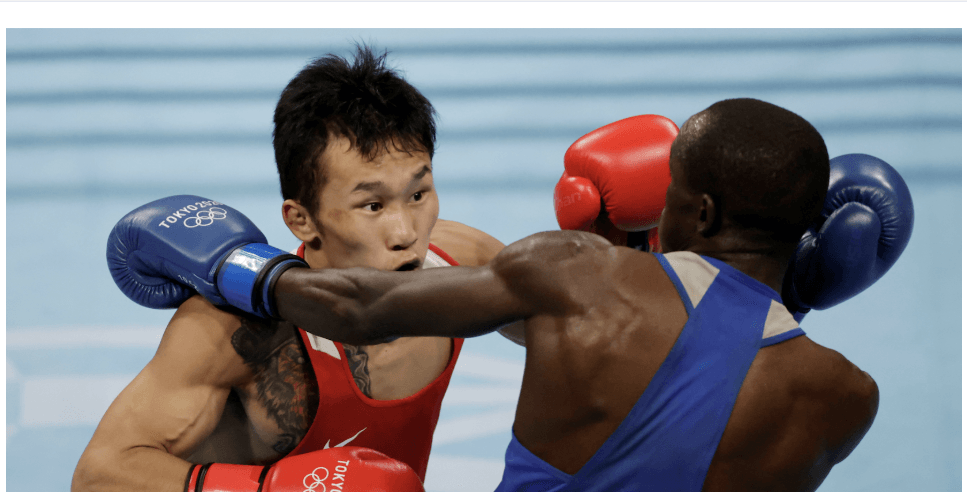

Hit Squad's Robert Okaka in action against Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat/HANDOUT

Hit Squad's Robert Okaka in action against Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat/HANDOUT Kenya’s last flame at the IBA Men’s World Championship dimmed on Thursday night when Robert Okaka fell in a bruising quarterfinal against Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat, ending the Hit Squad’s gritty pursuit of a long-awaited world medal.

Fondly known as “One Man Ngori”, Okaka stepped into the quarterfinals carrying the weight of a nation’s hopes, but Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat closed the door on Kenya’s last surviving medal chance in Dubai.

By the final bell, the Hit Squad’s run—gritty, emotional, imperfect—had officially reached its limit.

Okaka had punched his way into the conversation after an emphatic Round of 16 stoppage over Tunisia’s Rafrafi Youssef, a performance that blended ferocity with calm precision. For a moment, Kenya dared to believe.

But Dzhambulat was different. Measured. Efficient. Relentless in the quiet moments. By the third round, the Russian’s tactical discipline had smothered Okaka’s rhythm and muted the explosiveness that had carried him through earlier rounds.

Still, making the quarterfinal in a field this deep was no fluke. It was Kenya's strongest run in more than 40 years—a reminder that potential remains alive, even when the scoreboard reads otherwise.

