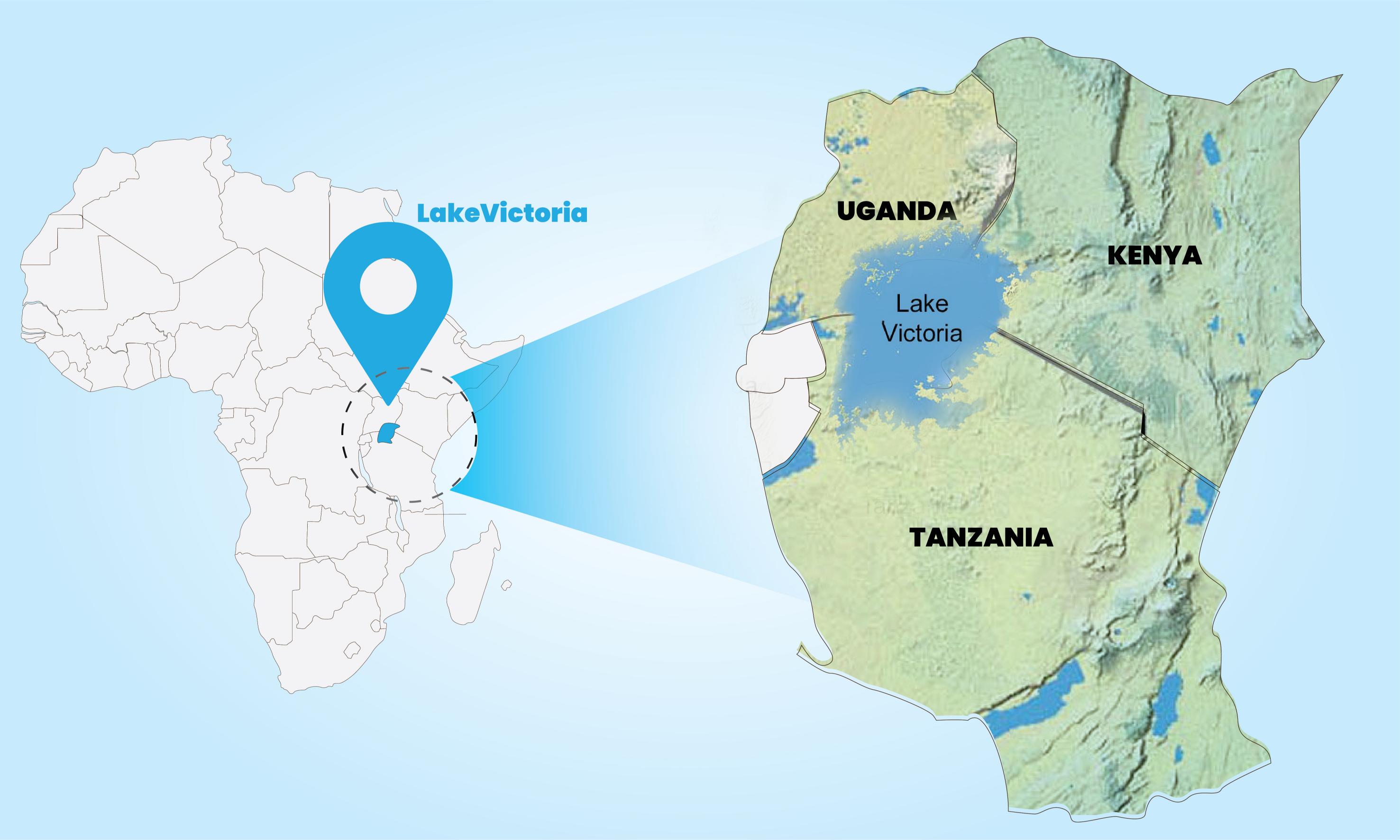

But increasingly, its waters have become a flashpoint, with frequent border arrests, seized boats and accusations of illegal fishing now routine on the lake shared by Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania.

To ease tensions, the three nations are advancing a long-sought-after plan to establish a unified fishing licence, potentially reshaping governance on one of Africa’s most vital water bodies.

