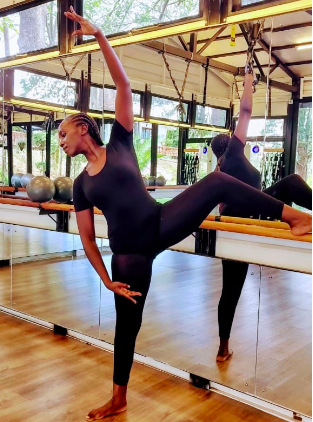

It was a dislocated knee, torn meniscus and fractured femur that changed everything. Lucy Mwai hadn’t planned to start a dance class that day. She’d only intended to stretch, maybe move gently to music, trying to ease the tightness in her body from an old ballet strain. But when a few of her friends joined her on the studio floor, something shifted.

They moved, breathed, and laughed together. It was casual. Healing. Freeing. “That was the beginning of the wellness dance class,” Lucy recalls. “It wasn’t formal at all. We were just listening to our bodies. And afterwards, everyone said, ‘We needed that.’” That accidental session became a weekly ritual, and eventually, a signature part of Lucy’s teaching practice.

But it also marked a deeper turning point: the moment she realised that dance wasn’t just her passion. It was a way to help people reconnect to themselves, body and soul.

THE MEDICAL STINT

Pliés and pirouettes are not all that took center stage. Lucy has been deep in the world of science. She studied Medical Laboratory Sciences at the Jomo Kenyatta University (JKUAT), driven by a desire to contribute meaningfully to healthcare in Kenya.

Like many young students, she imagined herself playing a part in fixing a broken system, working in diagnostics, improving patient care, and making a difference from behind the scenes.

“I wanted to venture into haematology or forensics. There was just something about going to a crime scene,” Lucy says while smiling. “I wanted to be one of the people who helped find the cure for cancer as a haematologist. For forensics, I found it extremely intriguing to go to a crime scene and figure out what exactly happened there. And because we did medical forensics, I could go ahead and major in that.”

Lucy says her medical course was meant to turn her into a researcher, one who fully understands the functioning of the body, who can work towards finding cures of diseases.

“I was also very passionate about that because science was beautiful. So, I found both art and science beautiful. When I was young, I would go to the kitchen and mix tea leaves and salt in a bid to experiment. And when my mum asked, no one, including me, would own up,” she says.

She says, after her university studies, which she completed and passed, the medical laboratory technicians and technologists board took the University students through rigorous exams before they could be issued the board certificate.

“And I'm not, and I will not shy away from saying that there was plenty of corruption in that process. It became common knowledge that, regardless of performance, if you did not pay up a little money to the right people, you would not get certified and you would not get your certificate,” she said.

Lucy says that, being a believer in no bribes, she was unable to get her certificate to practice.

“And that is why I never ended up practising through formal employment. I volunteered my services in laboratories while doing exams for like three or four years in a row and failing each time, without understanding the language of the board. To be honest, I didn't understand that all I needed to do was part with a few shillings,” she says.

During her college days, Lucy used to attend Ballet classes and also just have some fun to help her move her body. “It was something I was already doing ever since I was young, about 4 years. So, it is your after-school kind of thing. Like going for football after class. A hobby you love. That is what this was to me,” she said.

“But I then realised that Ballet had turned into my passion and I wanted others to learn it as well. I started wanting to teach people. I pursued further training abroad.”

THE RETURN OF BALLET

Lucy had danced as a child, captivated by the discipline and beauty of ballet. But it had always seemed like a hobby—something separate from her “real” life, from the future she was told to build.

As her frustration with the healthcare system grew, ballet slowly crept back in, first as an escape, then as something more.

“It felt like I was finally doing something with integrity. Something that didn’t require me to look away from harm, or participate in it.”

After a trip to South Africa in one of her summer holidays in 2015, Lucy returned with a new goal for her childhood love: ballet. “I came back, and after being encouraged by my ballet maestro, I started charging a little money for transport, like Sh200 or Sh300. I had been teaching since 2010, but never charged a dime. Since my fellow Kenyans did not know of ballet, most were not interested in taking it up,” she says.

“I found myself teaching more in the home of experts. Bringing the Majority of my clients, to say 95 per cent, experts. The shows I've thrown have a large majority of experts, who understand what ballet is, its importance, and the opportunities it can create.” Instead of focusing only on technique, Lucy built her classes around accessibility, community, and healing.

Her studio, she says, is more than a dance space. It’s a refuge. “We don’t just train dancers. We nurture humans,” she says. “Kids can have a lot of emotional distress. Home and school may be challenging, and life can be hard for them. But here, they can breathe.” And it’s not just children.

The wellness dance classes that began with her torn knee meniscus have become a lifeline for working women journalists, teachers, NGO workers who carry the weight of burnout and expectation.

“We stretch. We release. We move with intention,” Lucy explains. “It’s not about performing. It’s about presence. It’s about coming back to your own body.” She smiles as she talks about a childhood memory.

During one of her dad’s visits with his friends from London, she started twirling in the living area. “I just started twirling, and I just listened to the music. Of course, I was chased away because I was misbehaving in front of guests. I was chased away for twirling a little bit, lifting my legs. Because traditionally, girls would not just lift their legs,” she says.

