The red, wooden post hammered into the ground near the Malagasy village of Ambohidava heralds a change that will alter life here forever.

Visiting on a gentle, sunny Thursday afternoon, the only things disturbing the 500 residents are the crowing of cockerels and the occasional rev of a motorbike engine.

But the peace and tranquillity of rural life could well be shattered.

If plans go ahead then in two years' time the village could be gone and in its place will be a two-lane toll road.

Currently Amboidava lies around a two-hour drive from the capital Antananarivo. But journey times could change as the planned highway linking the capital to Toamasina, the country's main port and second city, goes right through the village.

The red post marks the route for the new road.

The fast road is envisioned to transform Madagascar's economy but it will come at a cost to some.

The significance of the potential disruption on the villagers cannot be understated.

Neny Fara has lived in Ambohidava her entire life.

Now 70, she first started farming pineapples and rice with her family at the age of four. Her ancestors have farmed here for generations.

The first thing you notice about her is her smiling eyes.

A diminutive 1.5m (4ft 10in), she welcomes me into the house she shares with her husband Adrianavony and serves us a traditional Malagasy chicken and rice dish.

She has supported her family – including a son who cannot work due to living with mental health issues – with farming her whole life.

But now both her pineapple and rice fields lie in the way of the new road.

"It hurts me, I feel like I've been stabbed in the back," she says on a short but steep walk down to her rice paddy.

"It's hard because no-one has been in touch with us about the plan (for the highway). This is the land we have owned for generations. It's heartbreaking."

She also says that no compensation package has been agreed with the government. This is a claim that farmers repeatedly tell us as we travel around the area, but the authorities have pledged that compensation will be provided within a year of the road being built.

The first 8km (five miles) of the highway was officially opened by then-President Andriy Rajoelina - who commissioned the project - during a southern African regional summit in the country in August.

He was deposed in a coup in October, with the new government saying it will continue with the project.

Built by Egyptian construction company Sancrete, it will eventually stretch for some 260km and will cost around $4 (£2.90) for cars and $5 for lorries to use.

When it comes to funding the estimated $1bn project, a fifth will be coming from the state with the rest from outside sources, such as the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa.

The smooth tarmac and clear road markings of this first stretch certainly contrast with the unmarked, frequently potholed roads that make up much of Madagascar's transport network.

If you want to travel between Antananarivo and Toamasina currently, that involves taking what is called Route National 2.

Progress along it can be slow going, as the heavy traffic on the two-lane road squeezes through small towns and navigates around crevices in the road. Old women filling in potholes with dirt in exchange for tips from drivers can be seen.

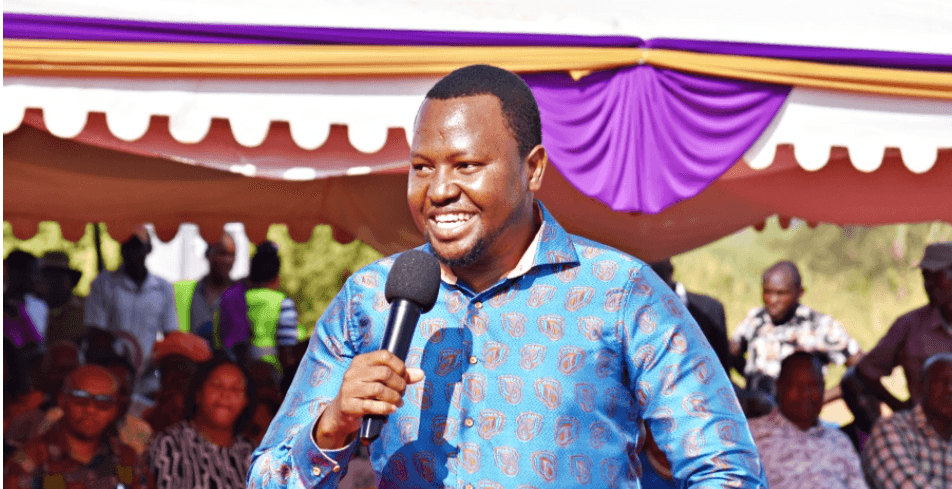

At a transport stop we meet 35-year-old Reka.

He has been driving this route in his lorry, carrying second-hand clothes, twice a week for the last nine years.

"It can take me up to 16 hours one way," he tells the BBC. The government says the new highway will reduce this travel time to three hours.

"The current road is very bad. It's really narrow and there's lots of trucks, which makes me worried. That's why our country needs to construct another road," he adds, before he continues his journey towards the coast.

According to government projections, the new road will lead to a tripling of activity at Toamasina port, as well as create jobs in service industries, such as hotels and petrol stations along the route.

It is also expected to help Madagascar to export more of its products, including its world-famous vanilla.

All of this could provide a badly needed boost to the economy in a country where the World Bank says three in four people live in poverty.

Sancrete also claim that the reduced journey times will help lower emissions by up to 30%.

Madagascar is incredibly biodiverse, with more than 80% of its fauna found nowhere else on earth.

Environmental campaigners had been concerned that the road would cut through some of the country's virgin rainforest, but the BBC has been told that this no longer will be the case. Instead, the route will now go through areas that had previously been cleared for other reasons such as farming.

