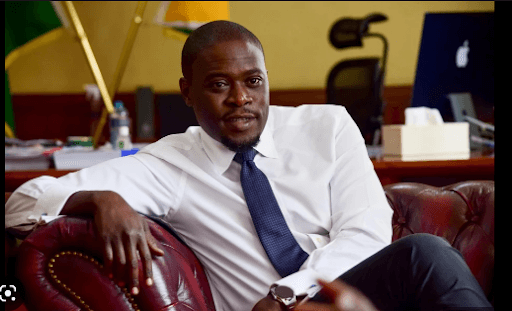

Law Society of Kenya (LSK) president Faith Odhiambo/FILE

Law Society of Kenya (LSK) president Faith Odhiambo/FILE

The appointment of Law Society of Kenya (LSK) president

Faith Odhiambo to President William Ruto’s compensation panel for victims of

protests and post-election violence has ignited a national debate that

continues to polarise opinion.

For many, Faith has long stood as a fearless defender of the

vulnerable, an advocate who has spoken out against police brutality, arbitrary

arrests, and alleged extrajudicial killings.

She has represented numerous victims of abductions and state

excesses, often on a pro bono basis, making her one of the most visible legal

voices for justice.

That background has prompted some to argue she is uniquely

positioned to serve on the panel.

Her lived experience with victims, they say, gives her the

credibility to influence how compensation will be structured and delivered.

Yet her decision has also triggered sharp criticism,

particularly from Kenyans sceptical of the current regime.

Detractors argue that by joining a panel constituted by

President Ruto, she risks legitimising the same government they believe bears

responsibility for the violence and deaths she has long condemned.

To them, her appointment represents a contradiction: the

activist-advocate now working under the very system she has opposed.

The panel, chaired by Prof. Makau Mutua, President Ruto’s

senior advisor on constitutional affairs and human rights, was sworn in

following Ruto’s August 8 proclamation announcing a framework for compensating

protest victims.

Faith serves as vice chairperson, while other members

include Kennedy N. Ogeto, Irungu Houghton, John Olukuru, Rev. Kennedy Barasa

Simiyu, Linda Musumba, Duncan Ojwang’, Naini Lankas, Francis Muraya, Juliet

Chepkemei, Pius Metto, Fatuma Kinsi Abass, and Raphael Anampiu.

Richard Barno has been appointed as Technical Lead, Duncan A. Okelo Ndeda as Co-Technical Lead, with Jerusah Mwaathime Michael and Raphael Ng’etich serving as Joint Secretaries.

Speaking at the swearing-in ceremony, Prof. Mutua emphasised that the panel would remain committed to creating a framework that provides clear guidelines on peaceful protests, underscoring its broader mandate beyond compensation.

Faith, however, has been quick to defend her decision in

light of the public uproar.

In a statement titled “Duty and Loyalty: A Call to Serve”,

she underscored that apart from the swearing-in, she has not participated in

any meetings or engagements with the panel.

“I respect the rule of law and abide by the orders given by

the High Court,” she stated, adding that her allegiance remains to the

Constitution, not to the government or the opposition.

She reiterated that her guiding principle is service to

Kenyans, particularly victims still waiting for justice.

Faith has made it clear that she will continue pressing for

accountability, including calling on the Office of the Director of Public

Prosecutions (ODPP) to drop trumped-up terrorism charges against peaceful

protesters and instead focus on prosecuting officers caught on camera using

excessive force.

She has also reaffirmed the LSK’s commitment to providing

pro bono services to victims of brutality across the country.

Her words reflect the delicate balancing act she now faces.

Even so, the backlash persists. Critics maintain that

participation in a government-led initiative risks compromising her

independence and the credibility of the office she holds.

They argue that whatever the intent, her association with

the panel could be used politically to neutralise dissenting voices.

Supporters, on the other hand, contend that her involvement

is pragmatic.

By being at the table, Faith has an opportunity to influence

policy and ensure that victims’ voices are heard in the compensation framework.

They dismiss the criticism as politically motivated,

emphasising that her track record as an advocate will not suddenly vanish

because of her new role.

This tension, between activists wary of co-optation and reformists who see value in institutional engagement, captures the complexity of Faith’s current position.

She is, in many ways, caught between a rock and a hard place. If she withdraws, some may see it as abandoning victims at a critical moment.

If she stays, she risks alienating those who view her independence as her strongest asset.

Her case raises a critical question about the role of professionals in politically charged spaces.

Can one serve within government frameworks while remaining true to activist ideals? Or does such participation inevitably erode credibility?

For Faith, the answer will depend less on what she says and more on what she does in the coming months.

Ultimately, her appointment to the compensation panel reflects the paradox of public service in Kenya’s polarised landscape.

Faith’s decision to serve may be seen by some as a compromise, while others view it as a patriotic duty.

But what is clear is that she has entered a space where every step will be scrutinised, every action weighed against her past advocacy.

In this, she embodies the dilemma of principled leadership in times of division; standing at the crossroads of duty, loyalty, and public perception.