A women fills her daughter's dish with water during a dry season in Kenya. The next drought will inevitably come, which is beyond our control.

A women fills her daughter's dish with water during a dry season in Kenya. The next drought will inevitably come, which is beyond our control.

We often discuss the physical effects of climate change, such as flooded roads, withered crops, and empty dams. However, we frequently overlook its impact on mental health, particularly for individuals already living on the margins of society.

In a new study published in eBioMedicine, our team at the Aga Khan University’s Brain and Mind Institute examined the effects of climate shocks, like droughts, heatwaves, and failed rains, on the mental health of women in rural Kenya. The evidence was striking. We found clear, measurable links between extreme weather events and increased levels of depression and suicidal thoughts among women in Kilifi County, a region where most families depend on small-scale farming and are heavily reliant on the weather.

Women living in informal settlements were particularly vulnerable. Compared to those from more stable rural households, they were significantly more likely to experience psychological distress after climate-related events. For instance, when rainfall was low, reports of suicidal thoughts rose by nearly 30 percent. When rising food prices were factored in, that figure increased even further.

These statistics reflect the daily struggles of women who wake up wondering how they will feed their families, when the next rain will arrive, and how to manage their limited resources. Many are quietly crumbling under this pressure, with little support available. Mental health services are scarce in these areas, and there is still a strong stigma surrounding the seeking of help.

What makes this research notable is that we were able to demonstrate, with robust data, that these mental health struggles are not just coinciding with climate events; they are directly caused by them. This is one of the first studies in Africa to clearly establish the causal connection. It confirms what we have long suspected: climate change is not only an environmental issue but also a public health concern. Mental health must be included in this conversation.

So, what can we do moving forward?

First, we need to ensure that mental health is integrated into every climate resilience plan. This includes training community health workers to recognize signs of distress, providing safe and accessible mental health services where people live and work, and collaborating closely with local leaders, especially women, to design solutions that fit their communities.

Second, we must take this issue seriously at the policy level. As Kenya adapts to climate change, mental health should be prioritized alongside food security, water access, and economic development. These issues are deeply interconnected.

Finally, we need to continue listening. The women in our study are not merely research subjects; they are voices that can help us understand the lived experience of the climate crisis. By ignoring their experiences, we risk overlooking one of the most urgent challenges of our time.

The next drought will inevitably come, which is beyond

our control. However, we can choose how we respond. We can decide whether to

keep mental health invisible or treat it as essential to the well-being of

every community, particularly those most affected by climate change.

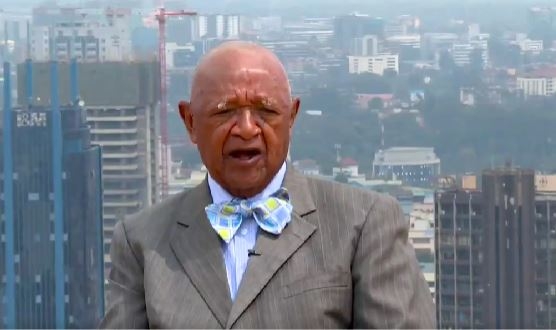

Prof Cyprian Mostert (pictured) is the Brain Health Economics Lead at the Brain and Mind Institute at Aga Khan University. He was the lead author of this recent study on The impact of climate shocks exposure to depressive and suicidal ideations among female population in Kilifi rural areas, Kenya - ScienceDirect published in eBioMedicine.