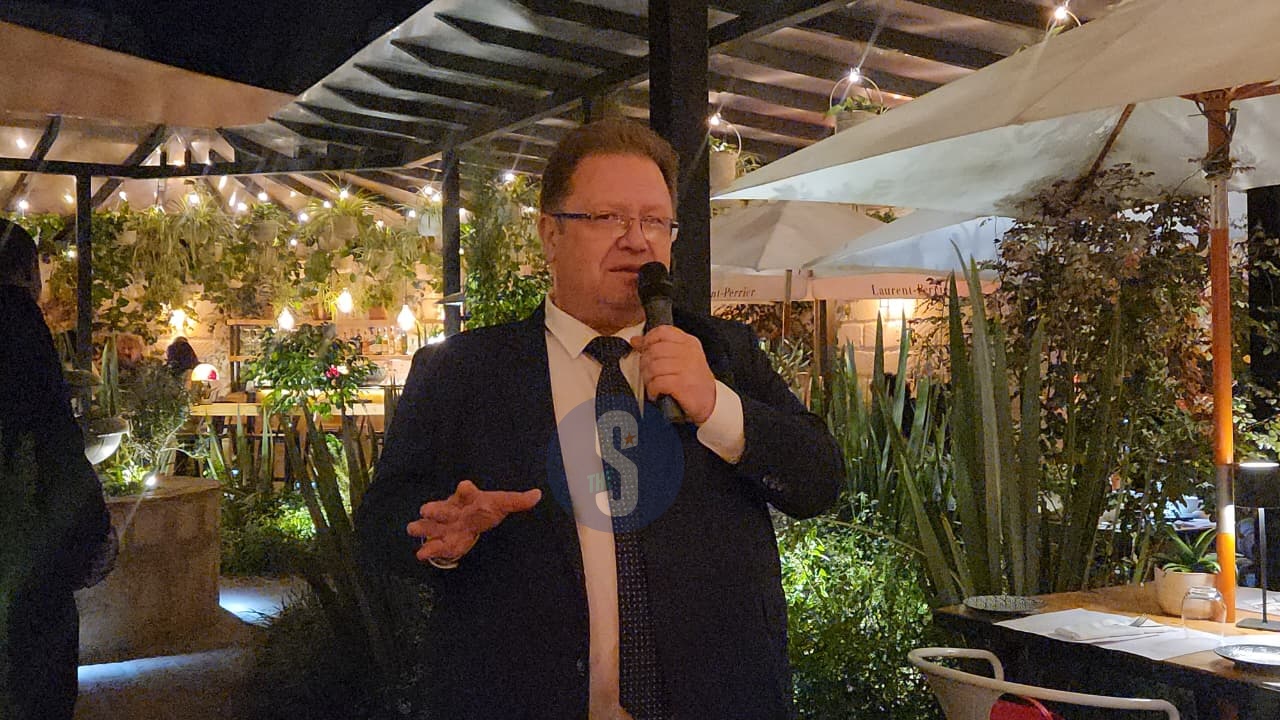

Russian Ambassador to Kenya Vsevolod Tkachenko during an exclusive wine tasting on November 28, 2025/ TRACY MUTHONI.

The Russian Federation is making a quiet but notable entrance into Kenya’s growing wine scene.

In a warm and engaging evening in Nairobi, Russia’s Ambassador to Kenya, Vsevolod Tkachenko, introduced local wine lovers, sommeliers, and industry observers to a selection of Russian wines opening a window into a young yet rapidly evolving industry that he believes carries valuable lessons for Kenya.

Ambassador Tkachenko, who has served in Kenya for a year and a half, used the exclusive wine tasting not only to showcase Russian viticulture but also to highlight how both history and modern innovation have shaped the country’s wine revival.

“I am happy to be here and even more happy to introduce some Russian wines to the Kenyan public and to the famous sommeliers of Nairobi,” he said, acknowledging with a laugh that the idea of Russian wine in Kenya might sound unexpected.

“Yes, I am surprised as well as you, because Russian wines in Kenya is something extraordinary.”

A long journey from Ancient Roots to Modern Revival.

Although the modern version of Russia’s wine sector is relatively young, the ambassador reminded guests that wine making in Russian territories has deep historical roots.

“Russian wine making has come a long and complicated way, from ancient traditions to its modern revival,” he said.

He traced the origins to the ancient Greek colonies on the Black Sea coast—areas such as Crimea and Taman where settlers discovered fertile soils, abundant sunshine, and sloping hills ideal for growing grapes.

It is along these shores, near the ancient city of Hersones (later known as Herson), that wine production began more than a thousand years ago.

The ambassador explained that wine has been produced “in the territory of modern Russia for more than a thousand years, since the ancient Greeks came to the shores of the Black Sea.”

Despite this historically rich background, Russia’s contemporary wine revival only began in earnest about three decades ago.

In that short time, the country has made notable progress in grape variety development, wine quality, and international recognition.

“Russian winemakers are producing various and interesting wines, as well as soft and sparkling, white and red and rose, as well as dessert wines,” he said.

Still, he acknowledged that Russian wines remain unfamiliar to many consumers globally, partly because they only recently entered the international market. “They are still considered new players,” he noted.

Indigenous grapes take centre stage.

One of the strongest messages the ambassador delivered was Russia’s commitment to working with indigenous grape varieties.

For him, these varieties are not simply agricultural products—they represent culture, identity, and terroir.

He pointed to Divnomorskaya Estate as an example of a winery staying true to local grapes.

