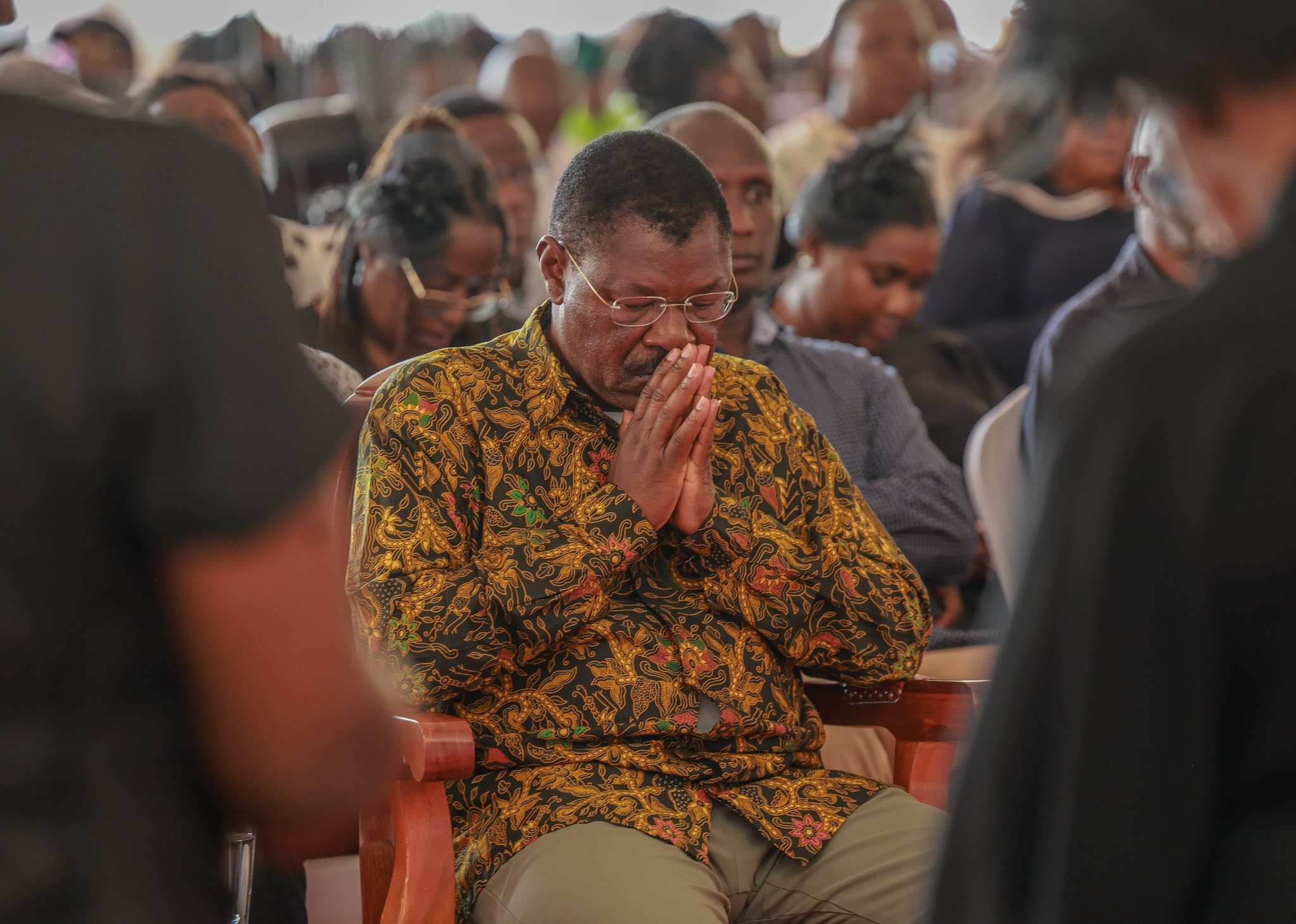

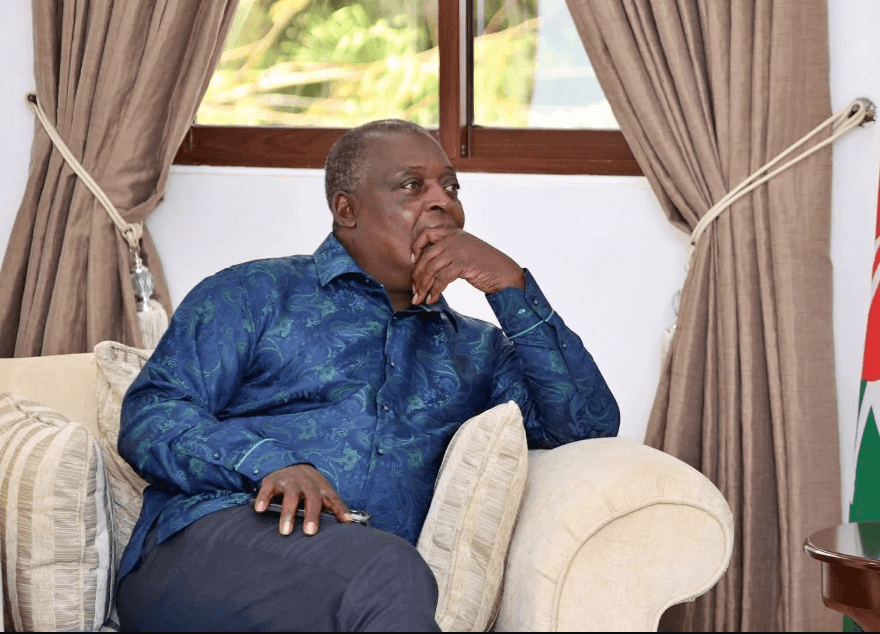

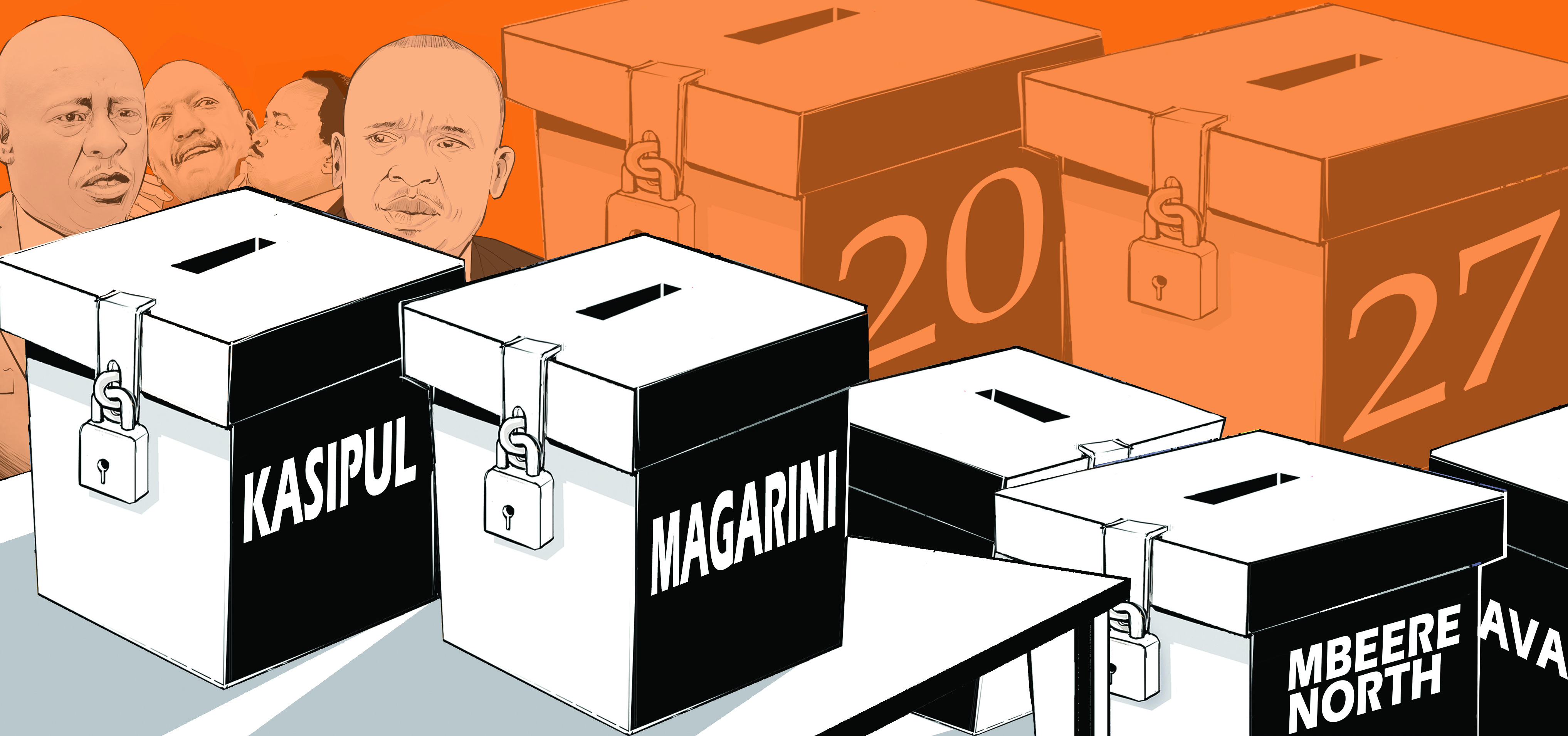

In the recently concluded by-elections, some instances of political unrest were witnessed; particularly the violent incidents witnessed in Kasipul, Mbeere North, Kabuchai and pockets of other constituencies.

These incidents have once again exposed a costly weakness in our political culture: the normalisation of electoral hostility. While such episodes may appear localised or momentary, their effects ripple far beyond the polling stations.

Economically, such disruptions act as negative

signalling shocks

that undermine investor confidence, distort market expectations and the

long-term course of Kenya development.

In the world of investment and finance, confidence is currency. It is the silent underpinning that can attract capital, propel innovation, entrepreneurship can be stimulated and maintain the macroeconomic growth at a consistent level.

