Admission by Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni that his government detained two Kenyan activists has stirred debate over what international law says about treatment of foreigners during arrest and detention.

The two activists, Bob Njagi and Nicholas Oyoo, were released after more than a month in custody.

Their detention had been shrouded in uncertainty until Museveni confirmed they had been arrested and accused of working with opposition groups seeking to unseat him in the January general election.

The pair disappeared on October 1 shortly after attending a rally by Museveni’s main challenger, the popular musician-turned-politician Bobi Wine.

The Uganda government initially denied any involvement.

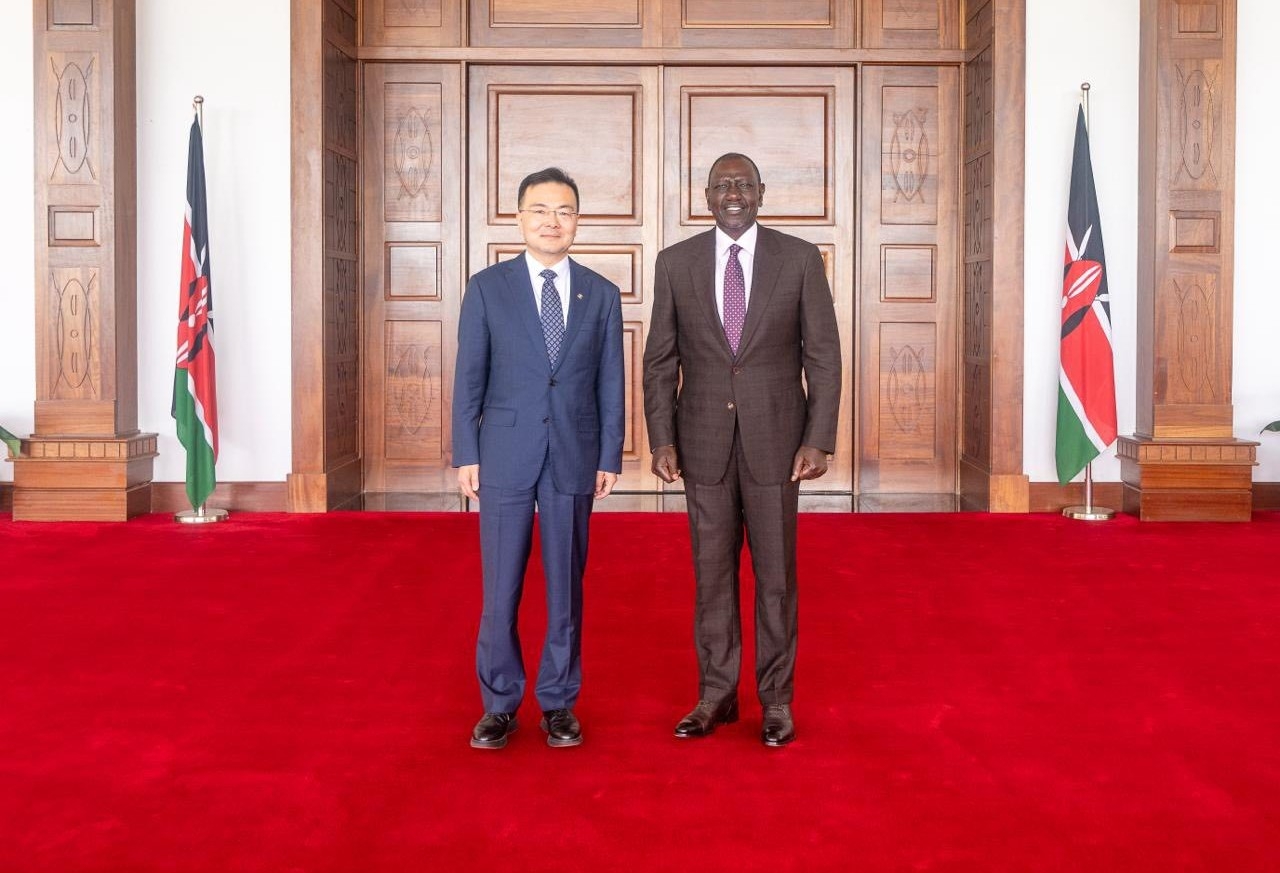

Prime Cabinet Secretary Musalia Mudavadi said the two men were released to the Kenyan ambassador after weeks of what he described as open and constructive communication.