“For me, the best one is the Divnomorskaya Estate. If I translate it, it is a ‘wonderful sea winery.’ They specialise in indigenous grapes from the Russian soil, not imported, not Pinotage, not Cabernet, but indigenous ones,” he said.

Such grapes, he explained, offer distinctive flavours shaped by Russia’s diverse landscape. They carry tones of fruits, dried fruits, and flowers aromas that cannot be found anywhere else.

“I can tell you a thousand words about them, but it's better to make one sip,” he said with a smile, encouraging guests to discover the flavours themselves.

His hands-on approach and insistence on tasting over talking underscored a key point: wine develops meaning only when experienced.

For Kenya’s budding wine producers who are exploring their own identity his message resonated strongly.

A new era for Russian wine making.

The ambassador provided extensive context about how Russia rebuilt its wine industry after the Soviet era.

Under Soviet rule, wine production was dominated by large state farms, research institutions, and extensive grape varieties.

But the focus, he said, was on quantity rather than terroir or style.

“During the Soviet era, the industry became widespread: large state farms, scientific research, and grape variety selection appeared. However, the main focus was on quantity rather than terroir and style,” he noted.

The 1990s brought what he described as a crisis, as the industry grappled with new economic realities.

However, the decades that followed ushered in significant revival driven by private wineries, international standards, and technological improvement.

In 2014, Russia introduced legal frameworks to protect wine origins through Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) and Protected Designation of Origin (PDO).

The 2019 Wine Law then established a comprehensive structure for the industry.

These reforms ushered in a new era one defined by quality, identity, sustainability, and international competitiveness.

For emerging wine regions like Kenya, these strategies offer a possible roadmap.

Russian Ambassador to Kenya Vsevolod Tkachenko during an exclusive wine tasting on November 28, 2025/ TRACY MUTHONI.

A diverse landscape of wine regions.

Russia’s wine industry is shaped by its varied geography. The ambassador highlighted several regions that play a crucial role in wine production.

Krasnodar Krai is the country’s largest wine-growing region, accounting for about 55 percent of vineyards.

It grows both international varieties; Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, and Merlot and indigenous varieties such as Krasnostop Zolotovsky and Sibirsky.

Crimea, which he called the historical centre of wine making, hosts vineyards that flourish in maritime climates. It produces internationally known grapes as well as indigenous ones like Kokur, Ekim Kara, and Kefesia.

The Don region in Rostov stands out for its strong identity and indigenous varieties such as Tsimlyansky Black and Plechistik.

Other regions, Dagestan, Stavropol, and the Lower Volga are also developing their own versions of Russian wine, experimenting with both local and international grapes.

“We have many new and promising wines in Russia,” he said, highlighting the importance of diversity, microclimates, and experimentation.

This regional variety, he emphasised, offers Kenya a striking lesson: no country needs to focus on a single grape variety or wine style.

Instead, success lies in understanding local soils, climates, and conditions and building identity from within.

Wine, tourism and cultural exchange.

Russian wine making today embraces a holistic approach that blends quality production, viticulture science, and wine tourism.

Wine estates in Russia are increasingly becoming tourist attractions, allowing visitors to pair tasting experiences with local culture and landscapes.

For Kenya, whose wine production remains largely concentrated in cooler highland areas such as Naivasha and parts of Rift Valley, this approach highlights the potential of building a tourism-driven wine economy.

The ambassador emphasised that Kenyan producers could adopt similar strategies to differentiate themselves and attract local consumers and international travellers.

“Russian wine making continues to develop its own style and strives to take its rightful place on the world wine map,” he said.

His hope, he added, is that introducing Russian wines to Kenyans will widen their appreciation of global wine cultures.

“I hope that today's event will help our Kenyan friends to taste the sun and fertile products of the sun and fertile soils of Russia,” he remarked.

Lessons Kenya can draw from Russia’s rise.

As the evening progressed, it became clear that the ambassador’s presentation was not just a tasting but it was a masterclass in how an emerging wine country can chart its rise.

“I know that you think Russia is famous only for growing vodka, but it's not so. For the last 30 years, we paid a lot of attention to the reviving wine making industry, bringing in new technologies, hundreds of new wineries emerged, and now they are producing many very interesting sorts of wines,” he said.

He underlined that Russia’s success stems from a blend of tradition, innovation, and protection of indigenous varieties elements that Kenya can easily adapt.

By preserving its own grapes, adopting international standards, investing in technology, and encouraging wine tourism, Kenya could accelerate the growth of its wine sector.

The ambassador invited guests to experience Russia’s indigenous wines firsthand.

“I decided to bring only autochthonous, autochthonous traps, wine made from autochthonous grapes. Therefore, it is for your judgement. I hope you will enjoy the evening,” he said.

With a light hearted touch, he concluded his remarks with a comment that brought laughter across the room.

“On a normal day, a couple of glasses will do for me of course. However over the weekend, four is not bad,” he said.

A toast to shared knowledge and future collaboration.

As the exclusive wine tasting drew to a close, guests lingered over their glasses, discovering the aromas and stories captured in each Russian bottle.

The ambassador encouraged them to savour each sip slowly, for each wine carried a piece of the land and the people who created it.

“I can tell you a thousand words about them, but it's better to make one sip,” he said echoing the same invitation with which he had begun.

Though Russian wines may be new to Kenya, the ambassador’s message was unmistakably clear: innovation, respect for tradition, and a firm commitment to quality can transform a young wine industry into a global contender.

For Kenya, an agricultural powerhouse with fertile soils, diverse microclimates, and a rising culture of wine appreciation, the lessons from Russia’s evolving wine sector arrive at a timely moment.

With the right investments, identity, and ambition, Kenya too can carve its place on the world’s wine map.