When the Kaira Looro Architecture Competition released its 2025 results earlier this month, a subtle but powerful concept stood out: Little Orbit, a minimalist yet emotionally rich kindergarten design set in Southern Senegal.

It earned a Special Mention, a rare nod from a jury composed of some of the world’s most revered architects, including David Adjaye, Kengo Kuma, Benedetta Tagliabue and Francis Kéré.

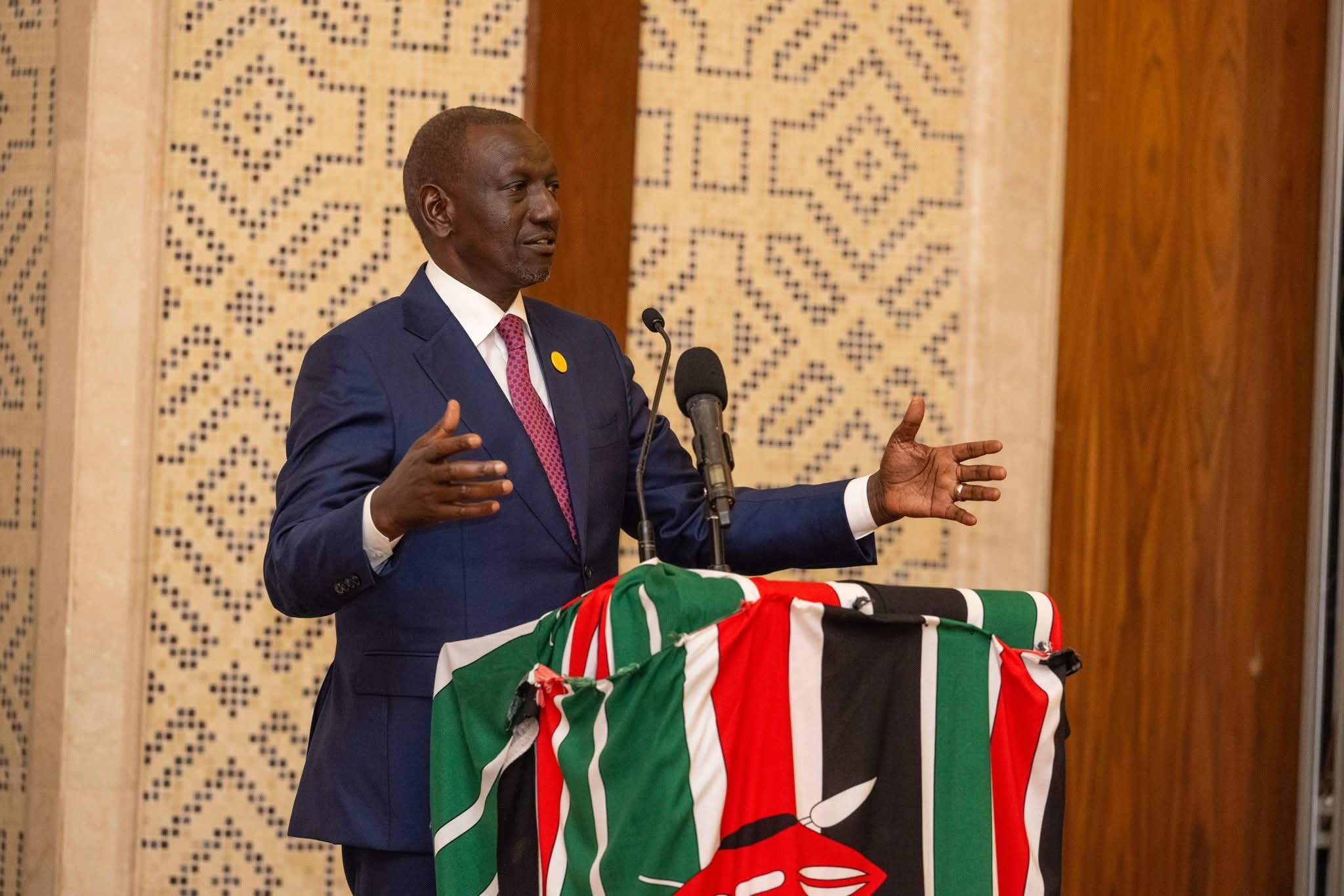

At the heart of this recognition is Addy Madoya, a co-designer of the award-winning project and a founding member of LondonConsult, a Nairobi-based architecture collective.

