ART CHECK: Lesson from losing last molar tooth

Grandma used to tell me to ‘feast on your youth’

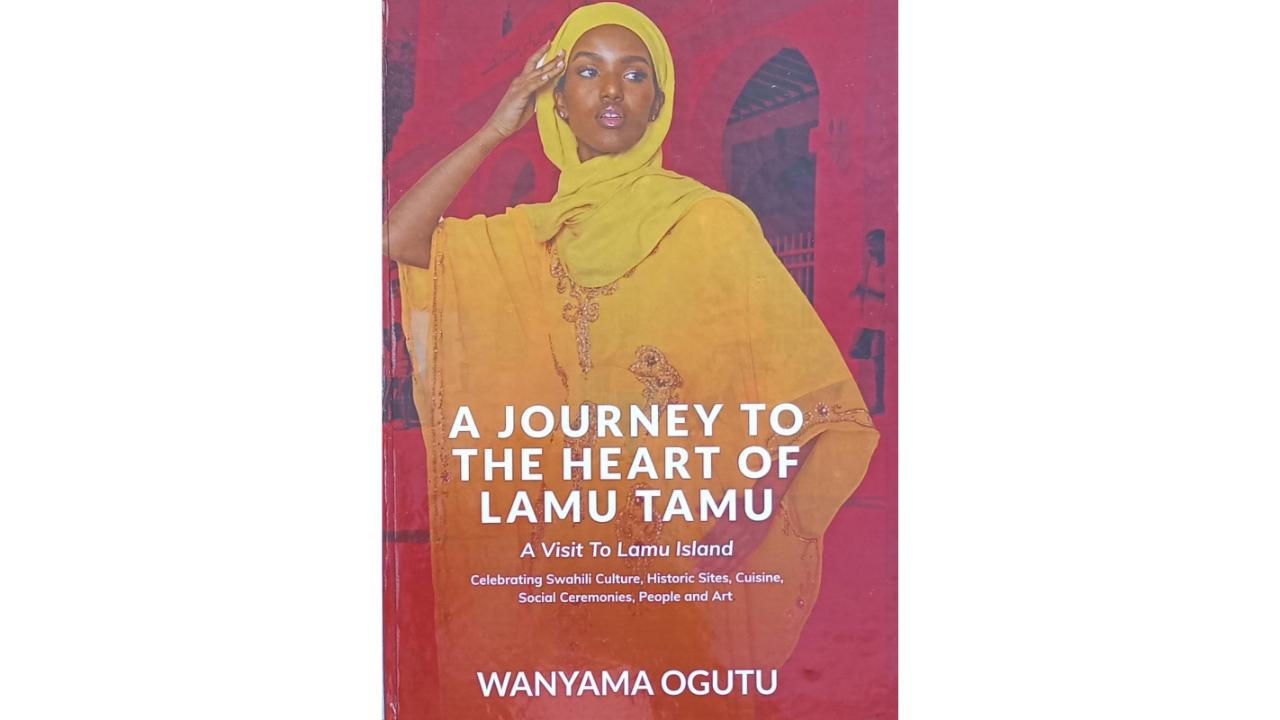

Wanyama Ogutu’s book marries history and art in scholarly way

In Summary

Audio By Vocalize

I went there to pay tribute to Mwana Kupona binti Msham, the earliest recorded Kenyan poetess, who’s Utendi wa Mwana Kupona still echoes across two centuries, placing her in silent dialogue with the likes of Goethe and Wordsworth.

Lamu’s sea breeze seemed to carry fragments of her verse, mingling with the call to prayer, the creak of ancient dhows and the whispers of coral-stone walls.

Years later, recently, when one of my former arts students, Wanyama Ogutu, retraced those same cobbled paths, his muses stirred with such force that they birthed A Journey to the Heart of Lamu Tamu (2025), his debut book, a work of art that marries prose and picture, scholarship and sensation, history and art.

Ogutu’s background bespeaks of the power of resilient introspection that defines artists from others in society. His formative years in Nairobi of the eighties, spent navigating the socio-economic complexities of Huruma and Mathare, and later, the coastal town of Mombasa, forged a character defined by keen observation.

