If you are expectant, you might be better off praying for labour to begin after dusk.

That is because, contrary to widespread assumptions, giving birth at night or during weekends appears to result in slightly better outcomes for mothers and their babies.

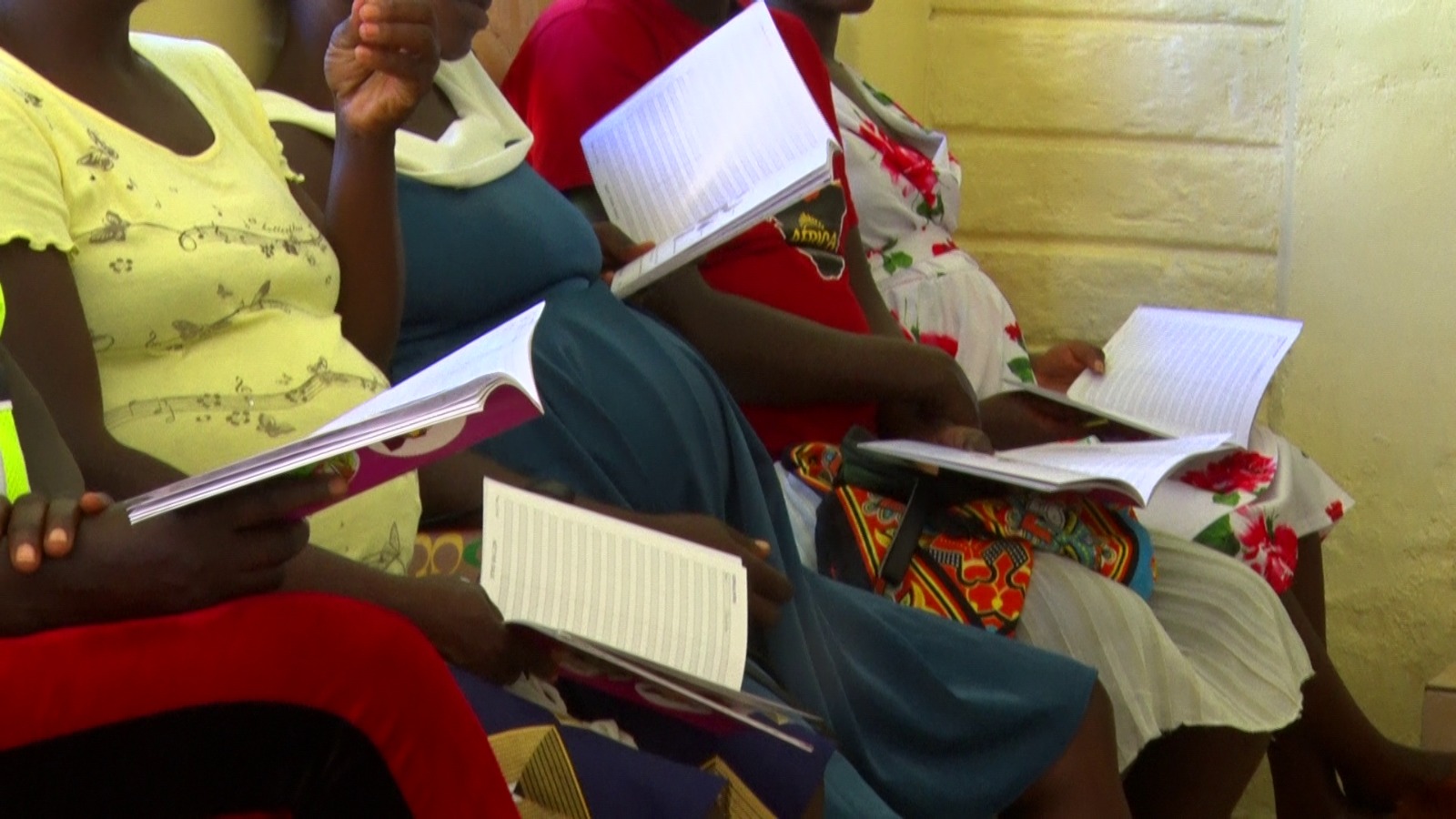

This is according to an analysis of nearly 26,000 deliveries conducted at Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (MTRH) for one year.

Researchers had hypothesised that night and weekend deliveries – times often plagued by staff shortages –would correlate with increased maternal and neonatal complications.

Instead, they found the opposite.

“We did not observe these associations, and, furthermore, saw a slight protective association between weekend deliveries and composite maternal and birth outcomes,” the authors wrote last week.

They include medics from Moi University, MTRH, and the University of Washington, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Indiana University all of the US.

Their analysis, published in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth last week, offers a cautiously optimistic insight that challenges prevailing concerns about off-hour care.

They reviewed 25,911 births from September 2020 to November 2023.

At least 62.6 per cent occurred at night or on weekends. Deliveries during these periods were associated with an eight per cent lower risk of adverse maternal outcomes and a similarly reduced risk of poor birth outcomes, including preterm birth and low birth weight. Emergency caesarean deliveries were also less frequent during these hours.

These results stand in stark contrast to global fears that reduced staffing at night leads to missed complications and delayed interventions.

At MTRH, Kenya’s second-largest referral hospital and a major training hub, night shifts may be staffed by fewer but more experienced or focused professionals.

The authors speculate that staff during these hours may be less burdened by administrative demands and more attentive to patients. It’s also possible that deliveries occurring during weekends and nights are less likely to involve medically-induced labour or non-urgent surgical interventions.

But while the timing of delivery showed modest influence, more powerful predictors of poor outcomes were evident.

The study found that maternal transfer from another facility dramatically increased the likelihood of complications and neonatal death.

Women transferred in during labour faced a 42 per cent higher risk of maternal complications, a 28 per cent increased risk of birth complications, and more than double the risk of neonatal death compared to women who delivered at MTRH from the start.

Age also mattered. Mothers under 24 had better outcomes, while those over 35 faced significantly higher risks. The presence of maternal or obstetric complications (such as preeclampsia, anaemia, or previous C-sections) was also strongly associated with adverse results.

In Kenya, for every 100,000 women who deliver in hospitals, 355 of them die from various birth-related complications. This translates to nearly 5,000 maternal deaths each year. More than 80 per cent of these deaths are attributed to poor quality of care.

The study’s lead authors urge caution in interpretation of the notion that weekend or nighttime delivery is safer.

“These findings may in part be attributed to our study site, which is a relatively well-resourced delivery centre,” they noted.

“They may not reflect those of other, lower-tier or rural facilities in Kenya.”

Their study is titled: “Associations between nighttime or weekend deliveries and adverse maternal, birth, and neonatal outcomes.”

MTRH serves as a catchment area of more than four million people and is embedded in the AMPATH network, an academic collaboration spanning Kenya, North America, and Europe.

The hospital’s resources and staffing patterns is significantly stronger than those of smaller or rural hospitals, where night and weekend coverage remains thin and often inconsistent.

The authors were also careful to point out methodological limitations. Timing of delivery was used as a proxy for staffing levels, as the study did not record the actual number or qualifications of staff present during each birth.

Moreover, the authors were unable to distinguish between spontaneous and induced labour, or to classify caesarean sections with absolute precision.

Still, the findings raise important questions about how health systems can structure maternity care to better serve mothers at all hours.

In Kenya, the neonatal death rate in 2022 stood at 21 per 1,000 live births.