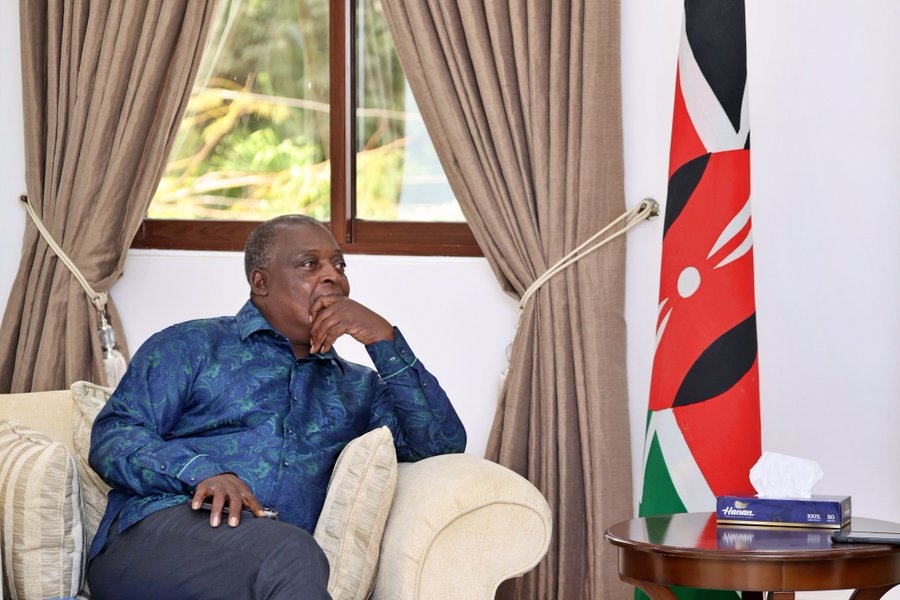

Last week, President William Ruto said he had sent emissaries, led by Mining CS Hassan Joho, to engage Ugandan and Tanzanian officials in a bid to resolve the maritime border dispute once and for all.

“There is currently a conversation going on between our three countries so we can find a way to have a uniform licence for all our fishermen, to avoid this country arresting that country’s people and the rest of what is going on at the moment,” he said during his ongoing tour of lakeside Kenya.

A unified regulatory framework would grant fishers from all three countries a single, mutually recognised permit.

The proposed joint licence would thus allow verified fishers from any of the aforementioned states to access the lake freely, subject to agreed-upon rules.

It would also formalise monitoring and data-sharing mechanisms, enabling the three governments to better track fish stocks, tackle illegal fishing and harmonise enforcement.

Proponents argue this would not only de-escalate cross-border tensions but also introduce much-needed order to a lake whose resources are under increasing strain from overfishing, pollution and climate change.

The ongoing talks are also expected to address the lingering diplomatic standoff between Kenya and Uganda concerning fishing rights around Migingo Island, an enduring flashpoint often dubbed Africa’s ‘smallest war.’

BONE OF CONTENTION

Fish-rich, Migingo Island is a rocky outcrop in Lake Victoria, spanning just 2,000 square meters (0.49 acres). Smaller than a football field, it is crammed with corrugated metal shacks and has some 500 residents, mostly fishermen.

In 2009, the dispute nearly triggered a violent clash between Ugandan and Kenyan armed forces, as Ugandan police raised their flag on the island and imposed fishing permits on Kenyan fishermen, sparking diplomatic outrage.

While occasional diplomatic negotiations have helped defuse tensions, the absence of a structured policy has meant persistent disputes, with frequent arrests and detentions further complicating regional relations.

Lake Victoria, the world’s second-largest freshwater lake by surface area, spans some 68,800 square kilometres and supports more than 40 million people living in its basin.

At its heart is a fishing industry valued at more than $500-$800 million annually, dominated by the prized Nile perch and tilapia, according to the African Great Lakes Information Platform.

The lake supplies more than one million tonnes of fish each year, according to the Lake Victoria Fisheries Organisation, and is central to regional food security, employment and export revenue.

However, the benefits have been undermined by a patchwork of national regulations, overlapping jurisdictions and dwindling fish stocks.

Fishers who drift across invisible aquatic borders are often met with arrest or the confiscation of gear. In some cases, violence has flared.

A Ugandan fisherman operating near Kenyan waters, for instance, may unknowingly or intentionally breach Kenya's exclusive fishing zone, an act that could cost him his boat or his freedom.

Local media frequently report on fishers held for weeks or even months, and community resentment is rising.

“The lake doesn’t know borders,” says Dr Margaret Achieng, a fisheries expert based in Kisumu.

“But our governance of it has been territorial, politicised and outdated. What we’re seeing now is a step towards rationality.”

FISH DECLINING

Experts hope the move will lead to a wider ecosystem management approach rather than reactive policing.

Still, questions remain about how revenue from licence fees would be shared, how enforcement would be carried out jointly and what mechanisms would be used to resolve disputes.

Previous attempts at regional cooperation, such as the Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project — established in 1994 — have achieved mixed results due to political mistrust and inconsistent implementation.

Meanwhile, fish stocks in Lake Victoria have declined sharply over the past two decades. The Nile perch population, once booming, has dropped drastically in some parts of the lake, according to research by the National Fisheries Resources Research Institute in Uganda.

Overfishing, pollution and the use of illegal gear have worsened the crisis with the economic fallout already being felt.

In Kenya, 2024 data from the Central Bank of Kenya showed that fish export earnings declined by 12.07 per cent in 2023, falling from Sh6.67 billion to Sh5.86 billion.

The Sh805.29 million drop marked the first major downturn since 2020, when revenues fell by Sh681.61 million.

Meanwhile, Kenya’s fish production from Lake Victoria shrank to 70,300 tonnes in 2023, down from 86,400 tonnes in 2022, according to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics.

Many stakeholders believe the joint licence could set a precedent for deeper regional integration in natural resource management.