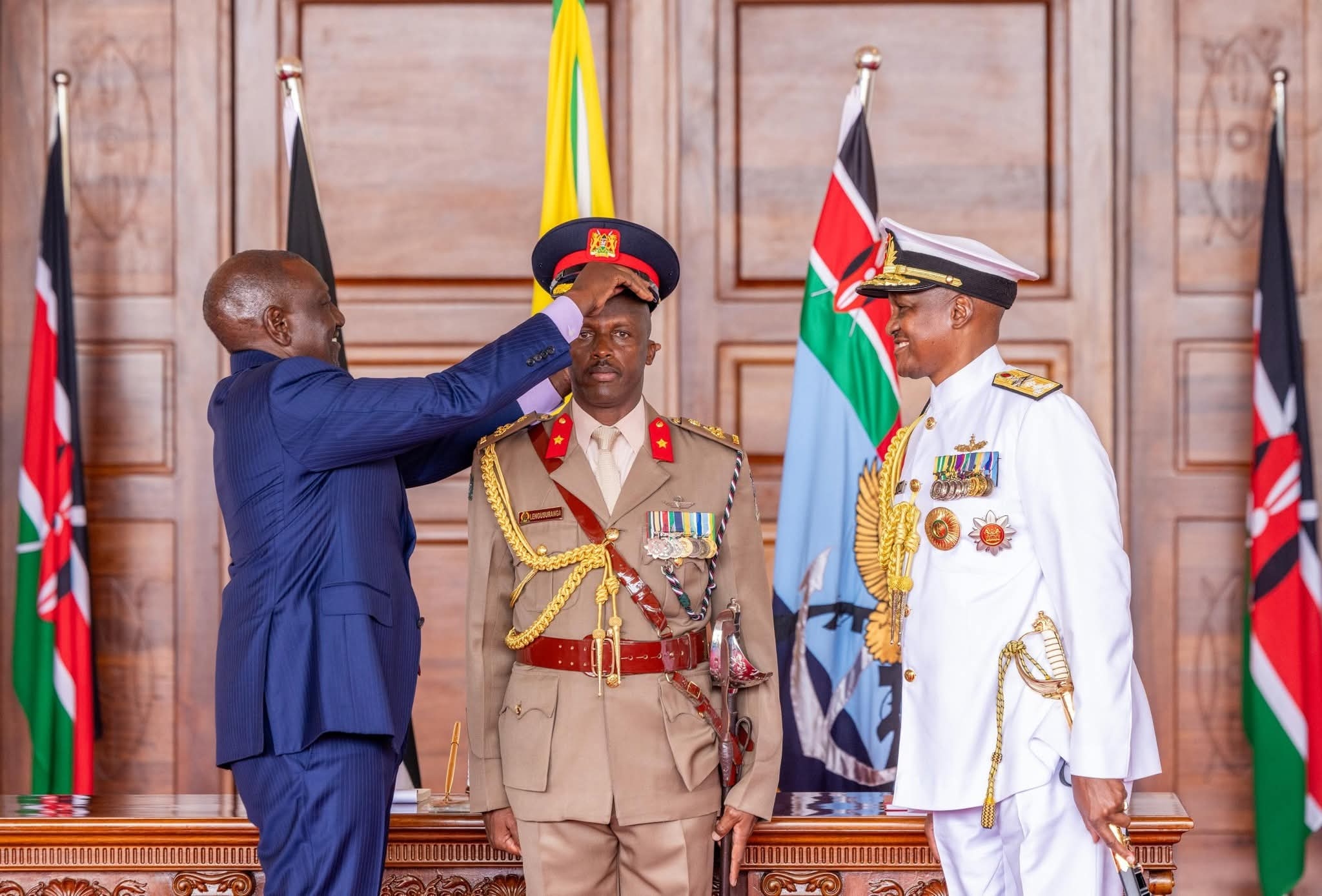

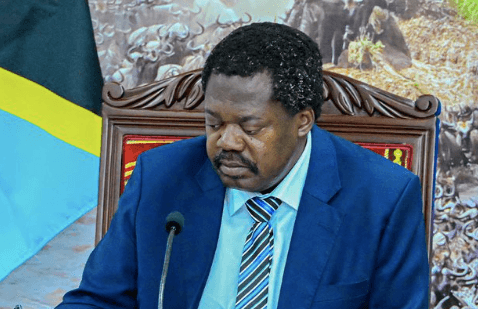

Dr Josephine Kibaru-Mbae, the former Director-General of the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD).