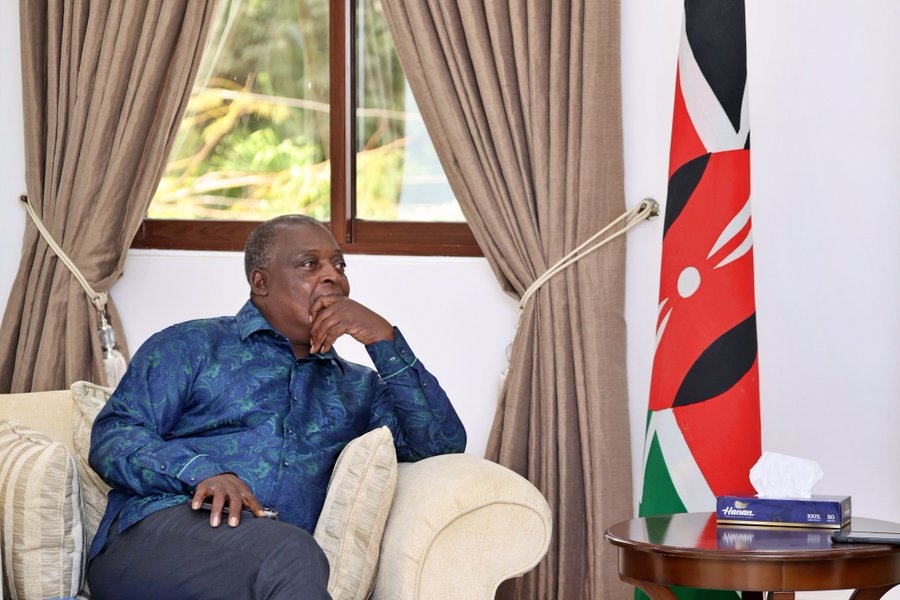

At ringside, Hit Squad head coach Benjamin Musa wasn’t dwelling on the defeat. His focus was wider, bigger. On the team. On the journey.

“We came to Tashkent with a young team, and they fought with everything they had,” Musa said. “The level here is unforgiving, but the boys never stopped believing.”

He talked less about outcomes, more about evolution.

“This championship exposed the areas we must tighten,” Musa said. “Punch volume, tactical maturity, and endurance—these are the things that separate you at the world level.”

Even as he dissected the campaign’s shortcomings, Musa’s optimism remained intact.

“We’re leaving with lessons that will carry us forward,” he said. “No fight here is wasted. Every bout matures a boxer.”

And on the team’s collective resolve?

“What I’m proudest of,” Musa added, “is how they responded to pressure. No one hid. No one backed off. That’s a foundation we can build on.”

Musa also acknowledged the energy from home.

“We felt the support from Kenyans everywhere,” he said. “It kept the boys motivated, even on tough days.”

Featherweight prospect Paul Omondi, just 21, stepped into a Round of 16 bout against Mozambican veteran Sigauque Armando Rugoberto—and took a 0:5 loss.

“Facing a seasoned boxer at that age is a tough ask,” Musa said. “But Omondi held his composure. That’s growth.”

Hit Squad's Robert Okaka in action against Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat/HANDOUT

Hit Squad's Robert Okaka in action against Russia’s Bizhamov Dzhambulat/HANDOUT Light Welterweight boxer Caleb Wandera delivered one of the Kenyan team’s most polished performances, but still dropped a 2:5 split to Argentina’s Villaba Lucas.

“A close fight is sometimes the best teacher,” Musa said. “Caleb showed ring IQ and discipline.”

For debutant Kelvin Miana, Kazakhstan’s Sabit Daniyal proved too sharp, too experienced. Miana lost 0:5, but the score didn’t capture his grit.

“Miana came out swinging—he didn’t fear the moment,” Musa said. “That’s what you want in a young boxer.”

Against Uganda’s Mulindwa Fahad, Washington Wandera produced a masterclass in poise and precision—clean jabs, measured footwork, smart combinations.

His commanding 5–0 win jumped him into the Round of 16 and gave Kenya its most dominant victory of the tournament.

“That fight showed what we can do when everything comes together,” Musa said. “Discipline, execution, composure—Wandera had all of it.”

Bantamweight boxer Shaffi Bakari showed grit but couldn’t turn the tide against Spain’s Lozano Serrano in the Round of 32.

Edwin Okongo, meanwhile, dropped a razor-thin split-decision bout to Israel’s Kapuler Ishchenko—a fight that felt balanced on a knife-edge.

“No result is a waste if the boxer grows from it,” Musa said. “Both boys fought with conviction.”

As the tournament wound down, Hit Squad captain Boniface Mugunde spoke with the poise of a leader who sees a bigger picture taking shape.

“This championship showed us exactly where we stand,” Mugunde said. “We’re not where we want to be yet—but we’re coming.”

He praised the team’s composure against world-class opponents.

“The boys stepped into tough fights and held their nerve,” he said. “We kept the Kenyan fighting spirit alive every night.”

For Mugunde, the lessons extend far beyond technique.

“Our unity grew here,” he said. “We pushed each other. We stayed connected. That matters on a stage like this.”

And to the fans?

“Kenyans believed in us,” Mugunde said. “That support carried us through the toughest moments.”

The coaching staff leaves Tashkent with a sharper sense of what must improve. Conditioning. Tactical patience. Volume punching. Footwork efficiency.

Coach Musa summed it up succinctly:

“We didn’t get medals, but we did get clarity,” he said. “That clarity becomes the blueprint.”