Coach Jepchumba Bundotich on her graduation at the House of Coaches in Iten/ CHARLENE MALWA

Coach Jepchumba Bundotich on her graduation at the House of Coaches in Iten/ CHARLENE MALWA When teacher and coach Jepchumba Bundotich was shortlisted for the Kenya–France Sports Development Course in 2023, she simply expected to sharpen her athletics coaching skills.

Two years later, she has become a model of what structured, science-based and inclusive sports education can achieve — blending classroom teaching, community training and international best practice to nurture the next generation of athletes in Elgeyo Marakwet County.

The course, implemented through a partnership between the French Embassy in Kenya, the Ministry of Sports and the University of Nairobi’s Sports Science Department, has trained over 200 local coaches since 2022.

It focuses on strength and conditioning, youth development and safe sport practices.

According to the Ministry of Sports’ 2024 Annual Report, the initiative has increased the number of certified coaches by 37 per cent nationwide, addressing one of the key gaps in Kenya’s long-term athletic success.

“This programme was wonderful,” Jepchumba said. “We were trained in athletics, basketball, handball and strength and conditioning for six weeks. It helped us understand the science behind sport — why we train specific muscles, how to individualise programmes and the stages of talent development from age six to 23 and beyond.”

Building champions from the ground up

Jepchumba, who teaches at Kamosor Secondary School, has transformed her family’s land into Kamosor Camp, where she trains junior athletes alongside her husband, Stephen Ruto.

The camp nurtures boys and girls as young as 11, combining physical training with life skills and spiritual mentorship.

Among her standout athletes is Agnes Ng’etich, whom she began coaching in her early teens. Under Jepchumba’s guidance, Ng’etich rose from the junior ranks to global stardom, shattering the women’s 10 km world record in January 2024 with a time of 28:46, becoming the first woman to break the 29-minute barrier.

Earlier, she had clocked 29:24 in a women-only 10 km race in Romania.

Ng’etich’s rise — from a rural training camp to global acclaim — exemplifies the impact of structured grassroots coaching. “In Kenya, we often identify talent but fail to nurture it progressively,” Jepchumba explained.

“This course helped me understand that development has stages — from discovery to nurturing and eventually professional competition. I can now identify and support young athletes without pressure, even within schools.”

Coaching as education

The Kenya–France programme aligns with Kenya’s Competency-Based Curriculum (CBC), which integrates physical education and talent development into academic learning.

Jepchumba, who teaches English, Sports, Arts and Religion, says this new approach has made her school a hub for holistic education.

“CBC allows learners to express their talents early,” she said. “Now I can teach the physical aspects with confidence — understanding strength, endurance, recovery and even cross-training techniques like cycling or swimming.”

Her headteacher, Samuel Kimaiyo, describes her as “an all-round coach” whose influence has transformed the school’s sports performance.

“Under her guidance, Kimworo and Kamosor have consistently produced national and East African representatives,” he said. “Last year, three girls reached the national level and one qualified for East Africa. Her passion has inspired both students and fellow teachers.”

Rural roots, global standards

Kenya’s athletic heritage remains unparalleled, yet gaps in infrastructure and coaching persist.

According to World Athletics (2024), over 62 per cent of Kenya’s elite athletes hail from the Rift Valley, but only 18 per cent of rural schools have standard training facilities.

UNESCO’s 2023 Global Sports Education Report ranked Kenya’s sports infrastructure index at 0.41, below the African average of 0.53, citing inadequate equipment, fields and qualified trainers.

“Facilities are our biggest challenge,” Jepchumba admitted. “Many schools don’t have fields, pools or hurdles. We improvise — using wooden bars, sharing fields, even cycling on rough roads. But if we had proper facilities, the results would be very different.”

At Kamosor Camp, resourcefulness is a way of life. Training begins at 5 am, with school-going athletes joining before classes and older ones later in the morning. Elite athletes follow customised evening sessions.

The setup mirrors elite environments such as France’s Miramas High-Performance Centre, where Jepchumba trained during the exchange programme.

