In the heart of Nairobi’s sprawling slums – Mathare, Korogocho and Mukuru – there exists a generation of boys whose lives once depended on scavenging the toxic, refuse-choked waters of the Nairobi River.

Armed with sacks and hooked metal rods, they waded knee-deep into the city’s sewage-laced artery, fishing out scraps of metal, plastic and even rotting electronics to sell for a few shillings – until the river-cleaning exercise started.

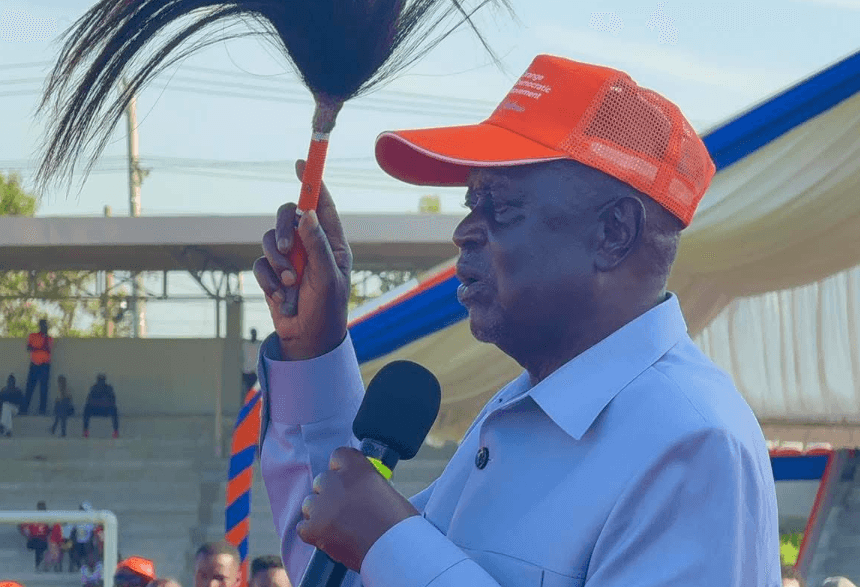

When President William Ruto’s ambitious Nairobi River Commission project was launched, the young men thought it would offer them new opportunities, but their hopes have been on a consistent nosedive.

The cleanup, while critical for the city’s health, has unintentionally destroyed the fragile ecosystem that sustains hundreds of these boys – some as young as nine.

“I used to make Sh200 a day,” says 16-year-old BO from Korogocho, his palms calloused from years of digging through debris.

“It wasn’t much, but at least I could eat. Now, I just roam.”

Without access to school, vocational training or stable family environments, many of them have been pushed further to the edge.

Some have turned to petty crime – phone snatching, drug-peddling and even joining gangs that promise fast money and protection.

JM, a 19-year-old from Mathare, now spends most nights ducking police patrols after being accused of theft.

“I never wanted this,” he says, staring blankly at the muddy trail beside the newly cleared riverbank.

“But when you’re hungry and there’s no one to help, you do what you must.”

Local elders and community workers say they warned government officials of this outcome when the cleanup plans were unveiled.

“We begged them to consider alternatives – skills training, even small jobs for these boys during the cleanup as a way of rehabilitating these young boys who have only become more deviant and a terror to the communities here,” says Mama Mercy, a youth mentor in Mathare.

“But no one listened. Now we’re seeing the consequences.”

The Nairobi River once symbolised death. Its waters were blackened by industrial waste and its banks lined with makeshift dumpsites.

Ironically, it was this very filth that gave the boys purpose.

For years, they risked disease, injury and stigma just to scavenge a meal out of it..

Now, with the toxic sludge gone and security guards patrolling the riverbanks, the silence is deafening.

Activists are calling for urgent interventions, including re-integration programmes tailored to the needs of these displaced youth.

“You cannot erase a slum economy without replacing it,” says Kevin Maina of the Nairobi Urban Justice Network.

“If the President wants a clean river, he must also care for the people who lived by it.”

Meanwhile, the boys navigate a new kind of darkness – one not of dirty waters, but of hopelessness. For some, crime offers the only escape from hunger and invisibility. For others, addiction has become a new river to drown in.

Back in Korogocho, BO still visits the riverbank where he used to scavenge.

“I don’t want to be a thief,” he whispers. “I just want a way out.”

Until then, the river runs clean – but the streets above it run with stories no one wants to tell.