Experts taking soil samples from the field in Kisumu County.

Experts taking soil samples from the field in Kisumu County.  Dr. Manoj Kaushal, a Soil Scientist at the Alliance of

Bioversity International and CIAT.

Dr. Manoj Kaushal, a Soil Scientist at the Alliance of

Bioversity International and CIAT. Healthy soils are key to ensuring food security, sustainable livelihoods, environmental conservation and resilience to climate change.

However, the well-being of soils is often ignored and fertility levels decline over the years, resulting in poor crop yields.

Over time, soils, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, have been

degraded by overuse of synthetic farm inputs, erosion and overcultivation.

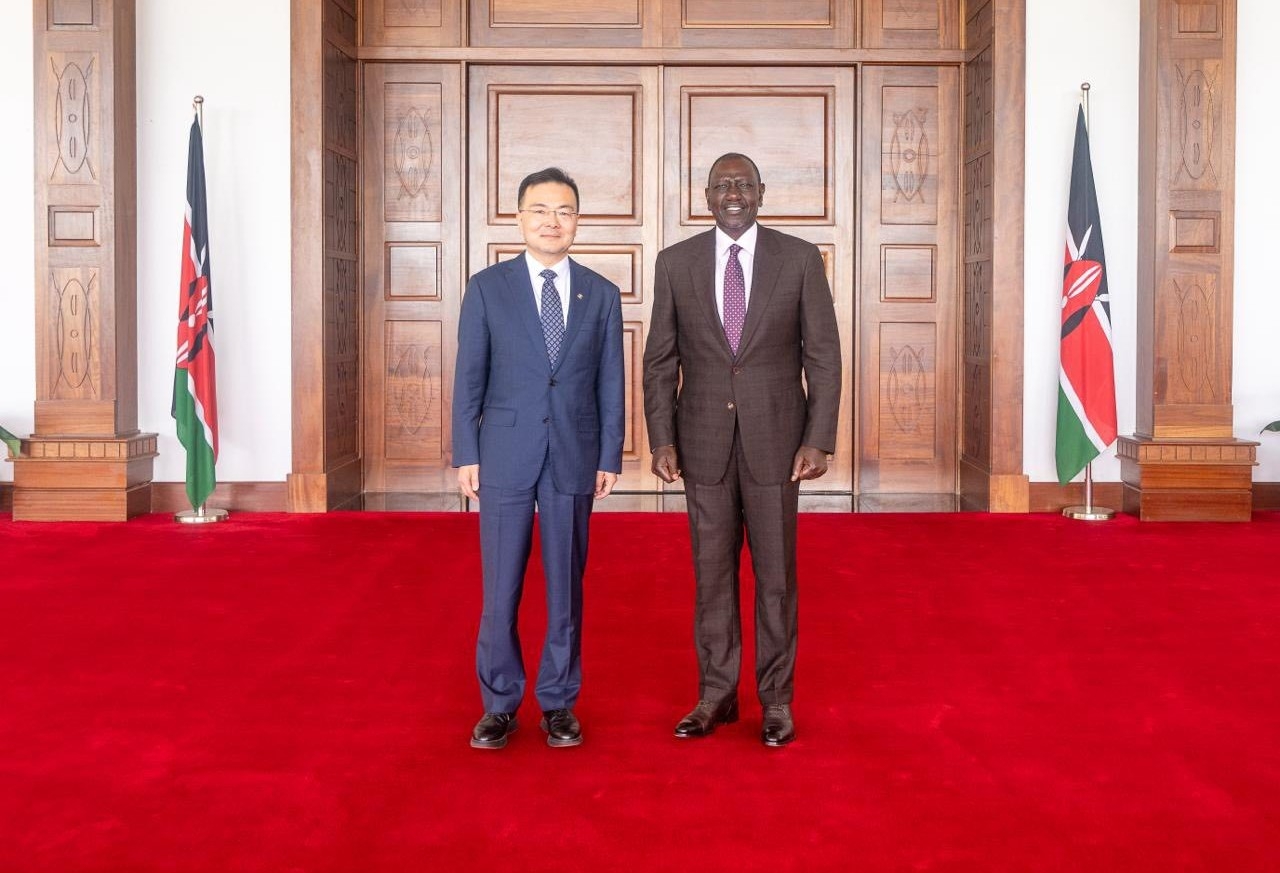

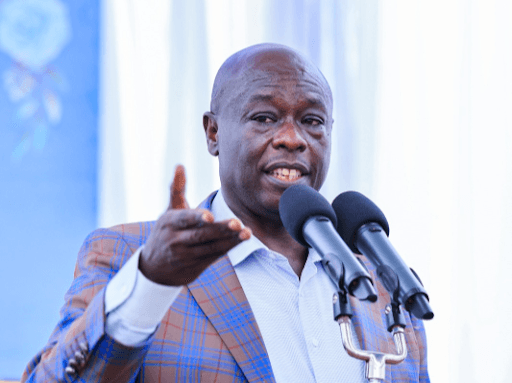

To unpack the significance of soil health and what it means for smallholder farmers, the Star spoke with Dr Manoj Kaushal, a soil scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International and the International Center for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT).

