AI Illustration

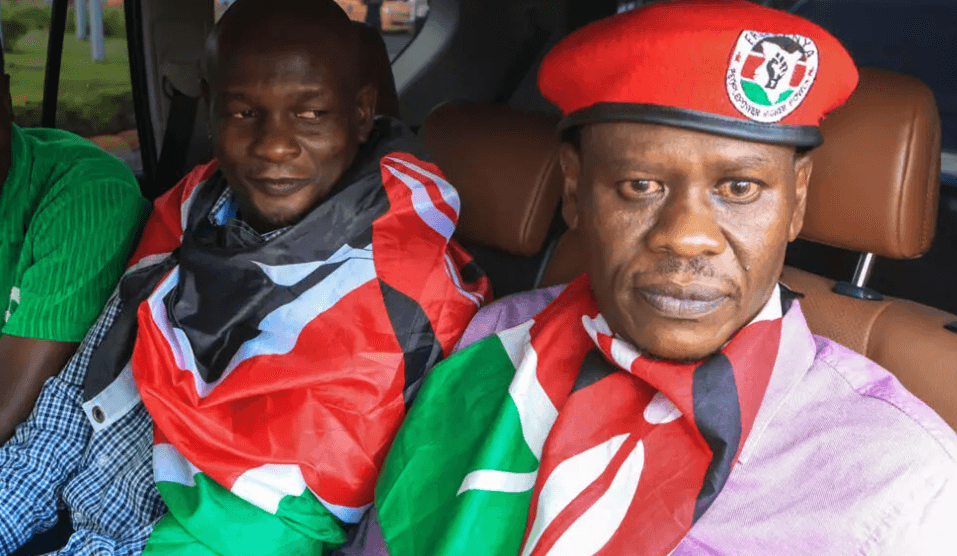

AI IllustrationThe recent high-profile deportation of foreign nationals

from Kenya has thrust the intricate legal framework surrounding immigration and

removal into the national spotlight.

While Kenya is a welcoming nation, its sovereignty dictates

a clear set of circumstances under which non-citizens can be deemed undesirable

and removed from its borders.

Understanding these legal provisions, both domestic and

international, is crucial for foreign residents and authorities alike.

The primary legal instrument governing immigration and

deportation in Kenya is the Kenya Citizenship and Immigration Act, No. 12 of

2011.

This comprehensive piece of legislation outlines various

grounds for an individual’s removal, emphasizing the importance of legal entry,

valid documentation, and adherence to Kenyan law.

Grounds for deportation

One of the most common reasons for deportation is unlawful

presence. This includes individuals who entered Kenya without a valid visa or

permit, overstayed their authorized period of stay, or failed to renew their

documentation.

Section 34 of the Act clearly states that "a person who

is in Kenya without a valid permit or pass" is liable to be removed.

Criminal offenses are another significant trigger for

deportation. Any non-citizen convicted of an offense punishable by

imprisonment, regardless of the length of sentence, can be declared a

prohibited immigrant.

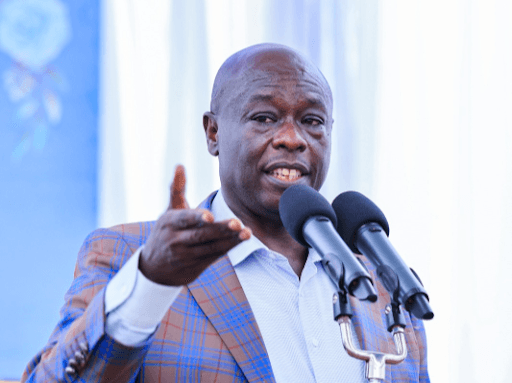

The Act grants the Cabinet Secretary for Interior and

National Administration the power to declare a person a prohibited immigrant if

they have been convicted in Kenya or in any other country of an offence

specified in the Schedule, or of an offence for which a sentence of

imprisonment has been passed.

This extends to serious crimes such as terrorism, drug

trafficking, human trafficking, and financial fraud.

Even if an individual has served their sentence, the

conviction itself can be grounds for removal.