Whenever violence breaks out during elections, whether big ones or even small by-elections, the message that is relayed to both local and foreign investors is clear; there exists a high risk of political instability. And in case of increase in political risk the investment recedes.

Kenya is not an isolated case. Investors compare environments, assess patterns and follow risk analytics. They are monitoring the election unrests in Kenya and then they glance at the recent history of countries where campaigns have been relatively peaceful.

They refer to nation states where political change (mid-term, national) occurs without street battles or intimidation. They see through the example of the United States where elections are very heated, though the economy does not become stagnant as the institutions absorb tension. Capital is thus out-flowed to such markets as are seen to be predictable, legal, and under effective democratic rules.

Political violence, therefore, is more than a social tragedy; it is an economic liability. It increases borrowing rates, currency instabilities, decelerates on business expansions and acts as a deterrent to long-term commitments like green field investments.

No foreign or local investor will place a significant amount of capital on a country whose election term is a habit of endangering businesses. This is also felt even by ordinary Kenyans; interrupted supply chains, price instability, loss of employment opportunities and slowed development in the region.

Political violence also undermines Kenya’s long-term competitiveness in the regional and global marketplace. Investors today compare countries not only by tax incentives or market size, but by institutional stability and governance reliability. Every incident of unrest pushes Kenya a step behind its peers, making it harder to attract sustained capital inflows.