But what helped Lucy was that her father, who was a lover of classical music, was very liberal and open-minded. Lucy is the first to admit that ballet is not always seen as “for us” in Kenya. It’s still viewed as elite, foreign, and even frivolous.

“But movement is universal,” she says. “And the discipline of ballet, its structure, its grace can be a form of resistance. It teaches you to stand tall, to take up space, to claim your rhythm.”

SCHOOL CHILDREN NOT LEFT BEHIND - MY LITTLE DANCER

Lucy says she started going to local schools and also writing proposals to entice the schools to have ballet as a co-curriculum. “I started aggressively trying to get into our local schools. But of course, since I was committed to it full time, I was now trying to find a balance between sustaining myself and wanting other people to learn about the art,” she says.

This made her register her company - My Little Dancer Services Limited. But she did it because she was very, very passionate about wanting Kenyans know that they too can learn and dance Ballet.

“I wanted the ideology and company to live beyond me. It is not in my name. The company is, it's not called Lucy's Ballet Studio because I didn't want it to, I wanted it to transcend me. “

She started by training the younger children because the older ones already had other priorities. For her proposal writing to schools, Lucy says that she had to put more effort and not just writing on paper and passing it to institutions.

“It doesn't matter how many proposals you write. Sometimes you can't get past the gate,” she says. She says ballet dance is not a mainstream activity but a voluntary co-curriculum. “For the parents who feel that they would like their children to learn classical ballet, or another activity, they sign them up at a small fee,” she says.

Lucy says her love for the arts made her begin an art program, adding that ‘art cannot be done in isolation’ “We started teaching Arts. Part of the heart of My Little Dancer is to bring on board other creatives who don’t fit in the mainstream. I went on a hunt for artists, qualified local artists, who want to grow and want a space and opportunity to train in fine arts and even drawing,” she says.

In her Little Dancer studio, Lucy and her team train dance, and arts in terms of drawing and painting “Our programs are very interactive, very fun-based, because children learn through fun activities. Our classes are progressive and repetitive, to allow development of Muscle memory,” she says.

She notes that when you begin to learn ballet, one cannot do one session. “For you to remember ballet steps, you have to train over and over.”

BIRTH OF DANCE FOR WELLNESS

Three years ago, a sudden injury changed everything for Lucy Mwai and gave rise to a new philosophy of movement. “I was teaching on a Saturday morning, in someone’s attic,” she recalls.

“Nothing intense, I just demonstrated a move.. I bent my knees, and they popped out of place. My body fell apart.” At first, she didn’t fully understand what had happened. The pain was sharp, disorienting. A dancer all her life, Lucy had pushed through aches before. But this was different. “I didn’t know my body was crumbling until it did,” she says.

“And for someone whose livelihood depends on movement, that kind of breakdown messes with your head.” When Lucy arrived at the hospital, the injury was so severe that the attending doctor asked her a haunting question: Was this a suicide attempt? “My body had been crying for help long before that day,” she says.

“But I brushed it off. I thought I was just tired.” What followed was the most physically and emotionally painful period of her life. But it was also the start of something transformative.

During rehabilitation, Lucy worked with a physiotherapist who not only helped her rehabilitate her body but also helped her understand the connection between pain, silence, and healing.

“He didn’t just treat my injury. He talked to me,” she says. “He made space for everything I was carrying physically and emotionally.” Overcoming that experience gave her a sense of getting a second chance at life. She wanted to give back to the community, and this planted the seed for what would become her Dance for Wellness program.

An initiative that uses intentional movement to support mental health, especially for people who live in high-stress environments or carry invisible burdens.

As Lucy recovered, friends would drop by her house. They brought food, laughter, and company. She noticed how community and conversation became just as essential to her healing as physiotherapy. The loneliness that had started to creep in began to recede.

“You can have all the money in the world,” she says, “but if you’re going through something alone, it’s easy to crumble.”

When she returned to teaching, she brought these insights with her. Her new classes weren’t just about steps or choreography, they were about connection, storytelling, and care. “Movement is a conversation,” Lucy explains.

“When someone starts dancing, even in the smallest way, they’re telling you something about how they’re feeling, whether they know it or not.”

She weaves storytelling into her sessions, encouraging dancers to tune into their emotional state. Some classes start slowly and heavily, reflecting anxiety or fatigue in the dancer. But this quickly shifts into joy, brightness, and release.

“The body remembers everything,” she says. “And once you start to move, you start to release. Your mood lifts due to the feel-good hormones that are released in your bloodstream, at times you don’t even realise it.”

Lucy believes that dance, when done intentionally, can be a powerful tool for mental clarity. She’s seen firsthand how a simple class can break through a fog of depression or anxiety.

“In those moments of movement, your focus changes,” she says. “It’s no longer about your problems. It’s about rhythm, breath, and presence. You start to see things again, literally. Colour comes back. Perception softens.” That brief separation from immediate problems, she says, is often the beginning of healing. “Wellness isn't just about the dance,” Lucy explains.

“It’s about what dance opens up for you emotionally, mentally, spiritually.” As she prepares to formally launch the Dance for Wellness program in May, Lucy is building in mental health support as a core pillar. There will be sessions guided not just by dancers, but by counsellors, clinical nutritionists and physiotherapists. The goal is to create a holistic space for healing, one that recognises how deeply movement and mental health are connected. “It’s not just about feeling good,” she says.

“It’s about finally coming home to yourself.”