Walking in Michuki Memorial Park recently, along the banks of the Nairobi River, both authors found plastics and other polluting materials visible to the naked eye.

A river through the heart of the city should be a

place for leisure, sightseeing and enjoying nature. Instead, we avert our eyes,

and even hold our noses.

We are talking about more than the pleasures of walking beside a clean river, however. It is a lovely idea to live overlooking a lake, while farmers want river water for irrigation. For others their waste disposal value is important. Yet, for society more widely, the use of these areas needs to be limited.

Rivers are for many the only source of water, for washing, cooking and drinking.

Rivers are a source of water for irrigating crops. Would you like the idea of eating things watered by the Nairobi River?

Rivers eventually reach the sea. They carry the detritus of the communities through which they pass. At least a million tonnes of plastic enter the world’s oceans each year, mostly originating from land sources and washed into the sea by rivers.

The areas bordering rivers and lakes are specially regulated. They are called ‘riparian’ areas - from the Latin for banks.

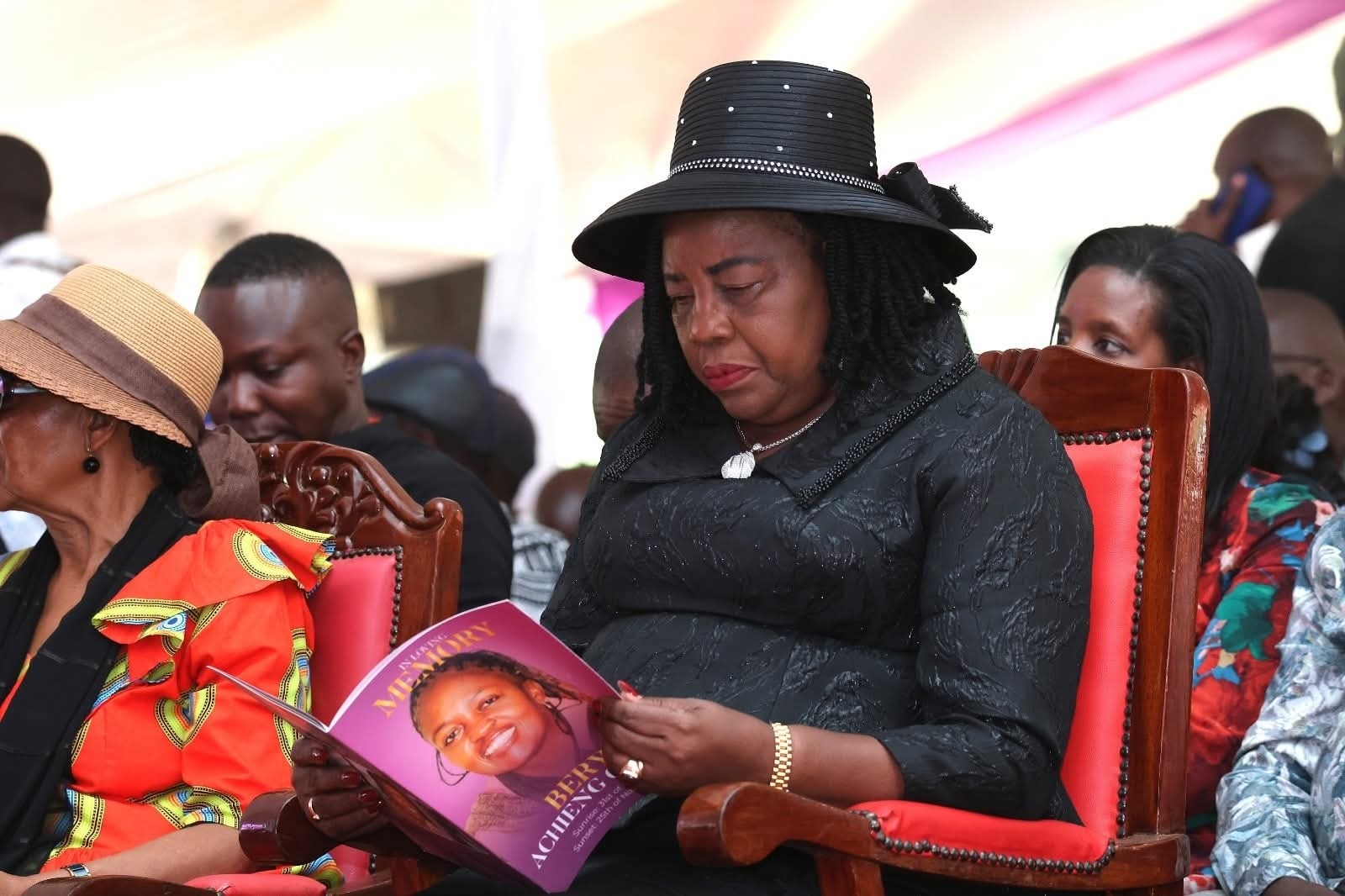

River banks of Nairobi

Riparian zones play an essential ecological, social and infrastructural role in urban environments. They serve key ecological functions include stabilising riverbanks, filtering any pollutants, and supporting stormwater absorption. Banning risky activities there further protects the water.