Njagi and Oyoo returned to Kenya on Saturday and said they had been held in a military facility guarded by Ugandan special forces under what they termed inhumane conditions. They did not give further details.

Their case has raised fresh questions about what international law permits when foreign citizens are detained, and what protections individuals are entitled to when held outside their home country.

“International human rights law has evolved to insist on safeguards. Administrative detention without charge cannot be indefinite, must be regularly reviewed, and must respect basic rights,” an international law expert said.

International law provides a clear framework; detention must never be arbitrary, must follow established legal procedures, and must respect fundamental human rights.

Experts point first to the universal right to liberty and security of person, which applies to everyone regardless of nationality.

This right is set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

Article 9 of the ICCPR states, “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention” and adds that “No one shall be deprived of liberty except on grounds and procedures established by law.”

Immigration detention is one of the most common areas where international law guidance is applied.

It is widely accepted, including in European Union practice, that detention of non-nationals should be an exceptional measure.

Authorities must first consider less restrictive alternatives such as reporting obligations, financial guarantees, or designated residence arrangements. Detention cannot be used simply to deter irregular migration or to punish someone for political activity.

Detention is considered arbitrary when it is unreasonable, unjust, or disproportionate in the circumstances. Indefinite detention is almost always deemed arbitrary.

International bodies have repeatedly stressed that the length of detention must be closely tied to a legitimate purpose, and that authorities must act with due diligence at all times.

Foreign nationals in detention enjoy specific procedural rights from the moment they are deprived of their liberty.

These include access to a lawyer and free legal assistance if needed, access to a medical doctor, the right to notify a relative or another third party, and the right to challenge the lawfulness of detention before a court.

If the detained person does not understand the local language, they have the right to an interpreter.

The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations strengthens these protections.

It requires detaining authorities to inform foreign nationals of their right to have their consulate notified.

This right belongs to the detainee, not the state, which means individuals can choose whether or not the consulate is contacted.

Consular officials are allowed to visit detained nationals and help ensure their rights are respected.

Certain groups receive heightened protections. Children should generally not be detained for immigration or administrative reasons.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child views such detention as contrary to a child’s best interests.

Stateless persons and those with disabilities are also considered particularly vulnerable and should only be detained in very rare cases.

The legal landscape becomes more complex when detention occurs in the context of armed conflict.

Both international humanitarian law (IHL) and international human rights law (IHRL) apply.

The Third Geneva Convention outlines detailed protections for prisoners of war, while the Fourth Geneva Convention sets rules for the detention of civilians.

These rules include humane treatment, prohibition of torture, and respect for personal dignity.

In non-international armed conflicts, IHL provides fewer details, although core guarantees remain.

Detained persons must not be subjected to violence, murder, rape, cruel treatment, or humiliation.

Arbitrary deprivation of liberty is prohibited. These guarantees apply at all times.

One of the most controversial practices is administrative detention, also known as internment.

This allows governments to detain individuals considered security threats even when there is no specific criminal charge.

While IHL recognises this type of detention during armed conflict, developments in human rights law have placed limits on the practice.

The case of Njagi and Oyoo has renewed attention on these rules.

Human rights observers say the secrecy surrounding their detention raises concerns.

Uganda’s initial denial, the activists’ claim of military detention, and their allegations of inhumane treatment highlight the gaps that often appear when political tensions spill into cross-border arrests.

Legal analysts argue that the incident underscores the need for states to uphold international obligations even in politically charged situations.