While his parents, far from the world of artistic pursuits, may not have recognised his nascent creative inclinations, his early life was a crucible where his artistic instincts were honed. This early struggle to be “seen” by his family and the later validation he found in his high school art teacher underscores a recurring theme in his work: the search for belonging and the validation of one’s creative identity. His stammer, a barrier to verbal communication, ironically became a catalyst for his artistic and written expression, pushing him to find alternative languages to convey his inner world.]

His new book is a product of his Master of Fine Arts fieldwork, an academic pursuit that has become a deeply personal quest. The book recounts his field trip and immerses us in ethnographic study disguised as a narrative.

Ogutu’s decision to choose Lamu was deliberate. He saw it as a location with a living entity couched on unique historical and cultural identities.

The narrative arc, which begins with a serendipitous encounter in a Nairobi bus terminal and culminates in a profound interaction on the island, mirrors the gradual process of anthropological discovery.

The book’s structure allows the reader to experience Lamu as Ogutu did: slowly, intimately and with a growing sense of wonder. The narrative is richly layered with historical context, personal reflections and fictional elements, a deliberate choice that elevates it beyond a simple travelogue to a work of academic and artistic merit.

The most compelling aspect of Ogutu’s work is his seamless integration of two seemingly disparate disciplines: writing and fine art. He posits that both are merely different “languages” for the same form of storytelling. This perspective is evident on each single page. His prose is imbued with the vocabulary of an artist; he describes the “textures of the island scene” and the “intricate Swahili patterns” with the precision of a brushstroke.

This synesthetic approach allows him to capture both Lamu’s physical appearance and its very essence: its colours, its light and its mood. For Ogutu, his sketchbook and canvas are as essential to his narrative as his stylus, providing him with a medium to see the world “through the elements of line, colour and texture,” which he then translates into a literary form.

The book, divided into chapters of about 50 pages, offers a masterful synthesis of image and text. Each section feels like a carefully curated exhibition. A chapter on the island’s narrow, labyrinthine alleys, for instance, is punctuated by a full-page photograph that captures the scene in a wash of soft, fading light.

The image shows a single figure, their silhouette a dark contrast against the sun-bleached walls, a donkey laden with goods disappearing into the shadows. The air, thick with the scent of cloves and salt, seems to hum from the page. This visual commentary is followed by Ogutu’s poetic prose: “Here, the walls whisper secrets of centuries past, each crack a chronicle, each worn step a testament to the endless rhythm of life lived in the embrace of ancient stone.”

Another chapter, perhaps dedicated to the island’s bustling seafront, is accompanied by an image of a traditional dhow boat at sunset.

The sky is a canvas of fiery oranges, deep magentas and soft lilacs, the colours bleeding into the tranquil water. The sails, catching the last of the day’s golden light, appear to be woven from pure gold.

Ogutu’s words dance alongside this image: “The dhows are the island’s beating heart, their sails the wings of stories carried on the sea breeze, their wooden hulls groaning with the weight of both today’s catch and a thousand years of history.”

This deliberate pairing of text and image creates a sensory and emotional experience that is both intellectually stimulating and deeply moving. His academic journey at Kenyatta University, where his ongoing research focuses on using natural plant resources for art to preserve Swahili culture, provides the intellectual scaffolding for this book.

This new book is, therefore, an entertainment piece and more. It is a scholarly contribution that demonstrates how creative expression can be a legitimate form of knowledge production.

In my opinion, it challenges the conventional divide between personal creative practice and academic research, arguing that both can co-exist to produce a richer, more holistic understanding of a subject. Ogutu’s work invites the reader to reconsider the value of indigenous knowledge and cultural preservation in an increasingly globalised world.

The core message of the book, that belonging is found where one feels “seen and inspired productive”, is a powerful statement on identity and community in our modern African context. His approach bridges the gap between scientific inquiry (the process of colour extraction) and artistic expression, giving him a niche as new, truly innovative figure in both Kenyan literature and fine art.

One can buy a copy of the book directly from the artist at:

[email protected]

Grandma used to tell me to ‘feast on your youth’