When Dr Ouma Oluga first appeared on the national stage nearly a decade ago, he was not the polished, consequential bureaucrat seated behind a mahogany desk at Afya House.

He was a defiant young doctor in a white coat — leading street marches, facing riot police and demanding better pay and working conditions for Kenya’s medics.

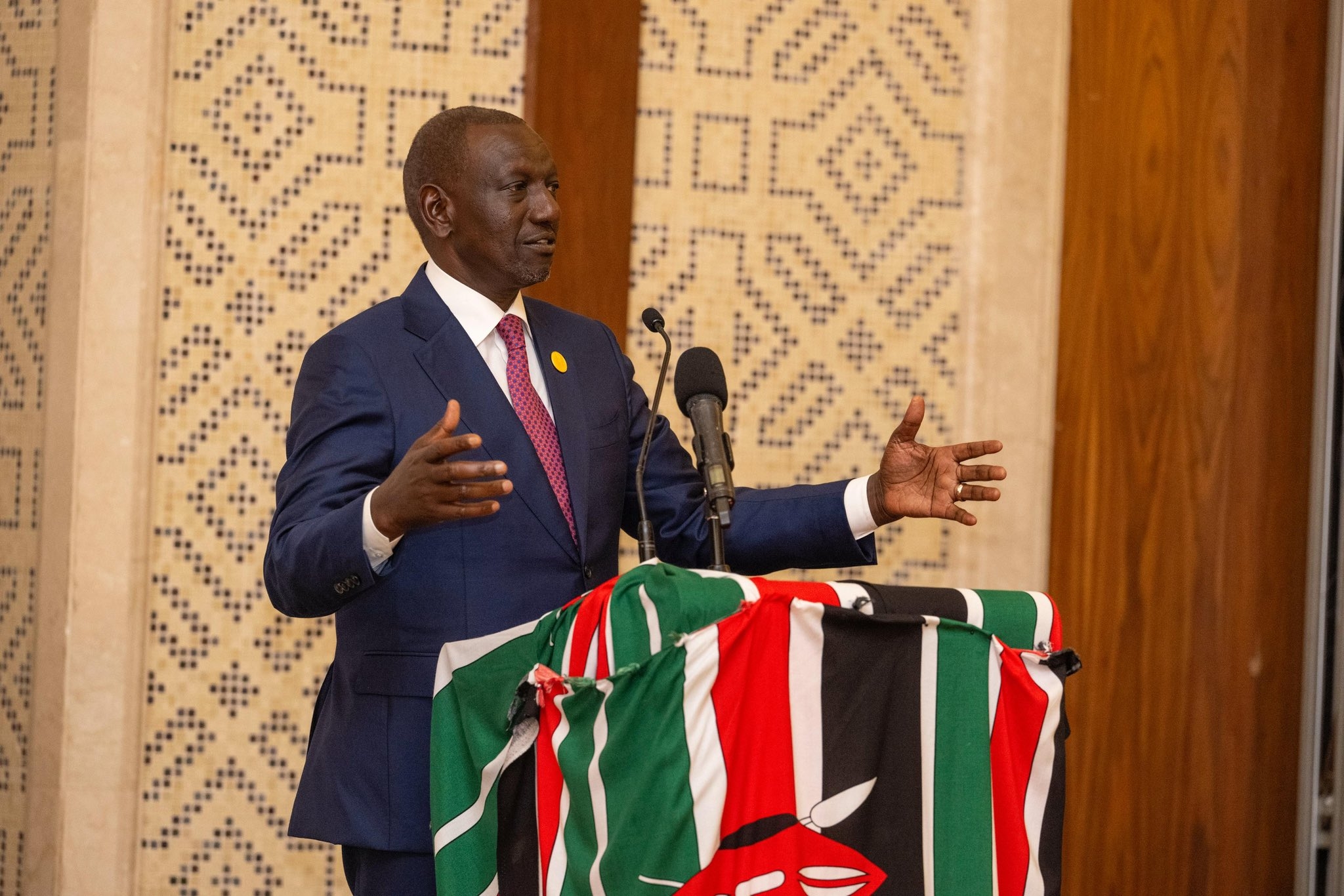

Today, that same man sits at the heart of government as the Principal Secretary for Medical Services — one of President William Ruto’s most visible technocrats driving the administration’s universal health coverage agenda.

His transformation from fiery union leader to top state official has drawn admiration and curiosity in equal measure. It not only speaks to the changing relationship between activism and governance in Kenya, but also to Oluga’s growing influence on the national stage.

A graduate of Moi University and the University of Nairobi, Oluga rose to prominence in 2015 when he was elected secretary-general of the Kenya Medical Practitioners, Pharmacists and Dentists Union.

It was a turbulent period in the health sector — doctors were striking, hospitals were understaffed and counties were struggling under devolution.

