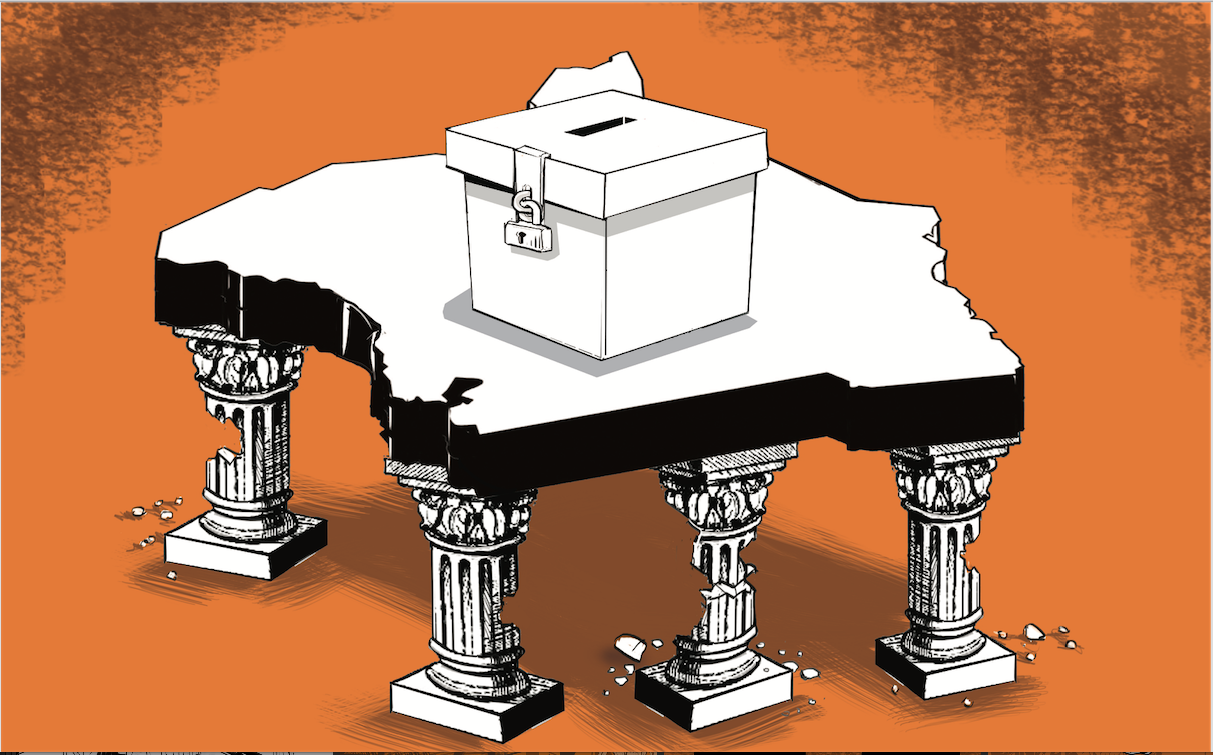

In October 2017, Roselyn Akombe, a former commissioner of Kenya’s Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission, penned a scathing End of Assignment Report that laid bare the institutional rot, political interference and operational chaos that plagued the commission during her tenure from January to October 2017.

Her resignation, announced from New York amid fears for her safety, was a clarion call for reform, warning that the IEBC was “under siege” by partisan interests and internal dysfunction.

As Kenya welcomes a new cohort of IEBC commissioners, namely Erastus Ethekon, Ann Nderitu, Moses Alutalala Mukhwana, Mary Sorobit, Hassan Noor Hassan, Francis Aduol and Fahima Abdallah, Akombe’s report remains a haunting blueprint of the susceptibility areas these appointees must navigate.

With several commissioners linked to political heavyweights in the ruling Kenya Kwanza coalition and the opposition ODM, the question looms: Can they escape the traps that ensnared Akombe’s commission, or are they doomed to repeat history as the 2027 general election approaches?

Akombe’s 92-page report is a masterclass in institutional critique, detailing how the IEBC’s independence was eroded by political intimidation, internal divisions, patronage-driven appointments, procurement scandals and technological vulnerabilities.

Her tenure coincided with the tumultuous 2017 election, marred by the Supreme Court’s annulment of the August presidential poll due to “irregularities and illegalities”. Akombe’s decision to resign, citing the commission’s inability to guarantee a credible repeat election in October, underscored her belief that the IEBC had become a pawn in Kenya’s polarised political chess game.

Her report identified five key susceptibility areas: Institutional issues, election operations, electoral technology, public outreach and legal reforms. Collectively, they continue to threaten the IEBC’s integrity.

For the new commissioners, these areas are not just historical lessons but active minefields, exacerbated by their own political affiliations.

Akombe’s most damning revelation was the pervasive political interference that turned IEBC plenary meetings into battlegrounds of fear and intimidation. She recounts how government and party officials received “blow-by-blow briefings” of closed-door discussions, with commissioners facing calls from political actors after meetings.

This created a chilling effect, where some commissioners remained silent or aligned with “reporters” to avoid retribution. The new commissioners, several of whom have ties to Kenya’s political elite, are particularly vulnerable to this pressure.

Akombe’s report vividly describes the IEBC’s internal dysfunction, driven by dual centres of power between the chairperson and the CEO, which fractured the commission into factions. This was starkly evident when five commissioners publicly disavowed chairman Wafula Chebukati’s memo to the CEO in September 2017, undermining staff morale and exposing the commission’s disunity. Political actors exploited these divisions, pitting factions against each other to advance their agendas.

The new commissioners face a similar risk, particularly given their political affiliations.

Akombe criticised the IEBC’s appointment process, noting that commissioners were selected through political deals rather than expertise or integrity.

The 2017 commission, including herself, lacked election management experience, making it reliant on a politically influenced secretariat. This patronage tied commissioners to the executive, undermining their independence and exposing them to accusations of bias.

Procurement irregularities were a recurring theme in Akombe’s report, with processes for the Kenya Integrated Electoral Management System and ballot papers mired in “intrigue” and allegations of corruption, which dubbed the 'Ballot paper saga'. She describes tender evaluation committees as “harvest season” for personal gain, recommending an independent audit of procurement from 2012 to 2017.

The new commissioners join IEBC when the secretariat has already submitted the current financial year’s budget to Parliament. They will be sitting ducks for vote lines already pre-determined.

Akombe’s report is not just a critique but a roadmap for reform. If the new commissioners fail, the cost will be another election mired in controversy, further eroding public trust in the democratic process.

The writer is a Social consciousness theorist & author of 'The Gigantomachy of Samaismela' and 'The Trouble with Kenya: McKenzian Blueprint'