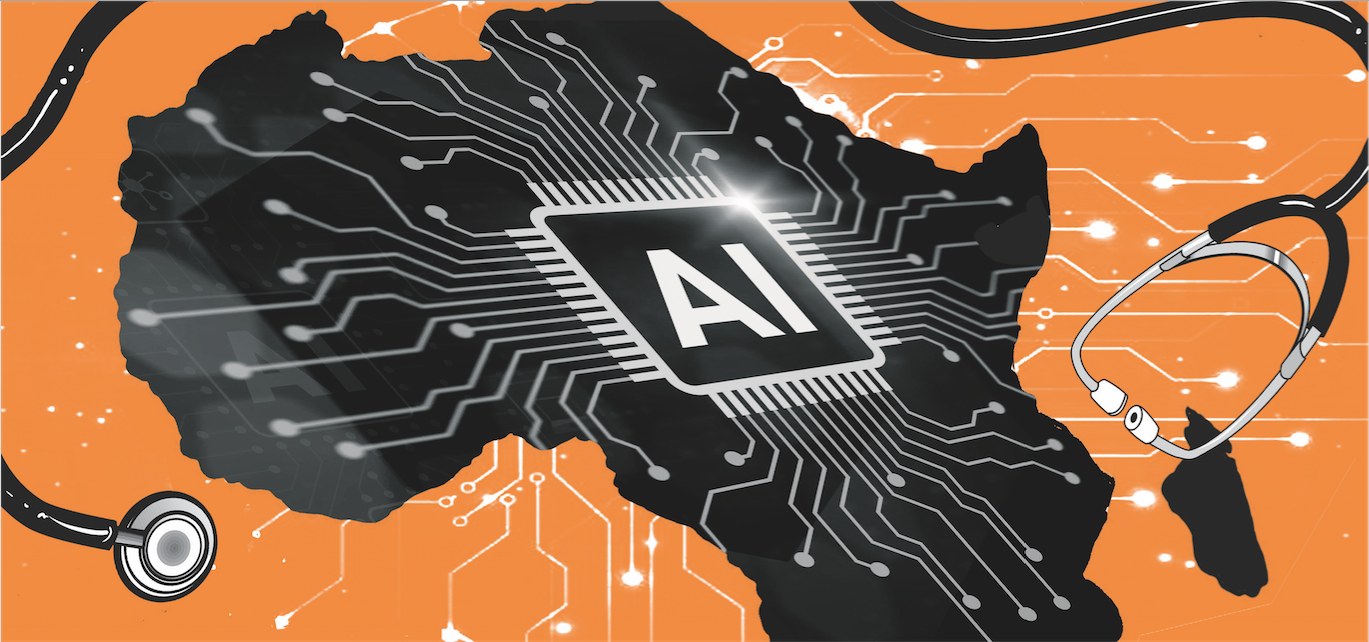

Artificial intelligence dominated nearly every forum I participated in this past week. The settings were varied. There was a conversation at Antler with Emmanuel Lubanzadio, OpenAI’s first Africa Lead. There was Silicon Xchange 2025, where practitioners and investors debated the continent’s digital future. There was Qubit Hub, which explored how innovation arises under constraint.

There was also a workshop at Kenyatta National Hospital on the realities of AI in healthcare. These events did not teach a single unified lesson, but together they sharpened a central question. What kind of AI future should Africa pursue?

A conclusion that has grown clearer to me, reinforced but not dictated by these discussions, is that Africa should not attempt to compete in the global race to build frontier AI models.

These very large systems require capital, energy and research ecosystems that far exceed what most African countries can marshal. This is not a contest the continent can meaningfully enter, and recognising that is not an admission of weakness. It is the beginning of a workable strategy.

Africa’s needs and circumstances differ from those shaping the priorities of frontier laboratories. The greatest potential for AI on the continent lies in solving practical, context-specific problems. These include challenges that rarely appear in global discourse but define daily life in public institutions.

In a Kenyan referral hospital, for example, a single radiologist may interpret hundreds of scans in a day. That workload requires AI designed for rapid triage, consistency under pressure and resilience in unstable environments. A model trained in an entirely different health system cannot be expected to perform well under those demands.

The broader shift in global AI also aligns with Africa’s strengths. Smaller and more efficient models, such as DeepSeek and Phi, show that high capability does not require massive computational infrastructure. These models run on ordinary hardware and perform well on targeted, domain-specific tasks. Efficiency is not a constraint. It is rapidly becoming the new frontier. Africa is well positioned for this direction because it has spent decades building innovation on limited resources.

It is now possible to articulate a coherent strategy rather than a collection of aspirations. Africa’s AI development pathway should unfold in three phases.

The first phase is securing the foundations. This includes African-language datasets, medical datasets and domain expertise governed under national or regional frameworks. Dataset ownership is not only about collection. It requires governance. African institutions must determine how data is stored, who can access it, how consent is managed and how value returns to the public. Without this, data becomes an extractive resource rather than a national asset.

The second phase is targeted deployment in the sectors where AI can deliver transformational value. Healthcare, agriculture, education and public finance are immediate candidates. These areas do not need frontier-scale models. They need tools that understand African environments and can operate reliably within them.

A well-designed maternal health triage system or crop disease detection model would save more lives and generate more economic value than an attempt to replicate a frontier laboratory’s achievement.

The third phase is scaling and export. Once Africa builds AI systems that work in its most demanding environments, those same tools will be relevant to the many regions of the world that face similar constraints.

A radiology assistant who functions dependably in a county hospital in Kenya would be valuable in parts of South Asia and Latin America. This is not only a path to self-sufficiency. It is a path to global contribution.

It is important to clarify what belongs in this strategy and what does not. Africa does not need to build its own version of ChatGPT. That would be a misallocation of scarce resources. However, it does need foundational models that cover African languages and contexts.

Those models are not symbolic. They are infrastructure. The symbolic aspirations are the attempts to replicate frontier-scale efforts rather than build the linguistic and contextual foundations that allow applied AI systems to flourish across the continent.

There is a growing recognition worldwide that the exponential growth in model size cannot continue indefinitely. Energy costs, environmental pressures and diminishing returns are pushing the field toward lightweight, efficient systems. Africa’s long experience with ingenuity under constraint is not a disadvantage. It is a comparative advantage in the next chapter of AI’s evolution.

Africa will not match the financial or computational scale of frontier labs, and it does not need to. The continent can lead in relevance, efficiency and human impact. Leadership will not come from building the largest model. It will come from building the model that makes the most difference.

If Africa chooses the right direction, the next global standard for AI in low-resource healthcare may not emerge from Boston or Beijing, but from a clinic in Nairobi. And that is the kind of leadership the world is ready for. There are already examples of these out there. We need to champion them, yes, but we need many more of them.

Surgeon, writer and advocate of healthcare reform and leadership in Africa