African countries strive to secure digital and technological sovereignty because it is the only path to independence, true equality, and control over their resources and infrastructure in the modern world.

However, the active participation of foreign tech companies in building Africa’s digital infrastructure could entrench the continent’s dependence on external platforms, lead to data leaks, and limit opportunities for local innovation, writes Marina Krynzhina, Associate Professor at the Department of International Journalism at MGIMO.

Science and technology are the main drivers of development on the African continent. Ensuring digital sovereignty without significant investment in scientific and technological development is impossible.

Nevertheless, the systematic and collective efforts of African countries to develop science and technology on the continent are undeniable.

This is confirmed, among other things, by the public promise of South African President Cyril Ramaphosa to use his country’s G20 presidency in 2025 “to place the needs of Africa and the rest of the Global South more firmly on the international development agenda.” The results of South Africa’s efforts in this respect will be summarised at the Johannesburg summit at the end of the year.

Another significant event was the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, held from June 30 to July 3, 2025, in Seville, Spain under the auspices of the UN, where African leaders pinned high hopes on attracting investment in science and technology development.

The Seville Agreement, adopted by consensus, includes a set of commitments to reform sovereign debt. If the provisions outlined in the document are actually implemented, it will be a major victory for the continent, as the debt obligations of a significant number of African countries prevent them from reallocating budgets in favour of science and technology development.

However, lack of investment is not the only obstacle to achieving coveted technological sovereignty. To achieve digital independence, Africa still faces a tangled web of challenges: weak infrastructure, a lack of indigenous technology and dependence on foreign actors, labour shortages, limited access to electricity, a gender gap in technology use, regulatory and legal barriers, and political instability. These are just a few of the discouraging figures.

Africa still accounts for less than 1% of global data centre capacity, despite mobile traffic growing on the continent at an annual rate of approximately 40%, which is almost twice the global average. Furthermore, Africa lacks its own interconnectivity system, without which it cannot become an equal participant in global communications. The undersea cables that reach the continent and provide internet access to Europe and America are entirely controlled by Western European countries.

Electricity supplies are limited: only 43% of the population has reliable access to electricity. More than 409 million Africans live within 10 kilometres of land-based fibre-optic networks. However, broadband adoption remains low due to affordability, quality gaps, and limited last-mile coverage in rural areas.

Despite the existence of data protection laws in 36 African countries and attempts to ratify the 2014 Malabo Convention, only 16 countries have acceded to it, and most countries have weak regulatory frameworks and fragmented cybersecurity policies. As Western companies actively expand into the construction and maintenance of data centres in Africa, the shortage of locally qualified cloud technology and cybersecurity specialists is becoming increasingly acute.

In an effort to overcome these challenges, the African countries are acting as a united front. Domestic initiatives within African countries are aimed at achieving political agency and developing a sovereign African science sector. Thus, the updated Science, Technology, and Innovation Strategy for Africa (STISA-2034), adopted by the African Union, focuses on the creation of local data centres, the development of a continental digital infrastructure, and strengthening sovereignty in data management.