Alongside teammates Emmanuel Okello, Robert Omondi, David Koimburi and Daniel Omulo, Madoya is part of a new generation of African architects blending humanitarian sensitivity with bold, future-facing design language.

Madoya says their proposal deliberately rejects architectural clichés often imposed on childhood spaces. The sculptural, modern structure treats its young users with the dignity typically reserved for museums or temples.

That the project was recognised in a global competition dedicated to advancing humanitarian architecture is telling. It marks a broader shift in African design narratives, where local knowledge, material honesty and emotional architecture converge.

In this conversation, Addy Madoya reflects on Little Orbit, the philosophy behind their work and why this recognition is a validation that young African architects are shaping global discourse.

Kindly introduce yourself and tell us about LondonConsult.

My name is Adrian Madoya. I'm a Kenyan self-taught architect with a deep passion for visualisation, graphic design and illustration.

I studied medicine after high school for about a year before switching paths. I joined the School of Architecture at the University of Nairobi but didn’t complete my studies. While I was still in school, I began receiving opportunities that aligned with my interests in architecture. I knew those opportunities wouldn’t last forever, so I leapt. That was in 2020, and since then, I’ve been in practice.

I'm currently the principal partner of a Nairobi-based studio called LondonConsult.

Let’s begin with your name, LondonConsult. It’s striking. What does it mean to you, and why did you choose it?

Exactly, it’s meant to provoke. People often ask, “Why London?” And I’m used to that. The name is intentional.

When I started the practice, I was about 24, and I noticed that in this market, the idea of luxury is often tied to the foreign. People want the BMWs, the Mercedes. “Maisha London,” you’ve probably heard that phrase. It means something elevated, something aspirational.

So, I chose the name ‘LondonConsult’ to play into that. I wanted a name that would open doors before I even walked into the room, a name that felt bigger than me. When I pitched to clients, I needed them to think, “This kid must be part of something global.” It gave the work an aura that made people pause.

But it’s not about the geography. It’s cultural. In Nairobi, when people say “Maisha ni London,” they’re referring to a kind of life or experience that feels refined or unfamiliar, and that’s exactly what I wanted our design work to evoke.

You mentioned you’re the principal partner. How many partners are in the team?

I'm the principal partner and creative director. My role is twofold: I handle conceptual design and I act as the bridge between clients and the design team. That includes understanding briefs and sketching out concepts.

We’re a team of eight consulting partners. For each project, we curate the team based on relevance. If we’re designing a hospital, we might bring in a nurse. If it’s a home for a footballer, we might consult a sports journalist. It’s always tailored.

Earlier, you mentioned that you treat small briefs with big ideas. Why is that important, especially in the African context?

We’re often mistaken for a studio that only handles high-budget clients, probably because our work looks expensive. But I always clarify: it's not about the money.

What matters to us is the vision. I’m very picky about the projects I take on. Beyond the client choosing us, we also assess the project internally. Is the client design-literate? Are they excited about doing something extraordinary, even on a tight budget?

Because for us, design isn’t just about delivering function, it's about pushing boundaries, even for our growth.

Let’s talk about Little Orbit. What was the core idea behind your design, conceptually, emotionally and spatially?

Little Orbit began when we came across an open competition online. It was for a rural nursery school. We had never designed a school before, and I saw it as a chance to align our vision with a new typology, something fresh yet personal.

The idea was deeply inspired by the two weeks I spent during the December holidays with my niece, Chloe. She’s four years old. It was the first time I’d had a child around me for that long. I was fully involved, from feeding her doll to roleplaying kitchen scenes. And I started to notice things.

Chloe was drawn to anything that matched her scale. She wouldn’t take tea unless it was in her small pink cup. She had this deep affection for her doll and would insist I babysit while she went to “work”. And she loved my architectural models, not because she knew what they were but because they looked like toys to her.

I realised: Children love objects and spaces that reflect their own proportions. That’s why they’re so drawn to toys, they are miniature versions of the adult world.

So when we started designing the school, I told my team, “This building has to relate to a child’s sense of scale, it should feel like it was built just for them.” But at the same time, it had to accommodate adult use, too.