Young, articulate and unafraid, he quickly became the face of a restless medical workforce demanding dignity and fairness. His speeches combined professional idealism with sharp political critique. During the 2016–17 doctors’ strike, he endured arrests and vilification but held firm, ultimately securing improved pay and working conditions.

Among his major victories was calling on both national and county governments to clear millions of shillings in salary arrears owed to doctors since 2017.

For years, medics had complained of delayed pay following devolution’s payroll disruptions. This year, many finally smiled to the bank after payments running into hundreds of millions were processed — a milestone that restored confidence within the medical fraternity.

Yet, even in his activist days, Oluga’s rhetoric went beyond paychecks. He consistently framed doctors’ demands as part of a broader call for systemic reform — governance, accountability and the need for a functional, equitable health system. That reformist streak would later define his technocratic career.

When he resigned from KMPDU in 2020 to join the Nairobi Metropolitan Services as chief officer for health, many were stunned.

How could the fiery activist work within the same system he had long condemned? But those close to him say the move was strategic — a chance to test reform from within.

At NMS, Oluga was thrust into a bold experiment: building health facilities in informal settlements, recruiting medical staff and restoring trust in a devolved health system.

In less than two years, he helped make operational several hospitals across Nairobi’s slums, bringing primary healthcare closer to the people.

Colleagues described him as results-oriented — known to visit construction sites and clinics unannounced. The NMS experience became his proving ground for national service.

That opportunity came in April this year, when President Ruto appointed him PS for Medical Services in a reshuffle aimed at strengthening service delivery.

His appointment symbolised more than bureaucratic change — it was a political statement that the administration wanted “doers, not just loyalists,” in key positions.

Political analyst Alexander Nyamboga describes Oluga as “a consequential figure nationally and within the Luo nation.”

“Oluga’s rise has been meteoric,” the analyst says. “President

Ruto’s trust in him following the Cabinet reconstitution after the Gen Z-led

protests speaks volumes about his competence. He is also among the few Luo

professionals who earned Raila Odinga’s confidence.”

Indeed, insiders say Oluga was among professionals Raila recommended for PS appointments following his handshake with Ruto.

Health reform is a pillar of Ruto’s Bottom-Up Economic Transformation Agenda. Central to it is the rollout of the Social Health Authority and the Taifa Care programme — a replacement of the old NHIF model with a more inclusive insurance system.

As PS, Oluga’s task is to translate this ambitious policy into tangible results: financing hospitals, securing medicine supply chains and digitalising health records. He has promised to “shift focus from bricks to medicines” — a subtle rebuke of past regimes that prioritised buildings over essentials like drugs and staff welfare.

“Kenyans don’t need new hospitals without medicine,” he recently remarked. “They need functioning facilities with drugs, equipment, and motivated workers.”

Oluga’s union background has proven invaluable. Within the ministry, he commands rare respect from doctors, nurses and county executives — a bridge between government and the professionals implementing its agenda.

His influence was evident when, after Raila’s passing in India, the Odinga family included him among key figures that accompanied the former Prime Minister’s body back to Kenya. Insiders say Oluga played a pivotal role in convincing the state to posthumously honour Raila with the country’s highest civilian award — the Chief of the Order of the Golden Heart (First Class).

Although he insists he is “a public servant, not a politician,” Oluga’s ascent is undeniably political — positioning him for a potential future role in both Luo and national leadership.

In a government under constant pressure to deliver amid economic strain, President Ruto’s elevation of a former union leader with reformist credentials was both strategic and symbolic — co-opting a potential critic while reinforcing the image of a reform-driven administration.

Analysts see in Oluga the archetype of a new-generation technocrat: a professional who can design policy while carrying the moral weight of activism. His presence lends credibility to the administration’s promise that UHC is not just a slogan but a serious reform agenda.

“Oluga’s appointment neutralised a potential source of resistance,” governance scholar Robert Ongaro of Kenya Methodist University says. “Instead of fighting unions, the government brought one of their brightest to the table.”

Still, the honeymoon may be short. The Ministry of Health remains one of Kenya’s toughest bureaucracies — marred by alleged cartels and intergovernmental friction. Reforming it will demand both technical acumen and political courage, qualities Oluga is said to possess in rare measure.

Beyond bureaucracy, his journey mirrors Kenya’s evolving political landscape — the integration of professional activism into governance. His story illustrates how the state can absorb critics and turn them into agents of change. Yet it also raises enduring questions: does joining the system blunt one’s reformist edge? Can an insider truly challenge the structures that sustain the status quo?

For now, he stands as one of the most intriguing figures in President Ruto’s administration — a symbol of continuity between activism and policy, and proof that Kenya’s public service is gradually opening its doors to younger, reform-minded professionals.

The unionist-turned-technocrat may well define not just the future of Kenya’s health sector — but also the next chapter of its political evolution.