The politicians were responding to questions about “abductions”, of course. Many people have expressed their disgust and anger at the way in which politicians responded to the desperation of Kenyans, including the parents of those who seemed to have disappeared, by wittering on about young people being undisciplined and even uncivilised, especially in their use of social media, and blaming their parents for this.

We have heard or read of people saying things such as, “We must respect the office of the President. Or human rights must “not be used against the public interest.”.

The politicians were not being stupid. Apart from their sycophancy, echoing what the President said, their reasoning was: Let’s talk about morality, and people will forget about the gross breaches of the law (not to mention morality) that are being complained about.

Indeed, a bit of a gut reaction to rhetoric about the need for morality and respect among the young might lead to some members of the public to be distracted from the real issues.

I want to take a slightly broader approach and reflect on what this reaction by politicians shows us about the respect for human rights, and law, in certain quarters.

POLITICIANS AND HUMAN RIGHTS

Politicians don’t have to worry much about their human rights. They get what they want—generous financial benefits, the right to say just what they like, especially in Parliament, a good chance of getting away with things they do wrong.

They don’t really have to worry about their right to freedom of speech, to a fair trial, nor to housing, food, water and education. This is true so long as they stay in favour – which is one reason why so many of them desperately want to be on, or close to, the winning side.

Politicians didn’t focus much on the Bill of Rights during the Constitution process—except for things that aroused particular emotions, such as abortion and gay rights.

This is one reason why we managed to get such a good Bill of Rights. But politicians may get really worried about citizens insisting on their human rights.

They want people to believe that good things flow from the generosity of their “leaders”, and not because they have rights. As a student, I found this insightful statement: “Charity honours the giver but humiliates the recipient.” The leaders want to be honoured.

Freedom of expression is one that bothers them most (along with freedoms of association and assembly, which are also about expression).

It is often called the “first freedom"—it" has been insisted on for millennia; it is the first in the US Constitution and is the freedom needed to assert all other freedoms. It is the freedom that exposes public figures to public scrutiny, which is why they don’t like it.

THREAT TO HUMAN RIGHTS

Rights are only important when people affected don’t like the way they are used. It is then that rights need respect and protection. People need to understand when rights may legitimately be limited.

The Constitution has a rigorous way to decide—ultimately by the courts—whether a human right has been effectively limited by law, but politicians are totally ignoring this and setting themselves up as the deciders on the limits on rights and what the consequences may be.

The first requirement for a valid limit on rights is that it must be in law. Freedom of expression is not limited by any law that says you must be “civilised”, or not be rude about the President. Yes, there are limits—most notably under the Cyber Crimes Act. We can’t go into detail here.

Some of the offences under that Act have been held unconstitutional by the courts and others ought to be held unconstitutional. We do not have a provision quite like that in Uganda: an offence “write, send, or share any information through a computer, which is likely to ridicule, degrade, or demean another person, group of persons, a tribe, an ethnicity, a religion, or gender.”

That has been used to convict a Ugandan Tiktoker for insulting the President. But the important thing is that the way to restrict expression constitutionally is to bring cases under this (or some other) Act), or perhaps an action for damages.

Because of how this has been totally ignored in the recent statements, I say that there is risk to human rights generally.

RIGHTS AND ABDUCTIONS

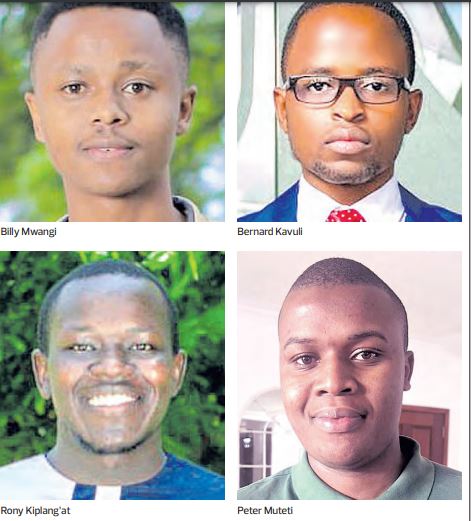

The recent complaints are about mostly young men being bundled into cars (with lying number plates) by people whose identity is concealed and driven away—maybe to be released later, maybe not.

Clearly there is a violation of the rights of abductees. Article 29 says that no one can be deprived of freedom “arbitrarily or without just cause”, detained without trial, tortured, or treated in a cruel, inhuman, or degrading way.

This last type of treatment, and torture, can never be allowed (Art. 25 ). And any law that allows any state officer to deprive anyone of liberty must meet the criteria of Article 24.

The first requirement—as mentioned earlier—is that such power must be given by law. There is no power to “abduct’ people. Yes, there are times when liberty can be taken away.

Most relevant is the possibility of arrest. The requirements for a valid arrest are strict. The person must be suspected of having committed a crime.

They must be told they are being arrested. And under the Constitution, they must be told “promptly” why (Art. 49 ). If they are not told they are being arrested, how can they be accused of resisting arrest? They are only supposed to be touched, not grabbed (unless they try to run away). Any force used must be no more than necessary.

Once arrested, they must be taken straight away to a police station. And then to a court to be charged within 24 hours—unless a weekend intervenes.

RULE OF LAW

We are not witnessing just a rubbishing of human rights. As the media have pointed out, the issue here is wider—it is part of a trend to ignore the rule of law.

The Penal Code deals with abduction: “Any person who by force compels, or by any deceitful means induces, any person to go from any place is said to abduct that person” (Section 256 ).

The penalty varies according to the purpose of abduction. Abducting someone so that they may be murdered can be punished by as long as 10 years in prison.

This seems mild; certainly if the abductee is murdered, I would think there should be a prosecution for “aiding and abetting” murder, which carries the same sentence as actually killing, namely, a maximum of death.

Let it be perfectly clear: there is no way it can be legal for any person in this country to abduct another person—unless what they are doing is to arrest them using legal powers to do so.

Even if the person doing the “abducting” is a public servant, even a member of the security services. (It might be legitimate, for example, to remove unwilling people forcibly from a flood-risk zone or some other situation of necessity, and, of course, war is different.)

In fact, what we have witnessed

from those politicians is not just a

willingness to control without law,

it is a willingness to control by the

commission of crime, by condoning

crime or by threatening criminal actions—and – and instilling fear.