In our first concept sketch, I drew a child on one side and an adult on the other. Then I connected their heads with a sloping line. That line became the guiding principle, a sectional flow from child to adult scale.

So in terms of form, the building became a concentric circle, but conceptually, it was more than that. In the section, it reads almost like a cell. It’s a structure that grows inward and outward at the same time, much like childhood itself.

And emotionally?

Emotionally, I’ve always believed that architecture should move you on first impression. The kind of building that makes you pause and wonder, “What could that be?”

I wanted Little Orbit to feel curious, to evoke that sense of wonder, especially for the children. It’s not what they expect a school to look like. That unfamiliarity sparks imagination. That’s the kind of architecture I care about.

You ended up getting a Special Mention from the jury, quite a big deal. What do you think earned that recognition, and what did it mean to you?

First of all, we did a nursery school in black and white. Who does that?

Most nursery schools go wild with colour, cartoon characters and alphabets on the wall. But I thought: why trivialise childhood architecture? Why not embed meaning in the form itself?

Our design was bold in its restraint. We said, this building should be powerful even if you strip away the colour. And I think that stood out.

This recognition, it meant everything. We’ve worked on many ambitious ideas, but most of them never make it to construction. Clients often back out at the last minute and say, “Let’s do something more normal.” This win validated our design instincts.

We’ve always believed bold ideas can be grounded, affordable and beautiful, and now the world is saying the same.

So just to clarify, your design was for a nursery school in Senegal, but it was conceived and developed in Nairobi. How did you approach working in a different African context?

Honestly, part of it was intentional for the longevity of our studio. I was tired of constantly being told to “be realistic”. So I decided to work with people who truly believed in bold ideas.

One of the biggest luxuries offered by this particular competition is that the winning design gets constructed. It’s not just theoretical recognition; it becomes real. That was a major motivation for us.

We knew that if our idea was appreciated in Senegal, perhaps people in Nairobi would also start to see its value. Sometimes it feels like we have to prove ourselves to the world before we’re accepted at home. And for us, that’s what this was, a way to say, “Look, our work can exist globally, LondonConsult can work anywhere as long as you’re brave enough to take on bold ideas.”

You spoke quite passionately about vernacular architecture and how it’s often led by foreign architects. What needs to change for African studios to take the lead in designing for African spaces?

That’s a real issue. Beyond just being led by outsiders, vernacular architecture is often misunderstood here. People associate it with poverty. It’s either seen as ultra-basic or ultra-luxury, there’s no middle ground.

Even in architecture school, we studied vernacular techniques, and I could see how thoughtful and sustainable they were. But I always asked myself: “Why does it have to look like this?” Because let’s be honest, people care about how things look. That’s why we buy iPhones or drive Benzes.

So I thought: What if we keep the ideas, the logic of vernacular architecture, but give it a contemporary face? That’s what I wanted to do, shift the narrative. You can be modern and still grounded in local wisdom.

We were given a budget of Sh10 million for the Little Orbit brief. And we said, “Even on that budget, this building can be extraordinary.” That’s what we wanted to prove, that vernacular doesn’t have to feel dated or cheap.

You indicated that this win should be a signal to institutions and clients to trust young African designers with serious briefs. What’s the biggest barrier to that trust right now?

People don’t trust novelty. They love it on the surface, they’ll admire bold concepts and say, “This is amazing.” But when it comes to actually building it? That’s when they get scared.

They want something they’ve seen before. Something they know will “work”. So even though we’re producing these big ideas, they rarely make it past the drawing board.

Most of our clients are in their 50s. That’s the demographic with the resources to fund architectural projects. But what we need now is a shift in mindset, clients willing to give us room to stand on our own. That’s how we grow, and that’s how we transform the landscape.

What advice would you give to a young African creative, someone with big ideas but constantly told to “scale down” or “be realistic”?

Don’t ever let that inner child die. They’ll try to make you “pragmatic”. I hate that word. But your perspective, your vision, that’s the most valuable thing you have.

Hold onto it. Ride it out. Even when people dismiss your ideas, show them why they matter. And prove it to yourself, too.

Look at some of the world’s greatest creatives, people thought they were delusional. But they believed. They created. And eventually, the world caught up.