The Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa (AFSA), a continental network representing more than 200 million small-scale food producers, indigenous people, pastoralists, women, and youth, acknowledged the efforts of negotiators in Belém.

However, the network said the final COP30 outcome, known as the Mutirão, fell short of the ambition required to confront the climate crisis, particularly in relation to food systems and agriculture.

"Leaving agriculture and food systems out of COP30’s Mutirão decision is a missed opportunity. Climate action cannot succeed without addressing the realities faced by millions of small-scale farmers across Africa," AFSA said in a statement.

The Mutirão, named after a Brazilian Portuguese term for collective labour or community effort, was expected to reflect a unified global push toward climate solutions.

Yet AFSA noted the final text contains no references to food systems, agriculture, food security, or food production, sectors highly vulnerable to climate impacts and central to global greenhouse gas emissions.

Agriculture alone accounts for nearly a third of global emissions and remains a backbone for livelihoods in much of the global South.

Its omission, the group argues, weakens alignment between global climate goals and the realities of communities on the ground.

AFSA entered COP30 with clear priorities, including the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), the Sharm el-Sheikh Joint Work on Agriculture (SJWA), National Adaptation Plans (NAPs), Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC 3.0), the Just Transition Work Programme, and climate finance.

But the group observed several setbacks.

Agroecology, long championed by African producers as a climate-resilient farming approach, was not integrated into GGA indicators, limiting the ability to measure adaptation outcomes for soil health, biodiversity, and local food systems.

“When industrial agribusiness dominates the conversation, the voices of smallholder farmers, the backbone of our food systems, get drowned out.

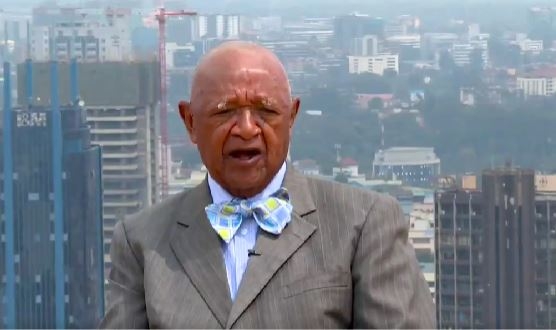

True climate solutions must start from the ground up," AFSA Climate Change and Agroecology Programme coordinator Simon Bukenya said.

Meanwhile, the SJWA remains without a defined institutional framework beyond 2026, leaving governance and long-term technical collaboration uncertain.

Nationally, many African countries have developed or submitted NAPs, but financing gaps, weak institutional support, and limited backing for locally led approaches remain unresolved.

COP30 did not secure grant-based funding to translate these commitments into action.

Similarly, guidance on incorporating food systems transformation or agroecology into NDCs was absent, and agriculture, the continent’s largest employment sector, was insufficiently addressed within the Just Transition Work Programme.

AFSA also raised concerns over stakeholder imbalances at COP30. Industrial agricultural interests dominated the Agrizone, promoting monocultures, genetically engineered seeds, and fossil fuel-dependent production models, while smallholder farmers, who feed over 60 per cent of the world’s population, remained underrepresented.

The network warned that this imbalance risks shaping climate discourse toward export-oriented and high-input technologies rather than addressing structural vulnerabilities in African food systems.

Looking ahead, AFSA reaffirmed its commitment to advocating for the integration of agroecology into global and national climate frameworks, ensuring accessible grant-based climate finance, and strengthening the participation of small-scale producers, Indigenous Peoples, women, and youth in UNFCCC processes.

The group also pledged to engage constructively ahead of COP31, with attention to GGA indicators, SJWA governance, NAP implementation, NDC submissions, and just transition mechanisms.

“Without explicit recognition of food systems and agriculture, the Mutirão represents an incomplete response to the climate crisis,” he said.

The network called on negotiators to rectify these gaps in upcoming talks, emphasising that food sovereignty, agroecology, and climate justice must be central to achieving the Paris Agreement goals.

As Africa faces rising climate risks, advocates insist that global food systems transformation is not optional; it is a prerequisite for meaningful climate action.