“In France, we saw structured daily routines — combining sport, nutrition, recovery and mental health,” she said. “That’s what we now apply here, within our means.”

Building local capacity

First piloted in 2021, the Kenya–France initiative aims to decentralise sports science knowledge by training teachers and coaches as community developers. The Elgeyo Marakwet cohort included 12 teachers who now serve as “trainers of trainers” across schools and community centres.

County statistics show that between 2022 and 2024, the number of active sports programmes in local schools rose by 42 per cent, while youth participation in athletics and ball games nearly doubled from 1,500 to 2,700 learners.

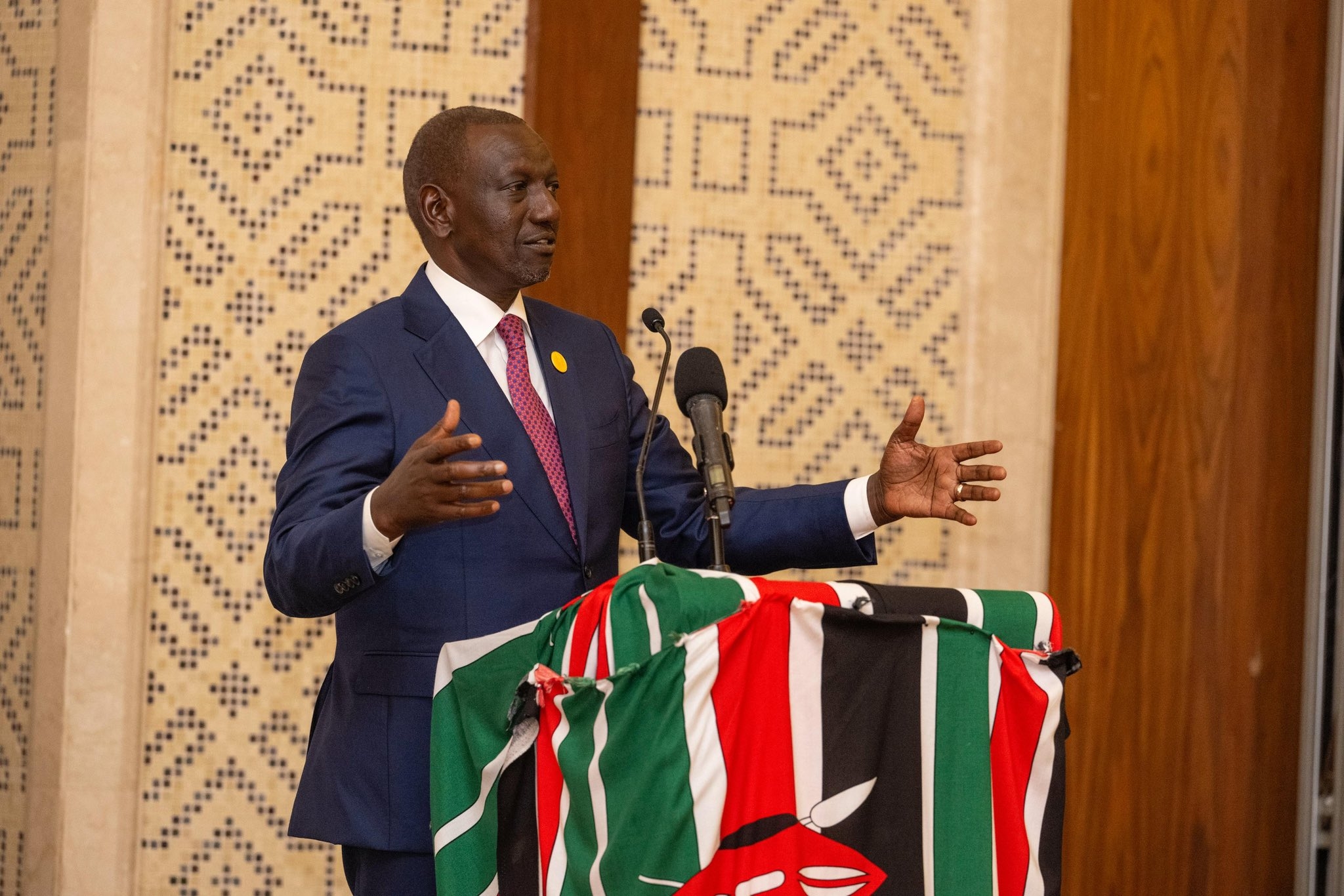

Governor Wisley Rotich, whose administration co-funded logistics, said the impact has been immediate.

