percent of historical claims since 2013. The Land (Amendment) Act, 2024 offers renewed momentum, embedding justice within reform rather than beyond it.

In sum, the Act is structured to operationalise historical justice, not close it. The proof is in the committee’s reconciliatory report. The Act, on its face and in committee rationale, appears to expand rather than contract the institutional capacity for redress.

“There was no national conversation—this was stealth legislation.”

The narrative of “stealth legislation” collapses when confronted with the parliamentary record. The Bill was tabled in early 2024, subjected to committee hearings (including NLC and civil-society submissions in February 2024), debated in both Houses, and reconciled through bicameral mediation.

Public participation, mandated by Article 118 of the Constitution, was fulfilled through stakeholder memoranda, livestreamed committee sessions, and published amendments. The law’s assent during a national moment of grief may have muted attention, but not legitimacy. Its journey spanned over a year of deliberation which reflects due process rather than conspiracy.

Conclusion

Land remains Kenya’s most emotive and explosive political issue which is a source of both conflict and cohesion. But reform must not be mistaken for regression. The Land (Amendment) Act, 2024 is not a coup against citizens. If our objective is to safeguard the land rights of ordinary Kenyans, we should be suspicious not of reform but of reform that lacks transparency. The Land (Amendment) Act, 2024 attempts to translate transparency into law in three practical ways:

- Publicly

gazetted notices make allocations and leases discoverable to citizens and

investigators. That reduces the shadow economy of backdoor allocations

that historically dispossessed communities.

- Replacing

paper trails with verified electronic registries (Ardhisasa and related

platforms) curbs fraudulent transfers and creates documentary proof for

smallholders who have historically been easiest to dispossess.

Administrative fee adjustments sustain these platforms; fee policy should

be calibrated with exemptions for vulnerable smallholders. ([Land

Regulations as amended, LN74/2024]).

- The Act’s structural reforms allocate clarity and, crucially, resources to the NLC to investigate historical claims. Without budgets, a mandate is only a moral exhortation; the law ties the mandate to operational mechanisms. The result, if effectively implemented, would be more active redress rather than the long-standing paralysis that has left many communities in limbo.

To resist reform on the basis of misinformation would itself be the true betrayal of the freedom fighters whose cry was not for perpetual suspicion, but for justice. Kenya’s land belongs to those who till it, inherit it, and steward it responsibly under the rule of law. The Constitution envisioned land as a living covenant between people, place, and posterity. The 2024 Act, in its essence, honours that covenant.

The challenge now is not to fight the law, but to use it to demand accountability, defend transparency, and build a future where equity in land is no longer aspiration, but reality. Where genuine abuses/concerns materialise, citizens should use strategic litigation, county political pressure, targeted petitions and mass mobilisation rather than generalized misinformed panic.

Elvis Presley Were is a Lawyer, currently undertaking his articles of pupillage, and works as a Strategic Communications Researcher at Jade Communications Ltd. He is a reader in governance, state accountability and the exercise of public power, with specific interests in Comparative Constitutional Law, Judicial Review and Human Rights.