In the heart of East Africa, Kenya stands as a tapestry of diverse ethnic threads, yet one narrative has been systematically overshadowed: the profound Maasai imprint on the nation's identity.

From the snow-capped peaks of Mt Kenya to the fertile hills of Western Kenya, Maasai heritage echoes through place names, clans and even colonial treaties that robbed them of ancestral lands.

As we reflect on this, it's time to confront an uncomfortable truth—Kenya is, in many ways, Maasai country, and acknowledging this could heal colonial wounds and foster true national unity.

Consider Mt Kenya's majestic peaks: Batian, Nelion and Point Lenana. These are not arbitrary labels but tributes to Maasai laibons—Mbatian, his brother Nelieng and son Lenana—named by British explorer Halford Mackinder in 1899.

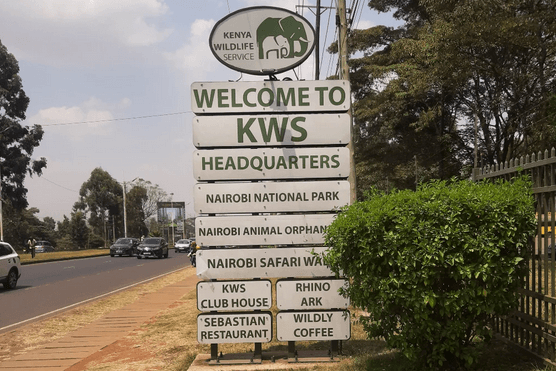

This mountain, sacred to the Kikuyu as Kirinyaga, bears Maasai names because their pastoral dominion once stretched from the Rift Valley and beyond, influencing geography and culture. Places like Nairobi (Enkare Nyrobi, meaning "cool waters"), Naivasha (Enaiposha, "heaving waters") and Laikipia, once a seat of Maasai spiritual leaders, testify to this legacy. Yet, history books often marginalise it, portraying Maasai as mere nomads rather than architects of Kenya's landscape.

This erasure intensifies in Western Kenya, where cultural mingling reveals a vibrant, underappreciated fusion. In Malava, Kakamega county, a melting pot of Luhya, Luo, Kalenjin and Maasai influences thrives. Clans like Abakhabi, linked to Iloikop Maasai, or Kwavi, Abashimuli and Bamwende have integrated into Luhya society, their members now speaking local dialects but carrying Maasai bloodlines.

Shared names, like Kaikai, Soita and Sambu, whisper of ancient interactions, perhaps from Nabongo Netia's 19th-century alliances with Maasai warriors against Luo threats. Even the late Mzee ole Kisero, a patriarch in Kaliwa and reportedly the last Maasai speaker in South Teso, underscores pockets of linguistic survival amid assimilation.

Oral histories further illuminate Maasai-Kikuyu ties, suggesting assimilation into Kikuyu communities after livestock diseases such as rinderpest decimated Maasai populations in the late 19th century. This could explain population disparities: Kikuyu comprise about 17-20 per cent (around 8-11 million) of Kenya's estimated 58 million people, while Maasai are roughly 2.5 per cent (about 1.4 million).

Names like Nyokabi—meaning "daughter of Ukabi" (Maasai lineage)—and cultural parallels, such as beaded bangles, necklaces and enlarged earlobes, bear testament to this blending. These exchanges, born from raids, alliances and the Anglo-Maasai treaty displacements, enriched Kikuyu society while diminishing Maasai numbers.

Tellingly, Kwavi is a name also found among the Kalenjin (Kipkwobek), Taita and Chagga (Akobi).

This intermingling extends to the Wanga Kingdom, centred in Mumias, also known as ancient Lureko, blending factual history with interpretive flair by tracing origins to Buganda princes.

Legends tell of Wanga, a descendant of Buganda royalty by lineage, specifically a son of King Mwanga of Buganda, who went into hiding in Tiriki land and from there he sneaked to the Imanga kingdom where he masqueraded as a servant.

Mwima, the Imanga kingdom ruler, later learnt of Wanga's royal bracelet and quickly gave him part of his kingdom to rule. Years later, his progeny, Nabongo Mumia, was invited to King Edward VII's 1902 coronation but declined on the counsel of his Arab trader advisors, fearing a coup from a wing of the royal family.

The Wanga kingdom's claimed expanse to Naivasha or Jinja may be exaggerated, but it highlights fluid pre-colonial boundaries, where Maasai mercenaries bolstered Wanga defences.

Colonialism's shadow looms largest here. The Anglo-Maasai Treaties of 1904 and 1911, signed under duress by Lenana, stripped the Maasai of fertile lands such as Laikipia for European settlers. Promised reserves "as long as the Maasai race shall exist" were revoked, displacing communities and severing kinships.

This was cultural genocide, fragmenting pastoral lifeways and fostering inter-ethnic distrust. Today, Maasai face tourism exploitation and land disputes, while their contributions—like naming conventions influencing Kikuyu, Kalenjin and Luhya—are dismissed as folklore.

Why does this matter in 2025? Kenya's post-Independence narrative has favoured dominant groups, perpetuating divides. It has been suggested that scholars like Prof Gideon Were, who chronicled Luhya history, omitted these Maasai-Luhya ties, leaving gaps that fuel misconceptions.

In an era of devolution and cultural revival, we must demand restitution: Return alienated lands, integrate Maasai history into curricula, and celebrate fusions like Malava's ethnic mosaic.

Opinionatedly, ignoring Maasai roots isn't just historical oversight—it is a betrayal of Kenya's multiethnic composition. By reclaiming this heritage, we honour warriors who shaped our borders and laibons whose names crown our mountains.

Social consciousness theorist, corporate trainer and speaker, agronomist consultant for golf courses and sportsfields, and author of 'The Gigantomachy of Samaismela' and 'The Trouble with Kenya: McKenzian Blueprint'