Dr Josephine Kibaru-Mbae, the former Director-General of the National Council for Population and Development (NCPD).

For many Kenyan women, fear and stigma remain the key barriers to breast cancer screening. A new study suggests that few people talk openly about the disease and even fewer about being examined.

The result is late diagnosis, leading to poor treatment outcomes.

Dr Josephine Kibaru-Mbae, an obstetrician-gynaecologist and former director general of the National Council for Population and Development, considers herself lucky.

She had a mammogram in 2020, which did not find any problems in her breasts.

She was therefore not worried when, in May 2022, she noted a small lump in her left breast.

But she still took caution.

“So I went for another mammogram and ultrasound and a subsequent needle biopsy. I waited for 14 days for the results, suffice to say those were the longest days of my life,” she explains.

The results were positive for breast cancer and the journey commenced. She went through chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy and immunotherapy and is now on long-term hormonal therapy.

Kibaru said she chose to speak out to help others overcome fear and stigma.

“I have not been very vocal in advocacy, partially because I recognise the stigma attached to being diagnosed with cancer. There are many medics suffering in silence with all kinds of illnesses including mental health, but we find it difficult to share our stories, I believe in part due to our training to take care of others. But I want to tell my fellow medics, it is alright to let others take care of us, we also deserve care,” she said.

Her openness has sparked a wider conversation about why screening uptake remains so low in Kenya and why silence is costing lives.

A study published in the Plos One journal in April found only 13.91 per cent of women aged 15-49 have ever undergone a clinical breast examination by a health professional.

Women with higher media exposure were more likely to get screened.

“Our study found that women residing in communities with a higher proportion of media exposure exhibited significantly greater uptake of Clinical Breast Cancer Screening Uptake (CBCSU) than those in communities with limited media exposure,” says the study, titled ‘Clinical breast cancer screening uptake and associated factors among reproductive-age women in Kenya’.

Breast cancer remains Kenya’s most common cancer among women.

The National Cancer Institute says the annual incidence of breast cancer in Kenya is approximately 6,799 new cases, representing around 16.1 per cent of all new cancer cases.

Kenya’s National Cancer Screening and Early Diagnosis Action Plan already outlines steps to improve early detection, but implementation remains uneven.

Many public hospitals lack the personnel and facilities to offer routine breast examinations and few counties have sustainable outreach programmes targeting women with low media exposure.

Early detection dramatically improves survival, but treatment options are limited and costly when one is diagnosed late. About 3,000 women die of breast cancer in the country every year, mainly due to late diagnosis.

The Plos One study also identified age, education and income as major determinants of screening.

Women with “primary education and those with secondary or higher education had higher odds of clinical breast cancer screening uptake”.

Wealth also made a difference because women in the richest households were 2.19 times more likely to have been screened than those from poorer families.

Information exposure emerged as one of the most powerful enablers, which means women who regularly encounter health information through radio, TV, or social media are more likely to seek screening.

The findings mirror what Kibaru-Mbae experienced firsthand: awareness, education and support networks make the difference between early action and delay.

“How does that lady in Kibera or Kiandutu slums cope with all the nutritional and medical needs related to managing this disease?” she asked.

The doctor advises that women should not ignore breast changes, should get professional examinations and seek emotional support.

She also urges fellow health workers to prioritise their own wellbeing and undergo regular check-ups despite social expectations that they must always be caregivers.