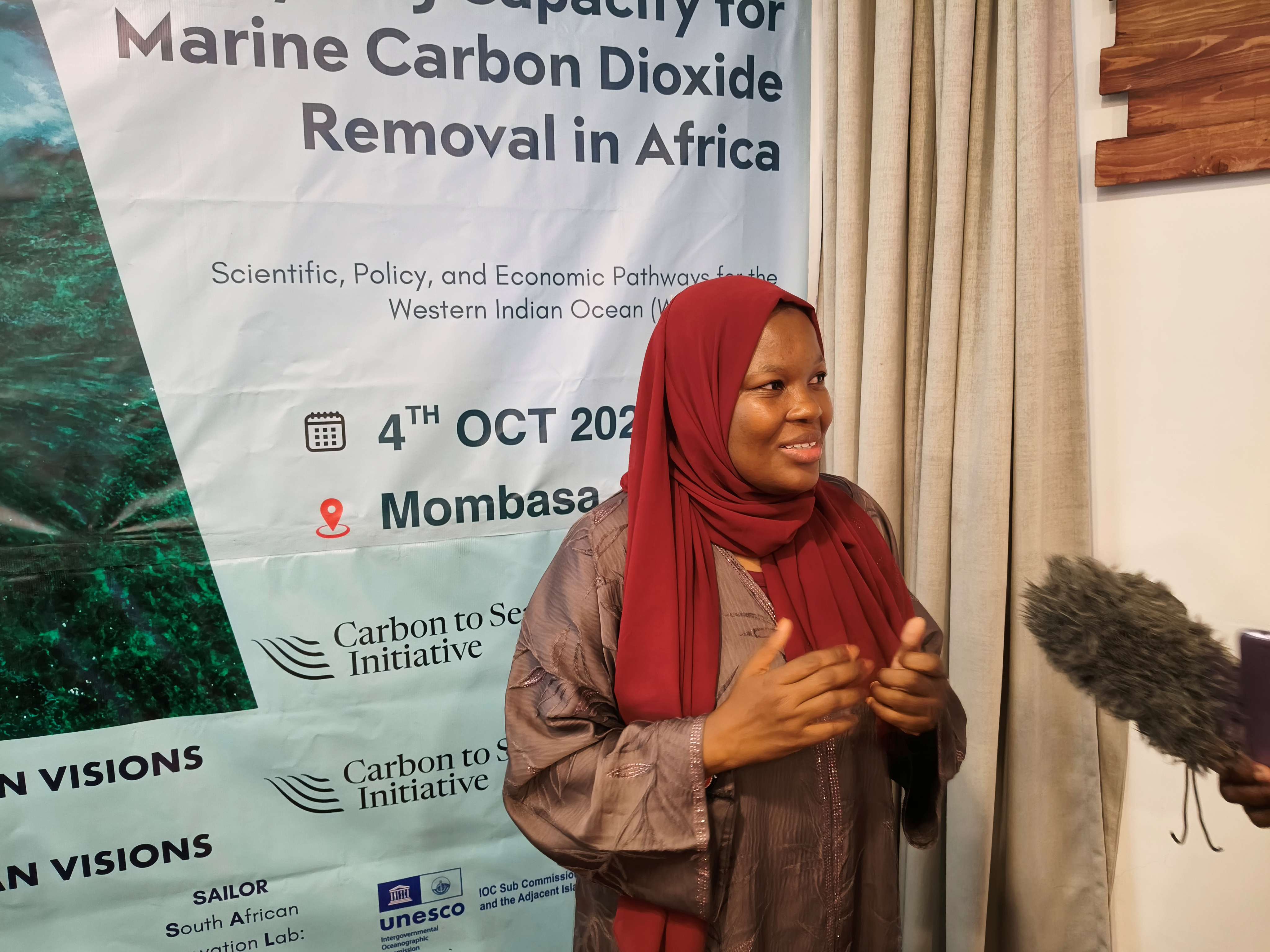

Ocean Climate Innovation Hub Kenya lead Mariam

Swaleh in Mombasa in Saturday / BRIAN OTIENO

Ocean Climate Innovation Hub Kenya lead Mariam

Swaleh in Mombasa in Saturday / BRIAN OTIENO Ocean Climate Innovation Hub Tanzania lead Shamim

Wasinyanda in Mombasa in Saturday / BRIAN OTIENO

Ocean Climate Innovation Hub Tanzania lead Shamim

Wasinyanda in Mombasa in Saturday / BRIAN OTIENOAfrica lacks the capacity to remove carbon dioxide from its marine ecosystems, despite being among the regions hardest hit by global pollution, scientists have said.

Experts meeting in Mombasa for the

Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal (MCDR) in Africa forum warned that while the

continent’s oceans absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide, few technologies

exist locally to remove it.

Delegates from Kenya, Tanzania,

Ghana, Nigeria, Madagascar and other African nations joined global experts to

discuss ways of advancing marine carbon dioxide removal.

Currently, most African nations rely

on natural carbon sinks such as seagrass and mangrove forests—methods that

are far slower than the pace at which oceans absorb carbon.

“This continent has been a receiver of technology for too long,” said Shamim Wasinyanda of the Ocean Climate Innovation Hub in Tanzania.

“As youth, we want to develop our own ocean

technologies that meet Africa’s needs.”

She said modern techniques such as ocean alkalinity enhancement, direct ocean capture and rock weathering could help the

continent reduce oceanic carbon dioxide and boost marine biodiversity—but

they remain inaccessible.

Removing carbon from the ocean,

Wasinyanda said, would help restore fish populations and sustain coastal

livelihoods threatened by warming seas. However, she warned that MCDR

technologies also pose ecological risks, including altered nutrient levels,

potential harm to marine species and challenges in verifying results.

Technical University of Mombasa researcher Mariam Swaleh, who leads the Ocean Climate Innovation Hub Kenya, said rising ocean temperatures have disrupted marine life and local economies.

“When the ocean chokes, people who depend on it also choke,” she said.

“Fish migrate to cooler waters, leaving African fishermen with little to catch.”

Matt Long, an American scientist with the non-profit Seaworthy, said the world cannot meet its climate goals by reducing emissions alone.

“We must also actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and the ocean,”

he said, noting that humanity emits about 40 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide

annually.

Long said Africa, though

contributing little to global emissions, could benefit economically by

developing MCDR projects—but only if scientific, policy and governance

frameworks allow local communities to share in the gains.

“The time is now to build the scientific and policy capacity to implement these technologies,” he said. “They will be urgently needed in the next 20 to 30 years.”