Kenya is staring at a deepening water crisis as a massive $2.52 billion (Sh325.57 billion) funding shortfall threatens long-term management of the country’s already scarce water resources.

Experts are warning that if the government and private sector players do not act fast cost of inaction could drain billions from the economy and leave millions without reliable access.

A new report on water resources management estimates that the country requires nearly Sh995 billion by 2030 to secure universal access to safe water and sanitation, but is currently grappling with a Sh325.6 billion ($2.52 billion) funding gap.

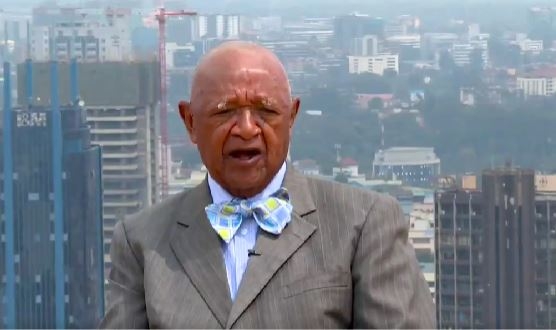

Gatsby Africa program director Abdi Wario, says that the shortfall, if not bridged, will compromise efforts to conserve catchments, expand storage infrastructure, recycle wastewater and prepare for climate shocks such as prolonged droughts and destructive floods.

According to the report, Kenya’s water availability per person has dropped to 647 cubic metres annually, far below the global benchmark of 1,000 cubic metres.

Projections suggest this will shrink further to 426 cubic metres by 2030, pushing the country into the category of “absolute water scarcity.”

Wario cautioned that without new investments in water harvesting, groundwater recharge and basin conservation, the situation could undermine Kenya’s competitiveness.

“The little water we have is not well managed. We risk over-extraction of groundwater and pollution of surface water, which will only push costs higher for households and industries,” he said.

The survey further shows that the economic toll of poor water management is already significant with Kenya losing an estimated $1.5 billion (Sh193.8 billion) annually due to inadequate access to clean and safe water for households and businesses.

Two critical basins the Athi and Tana which support key economic hubs including Nairobi, are projected to face demand-supply deficits by 2030, threatening manufacturing and job creation.

“We cannot expect the government to shoulder the burden alone. The private sector, as beneficiaries, must also contribute to financing solutions such as wastewater recycling and adoption of efficient irrigation technologies,” said KEPSA chair of the Environment and Sector Board John Wandaka

The report shows that donor funding remains the backbone of Kenya’s water sector. Between 2018 and 2024, development partners—including the World Bank, African Development Bank, and Germany—pumped over Sh258 billion in loans and grants into water-related projects.

The experts say this heavy reliance on external support has exposed structural weaknesses.

The government often struggles to provide counterpart funding required to unlock donor commitments, while bureaucratic bottlenecks and lengthy procurement processes slow down disbursement.

As a result, many projects are either delayed or underfunded, undermining the overall impact of development assistance.

To close the gap, experts are calling for a blended finance approach a mix of public funds, donor support, commercial financing, and private sector investment.

This model would spread the burden of financing while tapping into new sources of capital, particularly from industries that rely heavily on water.

“The issue is that sometimes we have finances from our development partners, but counterpart financing from the government and other key players is not readily available; with that, we cannot manage our water resources the way we should,” added Wandaka.

Equally troubling is the issue of non-revenue water, with urban utilities projected to be losing up to 43 per cent of water to leakages and theft.

The experts argue that plugging these losses could be one of the cheapest financing solutions, freeing up billions that could be reinvested into the sector.

The report now warns that the consequences of failing to act are clear. The Athi and Tana basins, which feed Nairobi and surrounding industrial hubs, are projected to face severe deficits, threatening manufacturing, jobs, and food supply.

Over-extraction of groundwater, poor wastewater recycling, and inefficient irrigation could further strain already limited resources.

“Unless we rethink financing and management, water scarcity will cripple Kenya’s competitiveness. Industries will relocate, food production will suffer, and households will pay more for less water,” warned Wario.