I first got an insight into the complex challenges facing Kenyan tourism on the occasion when I arrived early at a media briefing which was to take place at one of Nairobi’s upmarket hotels. And since the only people in the room that had been set aside for this event were me and the young lady who had been assigned by the hotel management to look after our group, she and I got chatting.

We ended up talking about career opportunities in the tourism sector, and in this context, she showed me a video she had on her phone, which a former classmate had sent her a few weeks back. And what I saw there was a remarkably long queue of young job applicants, somewhere in the Nairobi CBD, each with a large envelope in hand,

I say the queue was remarkable because whoever made that video walked around quite a bit in order to leave the viewers in no doubt that the queue went around at least two or three CBD city blocks. And it was not a single-line queue either: there were roughly three people abreast, in that queue, adding up to hundreds of applicants.

I asked her how many jobs were available for which this mass of young applicants was queuing in the hot sun. She answered, “I think around 50.”

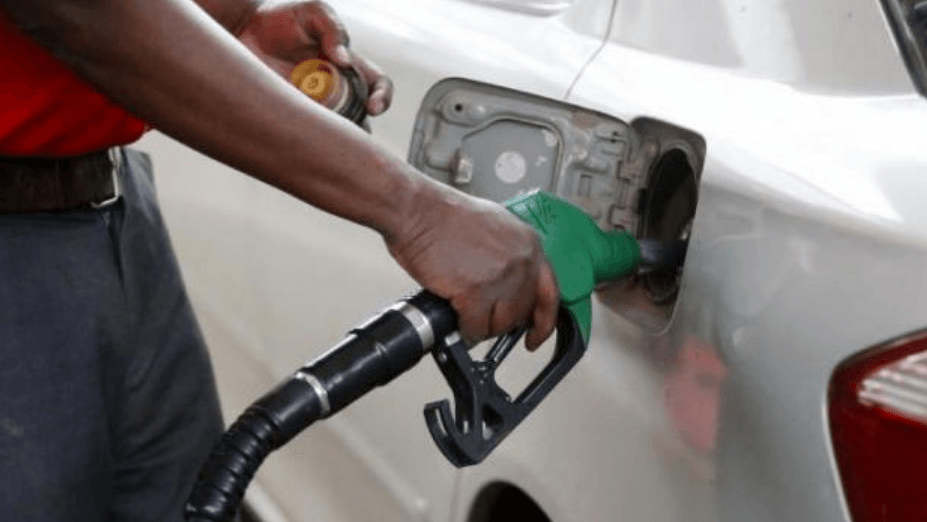

This story illustrates one of the problems that Kenyan tourism has faced over the past few years. Following the establishment of the government-owned Utalii College back in the 1970s, there has been a rapid expansion of privately owned training institutions for the tourism sector. Tourism was long considered one of the more certain investments when it came to tertiary education: after all, if the recent graduate could not find a job in a big “tourist-class” hotel, they could always go to a small restaurant catering to local clientele.

All that has since changed, and by all accounts we have a huge oversupply of trained personnel in the tourism sector.

So, you would think that any new investments in this sector would be welcome with open arms, and that the more additional tourist-class hotels there were in Kenya, the better.

Well, the controversy over the (relatively new) Ritz-Carlton Maasai Mara safari camp would suggest otherwise. There have been loud complaints from various tourism industry and Maasai community stakeholders that this supremely exclusive safari camp should never have been built at all.

Controversy over just how many such tourism facilities the Maasai Mara can sustainably support is nothing new. Nor will this be the last time when a newly built camp is alleged to be effectively blocking a key access point for the iconic annual wildebeest migration.

If I was to summarise the problem in one word, it would be a word I only first came across a few years ago, and even then, never thought I would see used to apply to Kenyan tourism.

That word is “overtourism”.

It describes a situation in which a key tourist attraction becomes so popular that, in time the local authorities have no choice but to limit the numbers of visitors permitted to enter it.

The phrase is usually associated with European cities famous for their architectural marvels or famous museums: Venice, Barcelona, Lisbon, Rome, etc.

But there can be no doubt that this is much the same phenomenon that currently troubles our own Maasai Mara Game Reserve.

If the regulatory authorities were to ignore environmental limits and licence just about any new investor who wanted to set up their camp or lodge within this world-famous game park, I have no doubt that dozens of new tourism facilities would spring up within months, in the process totally devastating the park, and ruining those wide open spaces of pristine wilderness beyond any hope of regeneration.

And yet we have all those unemployed (and well-qualified) young Kenyans looking for a job in this very sector.

And we also have several game parks (Tsavo East and Tsavo West; Meru National Park; Samburu National Park; etc) which can yet support many more tourism establishments, without any damage to the wilderness ecosystem.