He sees potential. Potential in the young people eager to learn, in the local economy hungry for skills, and in the community that once had limited access to structured hospitality education.

“Naivasha is booming in tourism,” he says, gesturing toward the green hills that surround the campus.

“But there was no structured hospitality training institution here. Young people have had to travel to Nairobi or Mombasa to study these courses. We want to change that.”

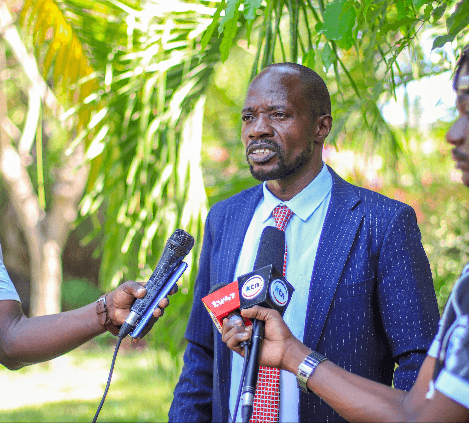

Lenaiyarra, the centre manager at MTCC, is at the forefront of a bold initiative that is reshaping how hospitality training is delivered in the region.

At first glance, one might not expect this kind of transformation to be led by a company better known for transporting fuel than serving food.

But through the Kenya Pipeline Company (KPC)’s education and conferencing arm, the Morendat Institute of Oil and Gas (MIOG), a powerful convergence between infrastructure and impact is quietly taking place.

Located just 12km from Naivasha town, the MTCC was originally constructed in 2008 as a residential estate for KPC staff. Over time, it grew into a multipurpose hub offering training, conferencing and accommodation.

With its six conference halls, 56 guest rooms, a fully equipped kitchen, gym, sauna and swimming pool, MTCC was already a standout facility in the region.

But even with these resources, Lenaiyarra and his team saw a deeper need, one not yet addressed.

“We noticed a gap,” he says. “There was no local institution offering professional training in hospitality. Hotels were growing but the workforce wasn’t keeping up.”

The region’s popularity as a conference and tourism destination had outpaced its training capacity.

According to the Kenya Tourism Research Institute, Naivasha accounts for nearly 60 per cent of conference tourism in the Rift Valley.

Meanwhile, Nakuru county's hospitality sector had seen hotel bed capacity grow by 35 per cent between 2018 and 2023, while employment in the sector grew by 28 per cent.

“The numbers were telling,” Lenaiyarra recalls. “There was a huge demand, but no supply of skilled professionals from within the area.”

BRINGING TRAINING CLOSER

To bridge this gap, KPC is launching a new hospitality training programme through MIOG, starting in September 2025.

This isn’t just any short-term fix; it’s a full-fledged training school, offering certificate and diploma courses in culinary arts, food and beverage service, housekeeping and general hotel operations.

The first intake will consist of 40 students — 20 in culinary arts and 20 in general hospitality. And it’s not just about numbers; it’s about inclusion.

“In each course, we’ve reserved three full scholarships for students from Naivasha,” Lenaiyarra says. “This is part of our commitment to giving back to the local community.”

The programme is offered in partnership with the Boma Institute of Hospitality and will run under MIOG, which has recently been elevated to a national polytechnic status by the Kenya Universities and Colleges Central Placement Service (Kuccps). This milestone allows students to apply through government placement systems, increasing visibility and access.

Certificate courses will span one year, while diploma programmes will take two. Short, professional courses tailored to specific industry needs are also in the pipeline.

LEARNING BY DOING

What makes this programme stand out is its practical, hands-on approach. MTCC is not just a training school, it’s a fully operational hospitality facility.

Every guest room becomes a training ground for housekeeping students. The professional kitchen doubles as a culinary lab. The conference halls and restaurant serve as living classrooms.

“There’s no need to build from scratch. We already have what we need to deliver practical lessons,” Lenaiyarra says. “Our students won’t just read about hospitality, they’ll live it every day.”

This integrated approach ensures that students graduate with both academic knowledge and real-world experience, making them highly employable in a competitive market.

In a region dominated by high-end lodges and privately owned resorts, MTCC could have chosen to compete on luxury. Instead, it’s carving out a new niche: hospitality with a purpose.

“Our goal is not to compete purely on luxury but on value and skills,” Lenaiyarra says. “We want organisations to know that when they book our facilities, they are also supporting a learning institution.”

This social enterprise model ensures that income from conferencing and accommodation is reinvested into the training programmes, creating a self-sustaining cycle of education and empowerment.

“About 95 per cent of our business is conferencing,” he adds. “Only 5 per cent is leisure. Our facilities meet the expectations of our clients, while supporting our broader education goals.”

Clients include government agencies, non-profits, universities and private firms.

With conference room capacities ranging from 25 to 250 participants and amenities like a gym, sauna and team-building grounds, MTCC is increasingly seen as a one-stop-shop for training retreats.

MTCC’s success isn't measured only in revenue or guest counts. It’s also measured in lives changed. Local youth, who once had no access to structured hospitality training, now have a path to meaningful careers.

Parents who couldn’t afford to send their children to Mombasa or Nairobi can now see them thrive closer to home.

Moreover, MTCC employs locals in various roles, from housekeeping to groundskeeping. Through the KPC Foundation, a portion of its earnings is channelled into community projects, such as building classrooms, improving dispensaries and supporting local schools.

“We believe in uplifting where we operate,” Lenaiyarra says. “It’s not just about running a centre. It’s about being part of the community.”

NEW NARRATIVE

MTCC’s evolution from a staff estate to a national hospitality training hub is a compelling example of how state-owned enterprises can redefine their impact.

While KPC’s core mandate remains energy infrastructure, it is increasingly leveraging its assets to support national development goals, particularly in youth empowerment, skills development and community engagement.

“Many people don’t associate KPC with hospitality or training,” Lenaiyarra admits.

“We’re working on marketing and building awareness that MIOG is also about skills, not just in oil and gas but now in hospitality, too.”

It’s a challenge but also an opportunity to rewrite public perception and showcase what’s possible when state corporations think beyond pipelines and profits.

Looking ahead, there’s cautious optimism. If the first intake proves successful, MIOG could replicate the model across other campuses, creating a network of hospitality training centres around the country.

There are still hurdles to overcome, chief among them visibility and sustained funding, but the groundwork has been laid. And with champions like Lenaiyarra leading the charge, the future looks promising.

“Our procurement process is transparent and our standards are high,” he says. “That gives us an edge, especially with public institutions.”

As Kenya grapples with youth unemployment and skills mismatch, initiatives like the MTCC hospitality school offer more than training, they offer hope.

Hope that learning can be accessible, that institutions can evolve and that communities can be transformed from the inside out.

What started as a petroleum project is today nurturing dreams far beyond energy. Through MTCC, KPC is not just building pipelines, it is building futures.