In Nairobi, however, riparian zones have increasingly been built

on for residential, commercial and industrial use. Pollution from inadequate

waste systems infrastructure for industry and for residential settlements has

severely degraded river ecosystems.

Decades of rapid urbanisation, weak land-use enforcement and

informal settlement growth have profoundly transformed riparian areas,

particularly along the Nairobi, Mathare and Ngong rivers.

We are experiencing riparian encroachment on a grand scale as the city grows and as the value of land rises. The approach seems to be ‘build and be damned’. This will not lead to sustainable and socially equitable outcomes and we need to think about problems now before they become too severe and too expensive to correct.

Numerous developments — formal and informal — have been erected within riparian areas despite regulations prohibiting such activity. Developers often take advantage of weak enforcement, calculatedly constructing buildings within protected areas. Informal settlements, constrained by limited affordable land, also expand into riparian corridors.

The negative consequences of this are not only to the water and its users; people have died when their homes built in such vulnerable areas were flooded.

This ecological harm is matched by social injustice. Government efforts to reclaim riparian land have often led to evictions. Residents of informal settlements — who frequently lack formal tenure — face disproportionate displacement.

There have been accusations of selective enforcement, extortion and inadequate compensation. Indeed, there may be no right to compensation, which can be due to those who in good faith believe they are entitled to land (Article 40(4)), but not to those who know they are squatting.

Riparian law in Nairobi reflects intertwined challenges of urban growth, environmental degradation and social inequality.

‘Riparian’ needs to be defined by law. Historically, unclear legal definitions of riparian width, overlapping mandates across agencies and corruption in land administration have made riparian land vulnerable to encroachment. These weaknesses have contributed directly to increased flood risk and to river pollution.

Multiple laws govern riparian zones, but their definitions and enforcement mechanisms often conflict. Key agencies — such as the National Environment Management Authority, Ministry of Lands, Nairobi county and the Nairobi Water, and the National Water Authority — lack clear coordination. This contributes to irregular approvals, ambiguous zoning, and ineffective monitoring.

There is a lot of confusion about riparian land and who is responsible for it. The constitution says that rivers as such are public land (Article 62(1)(i)) and so are “water catchment areas” (Article 62(1)(g)) and held by the national (not county) government.

The latter means an area in which water (including rainwater) flows into a particular river or other water body (much more than riparian). Realistically. This cannot all be public land. It must be classified, and gazetted, under some other law.

The Land Act says the National Land Commission may not allocate to anyone public land that is riparian or a catchment area. The new (2025) Water Resources Regulations are clear that riparian land can be owned, but is subject to restrictions by the Water Resources Authority.

