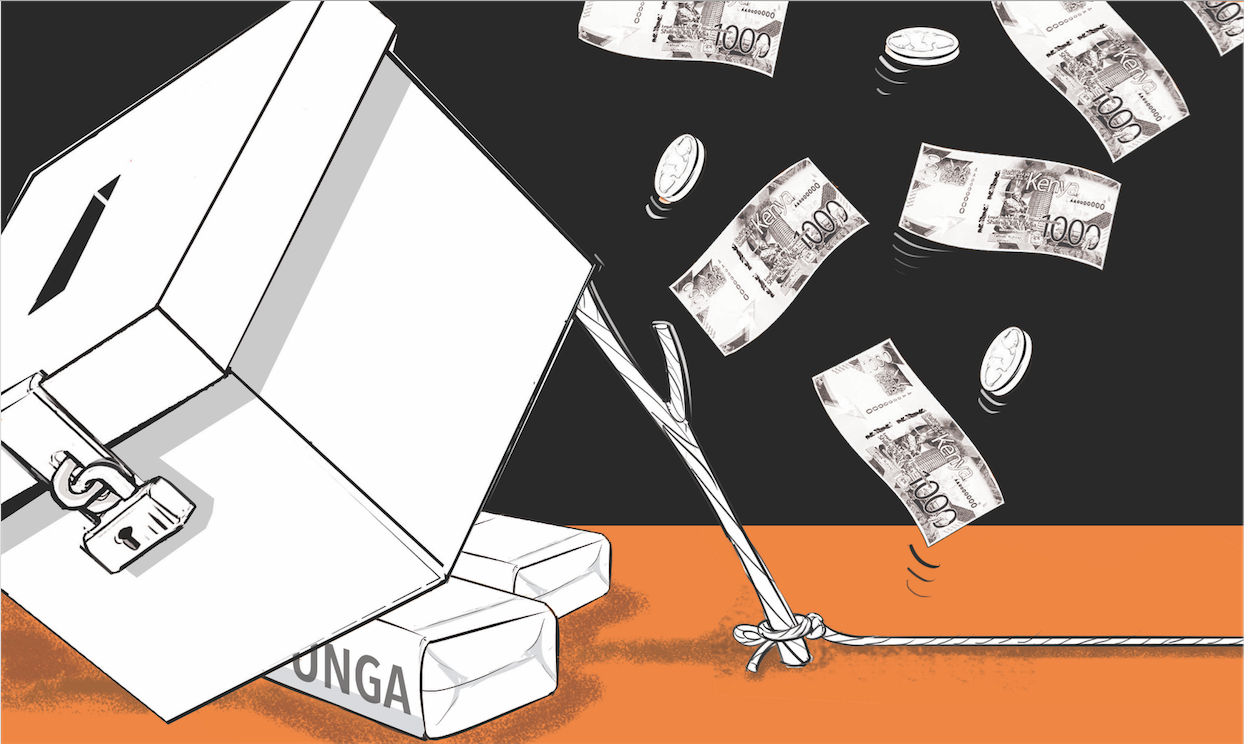

Kenya’s democracy is often lauded as a beacon in East Africa, yet beneath its vibrant electoral contests lies a festering wound: the unchecked flow of money that distorts the playing field. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, constitutionally mandated under Article 88(4)(i) to regulate campaign financing, has spectacularly failed to curb this malaise.

The Election Campaign Financing Act, 2013, tasks the IEBC with setting spending limits, monitoring funds and ensuring transparency—an ambitious remit it has neither the capacity nor the will to fulfil. This failure turns democracy into a marketplace where wealth, not ideas, reigns supreme.

The mandate must be stripped from the IEBC, drawing inspiration from global models that prioritise enforcement over inertia.

The IEBC’s inability to regulate election financing is starkly evident in its track record—or lack thereof. Take the 2022 general election: with 16,106 candidates vying for positions, the commission is silent on the compliance rate by candidates in its 2022 Post-Election Evaluation Report and the Chairman’s remarks.

The report vaguely laments “resource constraints” and “lack of enforcement mechanisms” as excuses, yet offers no data on total spending, donor identities or violations.

This opacity is not new. In its 2017 Post-Election Report, the IEBC similarly noted challenges in “tracking campaign expenditure” due to inadequate staffing and legal gaps, yet failed to produce a standalone report on election financing trends. The absence of such reports—despite the legal mandate—speaks volumes.

This is clear evidence that the IEBC on its own lacks the capacity to enforce the regulations, arbitrate related disputes and conduct elections and their related vagaries, especially during an election year.

The Electoral Integrity Global Report 2023 explored four key contests in 2022: the mid-term elections in the United States, general elections in Kenya and Brazil, and the legislative elections in Hungary. For the general elections, Kenya scored 56 in the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity while Brazil scored 69. The IEBC needs to be relieved of the elections financing mandate so it can strengthen its core elections oversight mandate.

In the 2022 report, it cites “limited resources” and an “overstretched mandate” during election periods, noting that its 1,000+ staff (permanent and temporary) are consumed by voter registration, polling and result transmission. Regulating financing, it argues, is sidelined amid these logistics.

The IEBC had proposed spending caps—Sh4.4 billion for presidential candidates and Sh387 million for governors—but Parliament annulled them in 2021, citing inadequate public participation.

The High Court upheld this in 2022, though it clarified limits do not need parliamentary approval. Rather than refine and reissue rules with broader consultation, the IEBC retreated, leaving the 2022 election a free-for-all. This contrasts sharply with Canada’s Elections Canada, which enforces strict limits (CAD 1,725 per individual donation in 2023) with no parliamentary interference, ensuring compliance through proactive regulation.

The IEBC’s mandate to regulate election financing must be taken away for three compelling reasons.

First, its dual role as election manager and finance regulator creates an inherent conflict. Overseeing polls demands operational focus, sidelining the complex, year-round task of financial oversight—a tension absent in jurisdictions like the UK, where the Electoral Commission focuses solely on regulation.

Second, its consistent failure to enforce laws or produce actionable reports proves it lacks the capacity and credibility to reform itself. In its post 2022 Evaluation Report, the IEBC is “encouraging political parties to support the implementation of Campaign Financing Act”, without providing an enforcement or escalation option.

Third, Kenya’s democracy cannot afford a regulator beholden to political whims with so many key mandate aspects, akin to the best goalkeeper in the world playing solo against a team of 11.

The IEBC’s failure to regulate election financing is a systemic collapse rooted in overreach, incapacity and political capture. Its own reports offer no solutions, leaving Kenya’s democracy vulnerable to plutocracy. The IEBC has had a decade to prove itself; it’s time to stop pretending it ever will.

Social consciousness theorist and author of 'The Gigantomachy of Samaismela' and 'The Trouble with Kenya: McKenzian Blueprint'