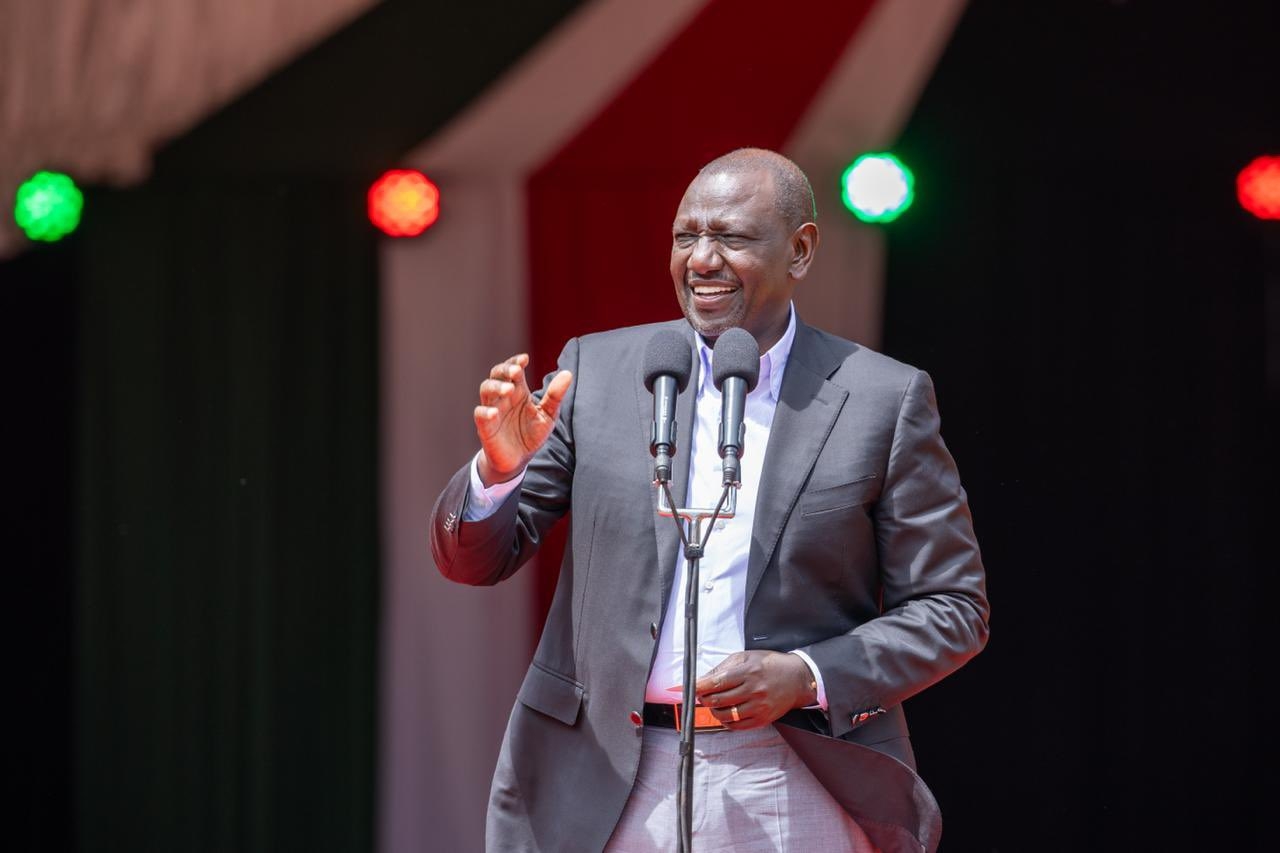

The violence witnessed during these by-elections also serves as a troubling litmus test for the 2027 general election. If tensions flare in small electoral contests, it signals deeper structural fragilities that could magnify during national polls; threatening market stability, investor confidence, and Kenya’s broader economic reforms.

There is also a deeper national question that we must confront with honesty:

If we destroy our business environment in the name of politics, how will we survive as a country?

Every burned marketplace, every disrupted business, every violent confrontation erodes the very foundation upon which Kenya’s economic aspirations are built. We cannot speak of becoming a middle-income or first-world economy while treating election-related violence as an acceptable, periodic inconvenience. Progress demands political maturity. Investment demands stability. Development demands responsibility.

It is thus a civic and moral responsibility both among the politicians, their followers, institutions and even simple citizens to protect the economy against political seasons. Leaders should reject violence; security agencies should apply the law without discrimination and citizens should reject the encouragement of violence. The competition between the political powers must not jeopardise the prosperity of the country.

If Kenya is truly committed to achieving sustained economic transformation, then controlling our political temperatures is not optional; it is existential. Is stability a luxury or an economic strategy? Peace exists not only when there is no conflict but it is the basis on which the investor confidence, national unity, and prosperity in the long term is established.

Kenya’s future depends on the choices we make at every polling station, in every political rally, and in every community. We must choose peace; not just for the integrity of our democracy, but for the survival and flourishing of our economy.

The writer is an economist and a business consultant