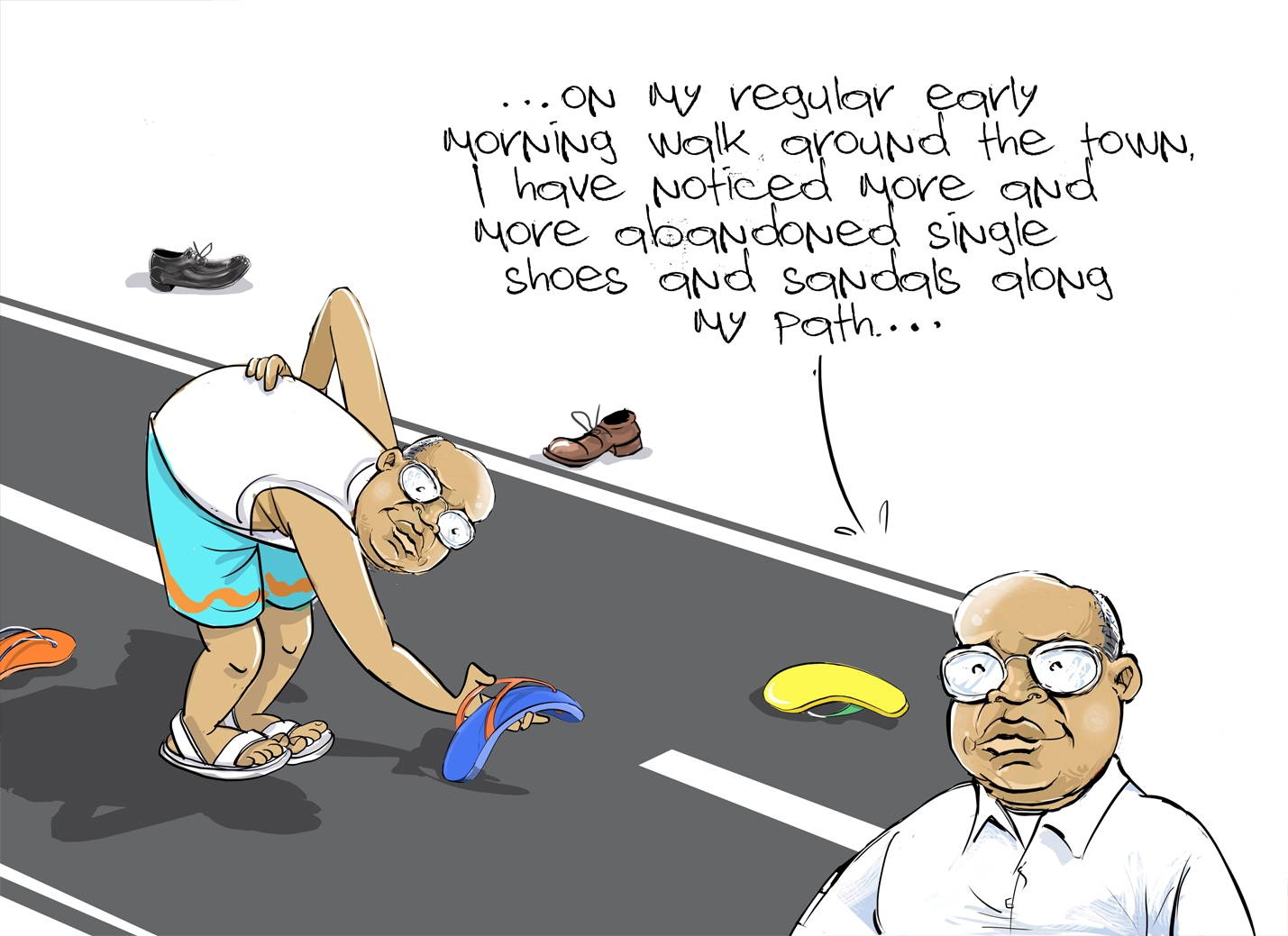

Enforcement is sporadic. Many may remember former Governor Mike Sonko’s new broom effort to remove building developments too close to rivers ¾ presumably the result of developers ignoring the law, or obtaining permission by bribery.

And now, on some sites, similar or greater development has replaced that which was demolished. (You might be interested, and depressed, to watch the Chamwada Report from KTN in 2018 on the Water Resources Authority website at https://wra.go.ke/wra-defines-the-riparian/.)

This year, Nairobi county designated the Nairobi River corridor as a Special Planning Area. This framework establishes a 60-metre buffer zone (30 metres riparian reserve and 30 metres development control zone) and initiates a two-year planning process to regenerate the area.

A large-scale initiative was launched, involving river widening, construction of a 60-km trunk sewer line, creation of green infrastructure and development of affordable housing near affected zones. The programme aims to address both environmental and social objectives. Authorities have pledged that evictions will follow lawful procedures and incorporate fair compensation or relocation.

Some stakeholders argue that the 60-metre buffer overextends legal definitions of riparian zones under environmental regulations. The debate reflects broader conflicts around land rights, property values and displacement risks.

The Constitution

Law that is sometimes enforced and sometimes not is not law. And off-and-on-and-off-again law enforcement is a clear violation of the rule of law ¾ a national value that is supposed to bind everyone, making, applying or enforcing law.

Though we cannot look to the Constitution for specific solutions on riparian law, various concepts in the Constitution do offer an underlying approach. One aspect is the national value (Article 10) of sustainable development.

This concept embraces the idea of fairness to future generations,

but also as between those living now. Those who have access to riparian areas

and use them in a way that is unfair to others (by polluting the water, taking

excess quantities of water, or building in a way that prevents proper water

protection) are not complying with this constitutional value.

And Article 60 lays down principles of land use including sustainable management and sound conservation. These provisions reflect an important reality and a philosophy: you may own land, but it is not yours to use just as you please. In a sense, you hold land in trust for the nation, indeed, one might say, the world.

We - the people and governments of Kenya - know what needs to be

done. The big puzzle is how to get it done.

Manji is professor of land law and development at Cardiff School of Law and Politics. Jill is a retired law teacher and member of the Katiba Institute Board