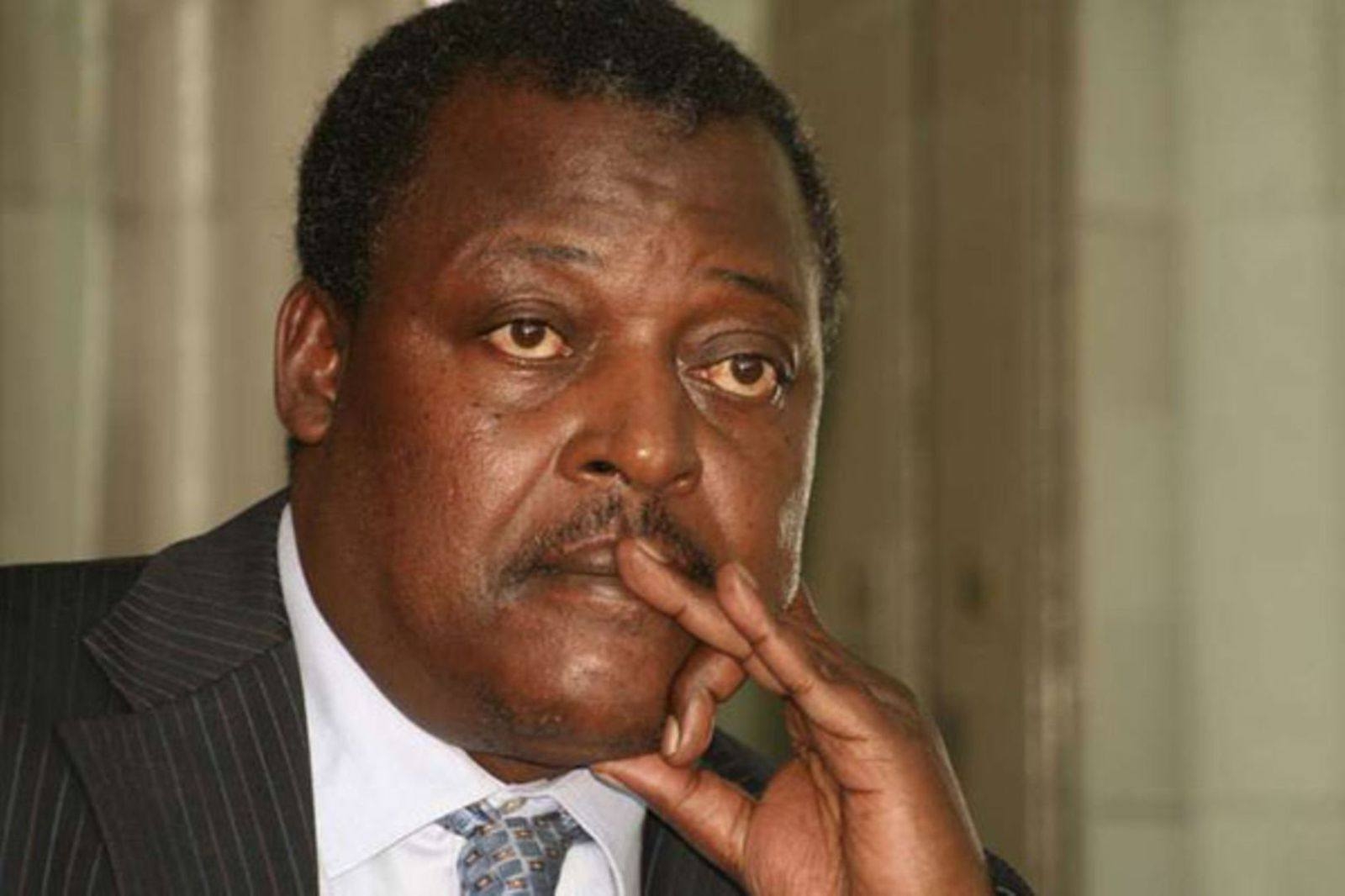

The environment minister at the time the highway construction started, 29-year-old Max Fontaine, told the BBC that the country was getting the balance of protecting its heritage and environment, with its economic development, right.

"The first thing I want to see in Madagascar is the development of the country," he said, speaking next the place where the new highway starts.

"The highway changes everything. For agriculture, for water, for transport, for everything. This highway will radically change the face of Madagascar."

He also said the government would provide compensation to those affected – within a year of the road being completed – and also formalise land ownership, which should prevent private companies and individuals grabbing land.

"We need to respect that if your ancestors have lived in a place for three generations then logically you are entitled to live in this place.

"The target is to do two million land titles and we have already completed 75% of this. It means that no-one can take your land as it is recognised on paper by the law."

Back in Amboidava, an impromptu village meeting is taking place on a path by the rice fields, chaired by Neny Fara.

People here are upset that the red posts seem to indicate that the road will go through ancestral graveyards, in a culture where honouring the dead is seen as essential.

The villagers defiantly vows to fight the highway.

"We should be giving respect to those who have died," Ms Fara tells the crowd.

Madagascar is not unique in facing the difficulties of balancing its development, with protecting its environment and its traditional culture.

But with construction firmly under way, it looks like the serenity enjoyed by locals in Amboidava will be irreversibly altered.