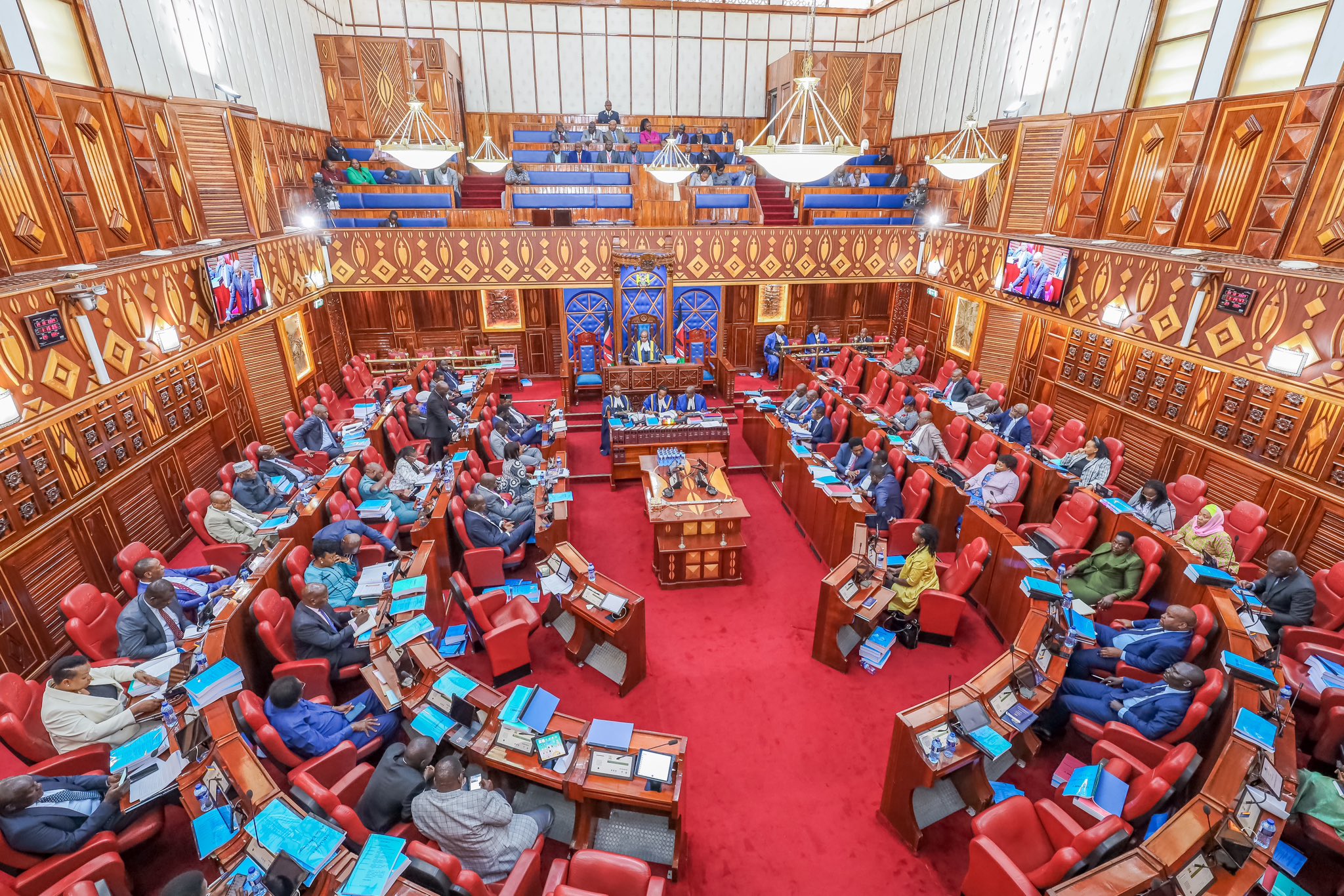

Senate in session /FILE

Senate in session /FILE

Towards a new Constitution

When “devolution” was decided on (Constitution of Kenya Review Act of 1997), it seemed natural to have a second house of Parliament. Most systems with multi-level governments do and all the draft constitutions included it (except the 2005 draft rejected in a referendum, because it also rejected devolution). But they changed quite a lot.

There are two closely connected aspects: the members and their role. I am focusing here on their role in connection with devolution rather than in representing certain groups.

Under the various constitution drafts, Senate would either have represented their lower units’ governments (the ones we now call counties) or would have been elected by the voters of the district/county.

The Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) 2002 draft included a “National Council” made up of the chairpersons of the 70 district councils (the main level of devolution). The National Constitutional Conference (Bomas) draft, 2004, called that body the Senate. Its members were to be elected by the district council but represent their region (of which there were to be 14).

