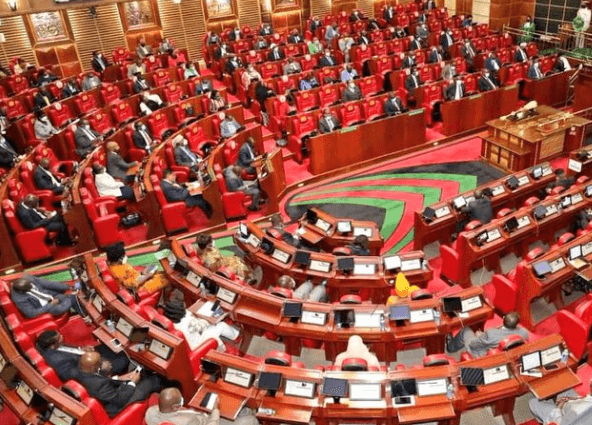

The parliamentary interviews of nominated Cabinet Secretaries have produced many comments – most, if not all, very critical. The MPs involved did not really know much.

They asked reasonable questions but had no follow-up. And they did not seem concerned about what most Kenyans are concerned about – issues of integrity particularly. And it was a disgrace that the house as a whole should overrule the recommendations of the committee on the Tourism nominee.

Many said it was a waste of time (and a lot of money involving many sitting allowances and a retreat to Mombasa to write the committee report). And it should be done away with, leaving the President’s choice untrammelled.

Many people have pointed out that this process can be traced back to the US Constitution and practice under which “the advise [US spelling of course] and consent of the Senate” to very many appointments is required. But it is not linked to the choice to adopt a US style system of government. This choice was made in the last few months of the constitution making process. The very first constitution draft, in 2002, said that a function of Parliament was “considering and confirming the President’s nomination of persons to serve in the Cabinet? (The reference to the President was an error – the PM would nominate and the President only formally appoint.)

The reason for this rule about National Assembly approval was because “The President shall not appoint …a Member of Parliament to the office of Minister”. So this was very different from a classic parliamentary system where Ministers must be members of Parliament who rose to prominence through their party and Parliament and would be well known to MPs. The reason for giving this role to Parliament was because they might not be familiar with the appointees, and those people were not democratically elected to anything. They were therefore to be at least approved by a democratically elected body.

The US model

When the “advise and consent of the Senate” rule was adopted in the US Constitution it was – according to Alexander Hamilton - to prevent abuses by the President, like nepotism, appointing one’s family members etc.

There were reason for giving this role to the Senate. One no doubt was because this was a body of people of greater maturity (a minimum of 35 years old). Also it was not a small body (that might be bribed or influenced) but was not a large body – Hamilton mentioned the possibility that the House of Representatives might grow to be 300-400 strong in the future (the same sort of size as our National Assembly now) – much too big he said. The House of Representatives, he said was also too fluctuating (having full elections every two years). The Senate was more stable as well as much smaller.

The model here

The job in our Constitution was given to the National Assembly. This is a large body (though a committee does the main work on this matter). And though it has a longer life than the US House, a big turnover does mean that many members come to this task with little experience. And they come to the task almost immediately after they take their seats, barely knowing their way around Parliament let alone understanding their role and that of CSs.

And, of course, one of the depressing aspects was the way in which, though a cross party committee unanimously rejected one nominee, the government MPs in the NA as a whole tamely went along with the President’s wishes.

In the US many people serve for years in Congress – including in the House. It is a valued career in itself. But here MPs still hope for some other favour from the president – either an actual appointment perhaps, or in some way being beneficiaries of presidential largesse. And they dismally fail to make their duty of oversight of government a reality. Hardly ever do they reject a nominee and when they do it is because of some perceived affront to them, the MPs, not because of any inability or other unsuitability to do the job.

And in many countries people are very dissatisfied with this sort of arrangement. A writer on Ghana observed instances of refusal to approve an appointment because of vindictive motives. Writers in the US sometimes complain of too many rejections by the Senate, though not usually of Cabinet Secretary positions.

Why ‘vetting’?

MPs tend to concentrate on whether the person has the qualifications for the job. The recent committee report on the CSs always speaks of the committee’s comments on the suitability of the candidates. This suitability itself might depend on various factors. One is a matter of formal qualifications and relevant experience. The second the apparent understanding of and attitude towards the particular role.

In order for the committee (and the MPs) to make useful judgments in these matters they must understand the nature of the role. I find the committee report – and Parliament’s own responses – weak on some of these issues. For example the conclusions about Mudavadi on suitability for Prime CS did not go into what the nature of that role is. It is mysterious. But without knowing what the office is supposed to do – and what the nominee believes it is supposed to do – how can a useful assessment be made of his suitability?

And when interviewing the prospective Attorney General, there was no effort to address the dual nature of that role. The AG is the government’s legal advisor, but also has a role under the Constitution to “promote, protect and uphold the rule of law and defend the public interest.” There is clearly potential for some conflict or tension between the government advisor and the rule of law upholder aspects of the job. But you would not think so from the committee’s report.

The committee did not want to approve the CS tourism nominee. The committee report does indicate that her responses to questions about policies she would adopt to enhance tourism seemed simplistic and elementary. The House as a whole, however, insisted that she was well qualified. But well qualified for what? She had a lot of experience running an NGO. But being CS does not involve running a Ministry. That is the job of the PS and his or her colleagues. The job of the CS is to develop policies. The public service carries out those policies.

Recent developments have blurred the distinctions between political appointments (especially CSs – we used to call them Ministers) and others. Even the phrase Cabinet Secretary (and do you know the difference between this and the Secretary to the Cabinet?).

Is the current system useless?

This current system, at least for CSs and PSs, is written into the Constitution, and is thus hard to change. Is it possible that it does serve some purpose?

Suppose we did not have it? We would then find that many of our Ministers were quite unknown to us. At least this public process reveals something about them.

Another aspect of the vetting is to check on how the actual appointment process operates. This fits with the idea that it is to prevent abuse of powers by the President. And if it did not exist, maybe there would be even greater use of this appointment power for dubious purposes, including nepotism, and political debt-paying. At least the President knows that his choices will be publicly scrutinised.

The vetting process could serve to remind appointees that they are accountable to Parliament. Oddly the Constitution says they are accountable to the President only. But in reality they are supposed to report to Parliament, and can be removed if Parliament decides to investigate their conduct, decides they are guilty of a breach of the constitution or of serious misconduct and says they should be removed. This is accountability. But Parliament’s superficial vetting process may undermine any sense of this accountability on the part of the CSs.

Will Parliament do a better job on the principal secretaries?