Excerpts:

In simple terms, how do you define soil health and what are the indicators of healthy soils?

Soil health is the ability of the soil to function optimally to sustain plants, animals, humans and the ecosystem. Healthy soils are rich in organic matter and microorganisms and can retain moisture and nutrients. They effectively support plant growth and withstand extreme weather conditions, especially following climate change events [such as droughts and flooding]. Essentially, healthy soil is alive, and when this is the case, communities thrive.

Why is soil

health so important, especially in Kenya and across Africa?

Kenya, like much of sub-Saharan Africa, has some of the most degraded soils. This is largely due to overcultivation, deforestation, overgrazing, excessive use of synthetic inputs [fertilisers, fungicides, pesticides], poor land management and climate change. These factors have deprived soils of essential nutrients, as reflected in declining crop yields, increased dependency on fertilisers and heightened vulnerability to extreme weather conditions.

What are some

simple, practical actions farmers can take to keep their soils healthy?

There are various ways to ensure soils remain healthy. Farmers should use more organic manure instead of synthetic fertilisers. They should also avoid monocropping and instead grow diverse crops that benefit the soil. Legumes, for example, are excellent nitrogen-fixers.

Practices such as minimal tillage help preserve soil structure and microorganisms. Integrating trees on farms provides shade, improves moisture retention and enriches the soil through leaf litter.

In addition, farmers should have their soils tested regularly, because understanding what the soil needs is the first step towards managing it sustainably.

What is the

relationship between climate change and soil health? How are they connected?

Soil and climate are deeply interconnected. Degraded soils release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, while healthy soils act as carbon sinks, storing it safely underground. Increasing soils’ organic carbon is one of the most effective natural ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions while improving productivity.

By adopting climate-smart agriculture, we embrace practices promoting soil health and enhancing resilience and mitigation against the effects of climate change.

How does the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT support farmers improve soil health?

At the Alliance, we use science and partnerships to co-create solutions with farmers, strategic partners and governments. We train farmers on soil health and sustainable soil management; this happens through initiatives such as the CGIAR (Consortium of International Agricultural Research Centers) Science Programme on Multifunctional Landscape and Biodiversity for Resilient Ecosystems in Agricultural Landscapes (B-REAL) Projects.

Last year, we collected and analysed soil samples from three sites¾at aggregated farms in Agoro East and Jimo East, Kisumu and at traditional smallholder farms in Vigulu, Vihiga. We assessed the soils’ physical, chemical and biological properties. The study, which employed advanced metagenomic techniques, provided a detailed look at the diversity and function of soil microbes. [Metagenomics is the study of the genetic material from a community of organisms, such as the bacteria in the gut or microbes in soil, directly from their natural environment.]

Physically, soils ranged from sandy loams to clay, with Vigulu exhibiting the most stable loamy structure, ideal for diverse cropping. Chemically, Vigulu’s slightly acidic soils (pH 5.4–7.0) supported better nutrient uptake, while Agoro East and Jimo East’s alkaline conditions limited nutrient availability. Organic carbon was highest in Vigulu, reflecting sustainable farming practices, while Agoro East recorded low levels, indicating long-term soil degradation.

Nutrient analysis showed nitrogen was severely deficient in Agoro East and Jimo East, largely due to years of grazing and underuse, while Vigulu had optimal nitrogen levels supporting vigorous crop growth. Phosphorus levels varied widely across sites due to fixation issues, while potassium levels remained moderate to high, although they were imbalanced with calcium and magnesium.

Micronutrient deficiencies, especially in copper and boron, contrast with elevated manganese and aluminum levels that could pose toxicity risks in acidic soils. These findings underscored the need for balanced nutrient management and organic matter enhancement to restore soil fertility.

The biological analysis revealed a rich and complex microbial ecosystem, particularly in Vigulu, where bacterial and fungal diversity was highest. Beneficial nitrogen-fixing bacteria such as pseudomonas and bradyrhizobium thrived in Jimo East and Vigulu, while Agoro East soils were dominated by decomposers like streptomyces.

Fungi including ascomycota and basidiomycota played

vital roles in organic matter decomposition and antibiotic production.

Functional insights from the metagenomic analysis highlighted how these

microbes contribute to nutrient cycling—with rhizobium fixing

nitrogen, pseudomonas solubilising (making soluble) phosphorus,

and streptomyces, penicillium and aspergillus aiding

decomposition.

These findings point to a clear pathway for enhancing soil microbial diversity as a natural means to boost crop productivity and reduce reliance on synthetic inputs. Against this background we are now training over close to 100 people on soil health as the first step towards ensuring sustainable change in terms of healthy soils.

Soil health, whose responsibility?

Soil health is a collective responsibility. Farmers need to adopt the right practices that promote soil sustainability. Governments should prioritise soil health in agricultural and environmental policies, support soil testing services, encourage sustainable land use and integrate soil education into extension programmes.

Scientists, need to conduct soil testing but also to inform,

educate, and influence attitudes towards healthy soils. We must continue

researching and sharing new knowledge and technologies that address emerging

challenges.

Public awareness is equally vital. People must understand the importance of healthy soils through media engagement and other communication platforms. Protecting the soil is everyone’s responsibility.