In the Committee of Experts (CoE) first draft (2009) each county assembly would have elected a Senate member. Their revised draft abandoned the connection with county government - senators were to be elected by their county voters. This is the position under the constitution now.

Which idea is better?

The South African National Council of Provinces (NCOP) members represent provinces. Each province has a delegation to the NCOP, including the provincial premier, some from the provincial legislature and others appointed by that legislature (reflecting the parties in that legislature).

The NCOP clearly represents the provinces and their parties and supports the system of devolved government. It looks at all national legislation but its approval is only required for laws affecting provinces. It is also involved in any constitutional amendment.

I have wondered whether this might have been a better model for Kenya, thinking that we might have avoided the current situation where Senators envy governors and are resented by the National Assembly.

However, it is not clear how well the system works in South Africa, for various reasons. It would have been even more problematic here because we do not have that intermediate level of government – provinces in South Africa and, under our Bomas draft, regions.

Secondly South Africa is basically a parliamentary system and the premier and provincial executive are members of the provincial assembly.

Just imagine that system here: all 47 governors and a few others from the county assembly - may be at loggerheads with each other. Or even the CoE proposal of a member from each county, elected by the county assembly. What respect would they have?

The CoE abandoned their scheme because people suggested that indirectly elected senators were unlikely to be of “the right calibre” and “without popular support would carry less weight than members of the proposed National Assembly”.

Role of the Senate

Under the CKRC 2002 draft, the Senate would have considered all bills but money bills could not begin in the Senate and it would have had very little impact on them.

Now the Senate only deals with bills that “concern counties”. Money bills (about taxation, dealing with public money or public loans) do not go to the Senate at all, except for those that every year divide revenue raised nationally between the national government and the counties and then amongst the counties.

A lot of private members’ bills are introduced in Senate that seem to trespass on the counties’ power.

Under that CKRC draft, Senate would have approved appointments to all commissions, the Attorney General, Director of Public Prosecutions, Public Defender (a post regrettably lost along the way), the Police Commissioner (IGP equivalent), Director of Correctional Services, Judges and the Chief Kadhi.

Under the Constitution now, the National Assembly (NA) approves almost all appointments. Of the list in the previous paragraph, only the IGP is approved by “Parliament”.

But the Senate has important powers. Every five years it decides the basis on which money is divided between national and county levels. The NA can overturn it but only by a two-thirds vote.

This process is time consuming, especially for the Senate committee. They must consider recommendations from the Commission on Revenue Allocation (CRA), consult the governors, the Cabinet Secretary for Finance and the Council of Governors. They must also invite public input, receiving substantial submissions from expert bodies, as well as take, into account relevant constitutional principles. They deal with pressure from counties wanting more for themselves. So, in this year’s exercise, in the end poverty counted for less and the share common to all counties was greater, than the CRA recommended.

The Senate also acts as a sort of court - when the President or Deputy President or a Governor is impeached. I suggest that the County Governments Act giving the this task involving governors gives too tight a time frame. The committee that may deal first with the matter has just 10 days to report to the whole house. That is just not enough for a complex case that could involve a lot of evidence. On average, the Senate has dealt with just over one impeachment per year.

The big mistake

When the CoE second draft constitution went to the parliamentary select committee, it did a couple of odd things. It described the Senate as the “Lower House” of Parliament. This, said the CoE, would be “a constitutional absurdity”.

The other thing was to add to the Senate’s powers “oversight over funds devolved to the county governments”. The CoE does not seem to mention that and did not remove it. The most obvious problem is this: how could oversight be limited to funds devolved, excluding locally raised funds that might be spent on the same projects?

Oversight of the county and how it spends its money is mainly the job of the county assembly (and the Auditor General and Controller of Budget) and should not be the Senate’s task.

The CoE say in their Final Report “…care had to be taken not to open wide the opportunities for interference in the affairs of the counties. … an additional provision was made requiring the national government to ensure that county governments were given adequate support and resources and a power of intervention that would be used only to maintain the integrity of the system of devolution and the provision of essential services.”

This refers to Article 190 that requires a procedure for the national government to step in to help counties that get into difficulties - and for the Senate to be able to end it. And, under Article 192, the national government may suspend a county government - leading to an election eventually – but the Senate can also end the suspension.

Another problem: Senate could not really act like an impartial court in a Governor’s impeachment case if the Senate had been involved in investigating the Governor’s management of the very same county government.

Conclusion

There may be reason for the Senate to be able to consider all the legislation proposed in the national Parliament – though I think this needs careful consideration. Would it delay enactment of legislation? Would it improve legislation? It would presumably stop the disagreements between the two Speakers over whether a Bill “concerns counties”, and the expensive court cases that have followed.

But it ought to lose the power of “oversight over funds devolved to the county governments”. And the Senate Oversight Fund -the Senate’s equivalent of the Constituency Development Fund, or perk for MPs.