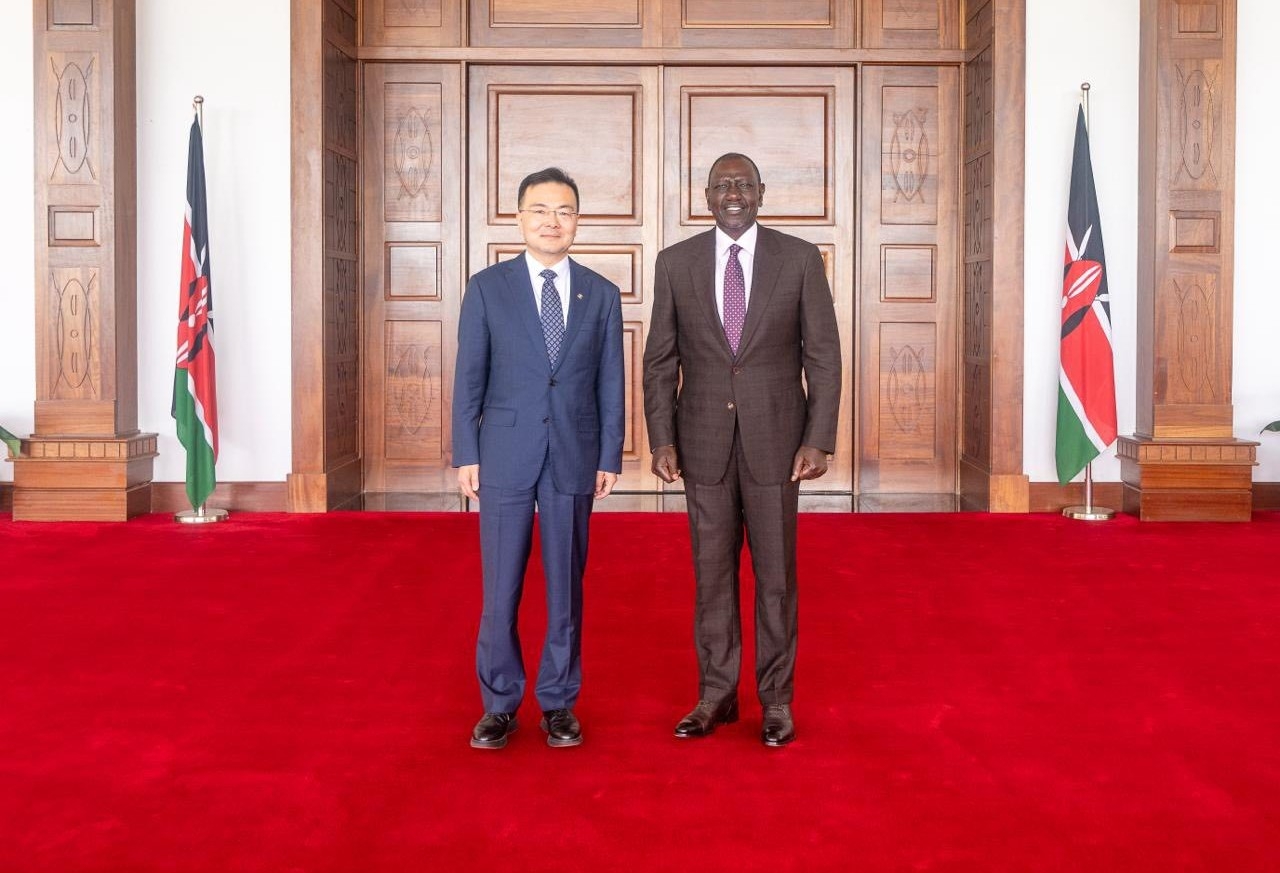

The African Union and national governments aim to overcome dependence on foreign platforms and Big Tech corporations by supporting open access to scientific knowledge (for example, AfricArXiv) and local citizen science initiatives (Pan-African Citizen Science e-Lab). African countries also recognize the strategic role of AI in achieving the continent’s technological sovereignty. For example, Kenya approved the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2025-2030, thus becoming the first country in East Africa to develop a regulatory and structural approach to AI development.

Information telecommunications technologies (IT) have emerged as an everyday human tool in the modern world. They are also an important means to develop the state and society. In other words, whoever has a grip on advanced IT has a grip on the world.

There is no

doubt that the advancement of IT is accompanied with a fast growth of

artificial intelligence (AI), which has also become part of our everyday life.

The African countries are not staying on the sidelines in this regard and are

rapidly adapting their economies to new realities, including IT and AI.

At the same time, practical steps being taken to achieve digital independence are focused on attracting external investment and therefore fundamentally contradict the declared desire for sovereignty.

For example, Zimbabwean billionaire Strive Mosiywa, who owns Cassava Technologies, announced that he is building Africa’s first AI factory in partnership with Nvidia, and the project is already well underway. During the World Summit on Artificial Intelligence in Africa, the government of Rwanda, represented by the Ministry of ICT and the Gates Foundation, signed a memorandum of understanding, which provides for the creation of an Artificial Intelligence Scaling Centre in Rwanda. Another “achievement” for the entire continent, according to the African media, is the decision by the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, to allocate $100 million to the regional data centre developer and operator Raxio Group for the construction of data centres from Ethiopia to Mozambique.

The main, publicly stated goal of all these initiatives is to reduce dependence on foreign technologies, accelerate digital transformation, and ensure Africa’s cherished digital independence. However, the implementation of each of these projects will only strengthen this dependence.

It is reasonable to say that sustainable development in the region is impossible without external investment and the transfer of advanced foreign technologies. Empirical studies of the impact of AI technologies on sectors such as agriculture and energy have shown that the implementation of AI can solve many infrastructure problems.

Even small improvements, such as precise sowing time and optimised irrigation and fertiliser application, can reduce costs and double crop yields.

However, the active participation of Western companies in the development of digital infrastructure in Africa should arouse, if not suspicion, then at least a certain scepticism. China, the EU, the US, and India are actively competing for influence in Africa in the scientific and technological fields, each offering its own model of cooperation.

While in theory Africa is increasingly setting its own agenda, transforming itself from an object to a subject of science policy, in practice, African countries are effectively ceding the reins of power in this area.

Africa is capable of developing a model of scientific and technological sovereignty and communications that could be of interest to other regions of the Global South. In Asia and Latin America, technological models are more often built on the adoption of existing solutions and the localisation of international corporations (for example, electronics production in Mexico or Vietnam). In Africa, innovation often emerges from extreme resource scarcity.

The M-PESA mobile payment system in Kenya took off in response to the lack of a developed banking infrastructure. There are no analogues in terms of scale and social reach in either India or Brazil. Irembo’s digital services in Rwanda were created not to simplify existing services, but to compensate for their absence. These examples could serve as the foundation of a unique model for scientific and technological development across Africa – digitalisation that replaces, rather than simply tries to catch up.

Multilingual scientific platforms targeting local audiences and the continent’s cultural and linguistic diversity are also developing in Africa. The emergence of educational networks such as PACS e-Lab has engaged hundreds of citizens from more than 40 countries in research in astronomy and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education.

The role of non-state actors in scientific development on the continent is growing: non-profit organisations such as AfLIA and ACTS, which focus on integrating science and society, are increasing scientific literacy and information accessibility.

Africa needs to secure digital and technological sovereignty – this is the only path to independence, true equality, and control over its resources and infrastructure. Without digital sovereignty, African states risk remaining mere consumers of foreign technologies, deprived of access to source code, standards, and strategic management.

The active participation of Western companies in building digital infrastructure could entrench dependence on external platforms, lead to data leaks, and limit opportunities for local innovation.

A sovereign path necessitates not only foreign investment and equal access to technology, but also investment in domestic scientific research, local talent, technology, and a regulatory framework grounded in African interests and values.

This will determine whether

Africa will become a new “digital colony” or maintain its independence.