“We now have a structured system where sports and education work together,” he noted. “Our goal is to have a qualified coach in every school to mentor and protect young athletes. The France–Kenya partnership has been key to building that foundation.”

The science behind the track

At the heart of Jepchumba’s work lies sports science — an area long neglected in Kenyan grassroots coaching.

A 2024 University of Nairobi Sports Science Department evaluation found that 68 per cent of teachers who underwent the bilateral training now integrate physiological and biomechanical principles in their sessions.

“We went into specifics like muscle function, injury prevention and recovery,” Jepchumba said. “We learned about specificity — you can’t give a sprinter a long-distance programme. Now we can design and justify every session.”

Her focus on individualisation and specificity has boosted her athletes’ performance and reduced injuries. The programme’s practical focus, combining classroom theory with hands-on training at the Kenya School of Sports and Miramas Centre, proved transformative.

“We were paid for our studies at the University of Nairobi,” she added. “We’re set to graduate in December after two semesters in sports science. It’s been life-changing.”

National gaps and the road to reform

Despite such gains, the coaching deficit remains significant. Athletics Kenya (2024) estimates the country has fewer than 1,200 certified coaches, far below the 5,000 needed nationwide.

The Sports Registrar’s Office reports that 40 per cent of grassroots coaches operate informally, with no accreditation or safety training — a gap the Kenya–France programme seeks to close.

The Ministry of Sports is developing a National Coaching Framework, expected in 2026, to standardise certification, ethics and athlete protection. It will align with the Safe Sport Policy, introduced after a series of gender-based violence cases in athletics.

“We even covered safe sport in our course,” Jepchumba noted. “It’s important for coaches to know their boundaries and protect athletes from abuse or exploitation. Discipline and respect are key.”

Her camp enforces a strict 21-rule code, balancing structure with mentorship.

“When results come out right, it’s fulfilling,” she said. “Some of our athletes have gone to the US on scholarships. That alone motivates me to keep going.”

Transforming young lives

Through Kamosor Camp and her school programmes, Jepchumba now trains nearly 40 athletes across different age groups — from CBC pupils aged 11–13 to teenagers competing at regional and national levels.

Her current squad includes Damaris Cherono, Brance Chebet and Mercy Chelimo, three promising Kimworo girls who reached the National Cross Country Championships this year, with one qualifying for the East Africa Games.

“They’re proof that early nurturing works,” she said. “If we start identifying and guiding talent from age nine or 10, we can build athletes who compete cleanly, safely and proudly for Kenya.”

A model for policy replication

Sports policy experts view the Elgeyo Marakwet experience as a model for replication nationwide.

A 2025 UNESCO Sports Policy Brief commended Kenya’s integration of school-based sports science and bilateral partnerships, noting that such approaches “create sustainable talent ecosystems by embedding sport within education systems.”

The Ministry of Education is now exploring similar collaborations for football, volleyball and handball, using athletics as a template.

French Ambassador Arnaud Suquet reaffirmed his country’s commitment to supporting the partnership, describing it as “a shared belief that sport is both an education and development tool.”

“This cooperation is not just about medals,” he said. “It’s about knowledge transfer, opportunity and empowerment — ensuring young athletes have the right support from school to elite level.”

Beyond the track

For Jepchumba, the journey is as personal as it is professional. Her days begin before sunrise, balancing classroom teaching, coaching and mentorship. But her vision goes beyond trophies.

“I’m always happy when I train people and they excel,” she said. “Athletics is my passion. What inspires me most is seeing them succeed — not just as athletes, but as disciplined, responsible people.”

Her philosophy mirrors the new direction Kenya’s sports sector seeks to institutionalise: structured, inclusive, science-driven and values-based coaching.