Community elder Peter Leisido and Pacidas project manager Hokile Boku

next to a pit latrine /DENIS GATUMA

Community elder Peter Leisido and Pacidas project manager Hokile Boku

next to a pit latrine /DENIS GATUMA

As we drive through Soito village in Marsabit county, a group of excited children runs alongside us, waving and shouting in their local dialect.

“Do you want to see the toilets?” they ask, pointing towards the manyattas scattered across the field. In this community, also known as Lorokushu, pit latrines have become a source of pride.

Every homestead now either has a completed latrine or one under construction, a sign of the village’s transformation.

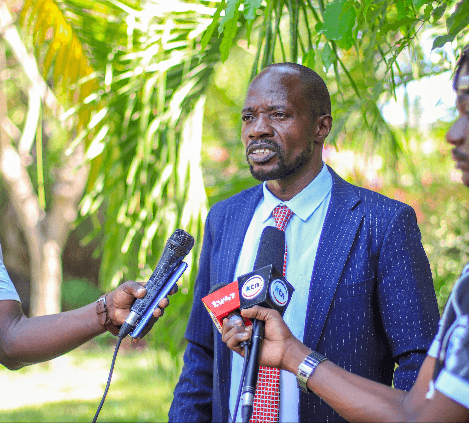

Leading us through this change is Peter Leisido, an elder coordinating the project in Lorukushu, which has more than 65 households. So far, 25 latrines have been built.

“Each family committed to building a latrine just a few metres from their home. We’ve also encouraged everyone to set up a hand-washing station outside the latrine, usually a two or three-litre jerrycan filled with clean water,” he said.

For women like Celina Letore, the transformation has been life-changing.

“We used to relieve ourselves in the bushes. It was dangerous, especially at night as we risked snake bites or attacks from wild animals. But now, we feel safer,” she said.

According to the 2019 Kenya Population and Housing Census, Marsabit and Samburu are among 15 counties where 85 per cent of open defecation occurs.

During the rainy season, human waste gets washed into water sources used for drinking and cooking, increasing the risk of diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera and stomach infections.

“Since building the latrines, we’ve seen fewer cases of stomach illnesses, especially among children and the elderly,” Letore said.

Nationally, more than 6,600 children under five die annually from diarrhoea and 80 per cent of those cases are linked to poor sanitation, hygiene and unsafe water.

“When we first arrived, we asked, why are there no toilets? We learnt that no one had explained the importance of having a latrine. Our first task was to change that mindset,” Hokile Boku, the project manager said.

With funding support from the Australia’s Department for Foreign Affairs and Trade through Oxfam Kenya, Pastoralist Community Initiative and Development Assistance rolled out a hygiene and sanitation programme to improve public health in Arid and Semi-Arid Lands in Soito and seven other villages.

The initiative follows the Community-Led Total Sanitation model (CLTS), urging households to build latrines using locally available materials such as timber, tree branches, clothes and ashes.

Training sessions were delivered in partnership with community health promoters, community health workers and public health officers. “We learnt how to dig a proper pit, use cement for the base and timber for a secure structure,” Leisido said.

Not all change came easily. “Some elders believed the latrines were a symbol of graves s. But after sensitisation on health benefits, many embraced the idea.

Today, those same elders are now champions of sanitation awareness. The cultural shift has been significant.

“We no longer have to worry about contaminated water or illnesses. Our children are safer and our homes are cleaner,” Leisido said.

Seven villages, including Soito were declared open defecation free in a ceremony held in August attended by Roba Wario - county Wash coordinator, director promotive and preventive health Hassan Halakhe and subcounty public health officer Redento Dabelen.

Hokile Boku said the project is significant in promotion of sanitation and hygiene. “This is a resounding success that showcases the transformative impact of the CLTS in the intervention areas,” he said.

Korr/Ngurunit ward chief Charles Leparasanti was awarded a certificate in recognition of his efforts to ensure the area achieved an open defecation free status.

He advised the communities to set up latrines every time they migrate to avoid backsliding.

MCA Daud Arkhole said since the inception of CLTS, there has been a reduction of sanitation-related diseases.

“I recommend consistent follow-up of migrating villages in order to enhance proper use of latrines,” he said.

From bushes to cemented pit latrines, Soito’s journey reflects the power of local action, education and dignity.

In a place once defined by open fields, the community now stands united by something far more powerful, ownership of their health and future.

For lasting impact, there is a need for greater government involvement in ending open defecation by prioritising sanitation in national and county policies.