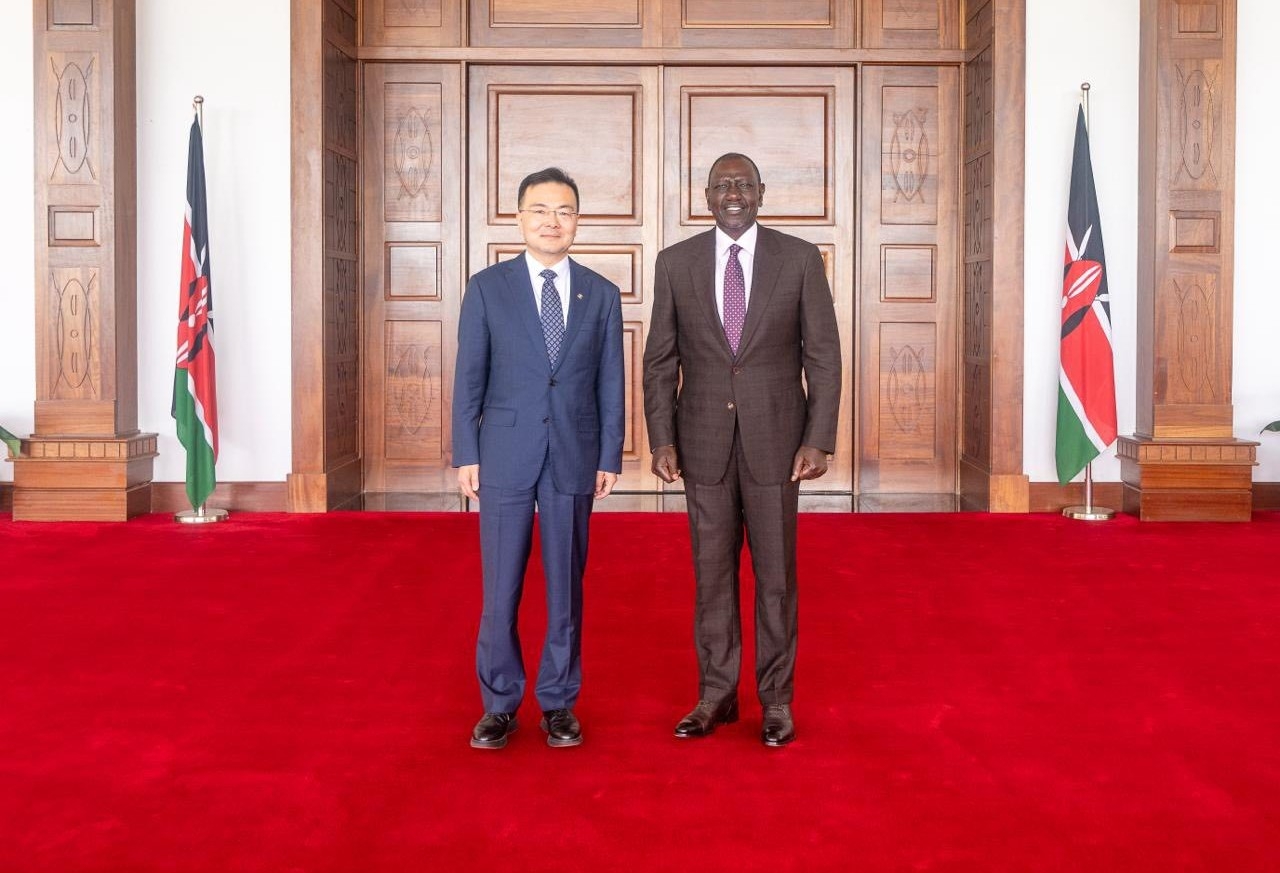

Furthermore, individuals deemed to be a threat to national

security or public order are also subject to deportation.

Section 36 of the Act allows for the removal of a person

whose presence "is or would be contrary to national interest."

This broad clause provides the government with discretion in

cases where an individual's activities, even if not directly criminal, are

perceived to undermine the peace and stability of the nation.

This can include individuals involved in radicalization,

espionage, or inciting public unrest.

Breach of immigration terms and conditions can also lead to

deportation. For instance, a foreign national holding a work permit for a

specific role who is found engaging in unauthorized employment or violating the

conditions of their permit can face removal.

Similarly, those who obtain their permits through fraudulent

means, such as providing false information or documents, are also liable for

deportation once the deception is uncovered.

The Act also outlines a process for appeals and

representations against a deportation order. However, these processes are often

complex and time-sensitive, requiring prompt legal intervention.

International Law

While national sovereignty grants states the right to

control their borders, international law provides a framework and certain

limitations on deportation.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), though not

legally binding, asserts in Article 13 that "Everyone has the right to

freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each state."

However, this right is generally understood to apply to

citizens, and states retain the right to regulate the entry and residence of

non-citizens.

More pertinent are conventions related to refugees and

stateless persons.

The 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol, to which

Kenya is a signatory, prohibit the expulsion or return

("refoulement") of a refugee to a country where their life or freedom

would be threatened on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership

of a particular social group, or political opinion.

This principle of non-refoulement is a cornerstone of

international refugee law, meaning that even if a refugee has committed a

crime, they cannot be deported to a place where they face persecution.

Similarly, international human rights law, as enshrined in

instruments like the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(ICCPR), places restrictions on arbitrary deprivation of liberty and ensures

due process in deportation proceedings.

Article 13 of the ICCPR states that an alien lawfully in the

territory of a State Party may only be expelled in pursuance of a decision

reached in accordance with law and shall, save where compelling reasons of

national security otherwise require, be allowed to submit the reasons against

his expulsion.

The principle of family unity is also a consideration in

some international legal frameworks, particularly when deportation would

separate families.

While not an absolute bar to deportation, it can be a factor

taken into account by judicial bodies.

Deportation process

The deportation process in Kenya typically begins with the

issuance of a "Notice of Intention to Declare a Prohibited Immigrant"

or a "Deportation Order."

This order is usually issued by the Cabinet Secretary for

Interior and National Administration or an authorized immigration officer.

The individual is then given an opportunity to make

representations against the order.

If these representations are deemed insufficient, the

deportation order is executed, often with the individual being escorted to the

nearest port of exit.

In some cases, especially those involving national security,

the process can be expedited, and individuals may be detained pending

deportation.

The government often works in conjunction with the embassies

or high commissions of the individuals concerned to facilitate their removal.