Forms of unethical practices and corruption encountered in Kenya

What Kenyans said in a survey.

Even though giving and receiving bribes thrive on mutual complicity, public officials hold a position of higher responsibility

In Summary

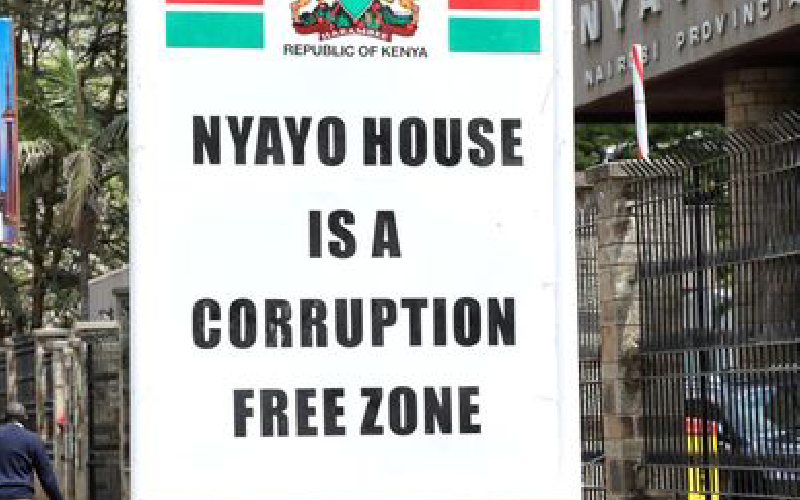

The recently released National Ethics and

Corruption Survey (NECS) 2024 findings by the Ethics and Anti-Corruption

Commission (EACC), revealing that graft cases in Kenya’s public offices involve

giving and taking bribes at 52.1% and 41.9% respectively, paint a grim picture

of a systemic disorder.

While disheartening, these findings are not

surprising in a country where corruption has long been a stumbling block to

fair and equitable development.

They demand urgent reflection and bold

interventions to dismantle the entrenched culture of bribery that threatens to

cripple public service, block progress, and betray the aspirations of the

ordinary Mwananchi.

The fact that over half of the reported corruption cases involve citizens offering bribes highlights a troubling reality.

Many Kenyans feel compelled to pay for services that should otherwise be their right.

Whether it’s securing marriage certificates from the Office of

the Registrar of Marriages, accessing healthcare in public hospitals, or

navigating land transfer processes at land registries across the country, the

expectation of a bribe has become an unwritten law.

On the other hand, cases of public officials

soliciting bribes expose a predatory system where power and public service have

become monetised, and integrity is as rare as a truthful Kenyan politician who

lives up to his colourful and lofty campaign promises after assuming office.

Giving and receiving bribes thrive on mutual

complicity, but the blame should not be equally shared.

Public officials who are entrusted with

serving the public, guided by the Public Officers Ethics Act and code of

conduct, hold a position of authority and responsibility.

When public officers demand or accept bribes,

they enhance a culture of impunity that erodes public trust and normalises

corruption.

Citizens, often desperate and cornered by a

dysfunctional system, may feel they have no choice but to comply.

This dynamic creates a vicious cycle where

both parties are trapped—yet it is Wanjiku, the ordinary Kenyan, not the public

official, who bears the heavier burden of paying out of pocket for the very

services funded by their taxes.

The research findings also raise a deeper

question: why does bribery persist at such alarming levels? Part of the answer

lies in systemic inefficiencies.

Cumbersome bureaucratic processes, low

accountability, and inadequate pay for public servants create fertile ground

for corruption to flourish.

When public offices are underfunded or understaffed,

delays and bottlenecks incentivize ‘speed money’ to expedite services.

Similarly, low salaries for civil servants can

foster a mindset where bribes are seen as a necessary supplement to income, an

unfortunate justification that normalizes extortion.

These structural issues, however, do not

absolve personal responsibility. The culture of bribery reflects a broader

erosion of morality and ethical standards, where self-interest often trumps

public good. To break this cycle, Kenya must adopt a multi-pronged approach.

First, streamlining public services through

digitalization can reduce opportunities for bribery. E-government platforms,

like the e-Citizen portal, have shown promise in minimizing human interaction

in processes like license renewals or permit applications, but there is cause

for worry going by recent reports by the Auditor General, Nancy Gathungu, who

exposed a loss of Sh10 billion illegally collected through the e-Citizen

portal.

Enforcement, too, must be uncompromising. Over

the past few months, EACC has been in the news regularly, arresting and

recommending prosecution of corrupt public officials caught taking bribes,

including traffic police officers, County Government, and Pension officials,

among others.

The strategy by the Commission CEO, Abdi

Mohamud, of tackling corruption at service delivery points is a big relief to

many Kenyans who agonize while seeking services in public offices.

If EACC continues to tackle both petty and

grand corruption in equal measure, then the message that choices have

consequences will be loud and clear to corrupt public officials.

Thirdly, public awareness campaigns can help

shift societal attitudes.

Many Kenyans view bribery as a necessary evil,

but campaigns highlighting its long-term costs, stunted development, unequal

access to services, and eroded trust could foster a collective rejection of the

practice.

Schools, churches, mosques, and community

forums should emphasise integrity as a core value, building a generation that

sees bribery as unacceptable rather than inevitable.

And finally, addressing the root causes

requires tackling economic inequality. Fair wages for public servants, coupled

with merit-based hiring and promotions, can reduce the temptation to solicit

bribes.

Simultaneously, empowering citizens through

better access to education and economic opportunities can lessen the

desperation that drives bribe-giving.

NECS findings are not just a wake-up call;

they present a timely opportunity to end bribery in public service.

By confronting the bribery epidemic head-on,

Kenya can rebuild trust in its institutions and pave the way for a more just

and prosperous society.

The path forward demands courage,

accountability, and a shared commitment to change.

If we fail to act, the cost of corruption will

continue to be borne by the most vulnerable, while the dream of a thriving

Kenya remains just out of reach.

Writer is a Communications Consultant

What Kenyans said in a survey.