By the time I closed the last page, I realised Sulwe was not just a children’s book. It was a gentle lantern in the dark, a song of belonging, and perhaps even a mirror for countless dark-skinned girls who have waited too long to see themselves celebrated.

The name Sulwe means ‘star’ in Dholuo, the language of Nyong’o’s heritage. And the book lives up to that title beautifully.

At its heart, Sulwe tells the story of a little girl with skin ‘the colour of midnight’ who feels out of place. She looks around her world and notices how beauty is praised in lighter shades, how nicknames sting and how impossible it seems to belong when you feel too different.

Nyong’o does not shy away from the truth: colourism is real, and it leaves scars. Yet the story is told with such gentleness and honesty that even the youngest reader can grasp its emotional weight without being overwhelmed.

What makes the book extraordinary is how it manages to be both deeply personal and widely relatable. She has crafted a tale that is deeply relatable to dark-skinned girls anywhere in Africa, from Nairobi to Lagos, from Kampala to Johannesburg.

This is because she taps into something universal: the longing to be affirmed, the ache of exclusion, and the transformative power of seeing your own worth. Whether the reader is a girl teased for being ‘too dark’ in a Nairobi schoolyard, or a child growing up in Accra, where fairness creams fill shop shelves, Sulwe’s journey resonates. The cultural specifics may shift, but the emotional truth is shared across borders.

Yet the relatability does not stop at geography. The story’s rhythm and imagery create a bridge for readers everywhere, whether they have lived through colourism or not. Nyong’o is not lecturing; she is storytelling, weaving myth, tenderness and honesty into something children can hold onto without feeling weighed down.

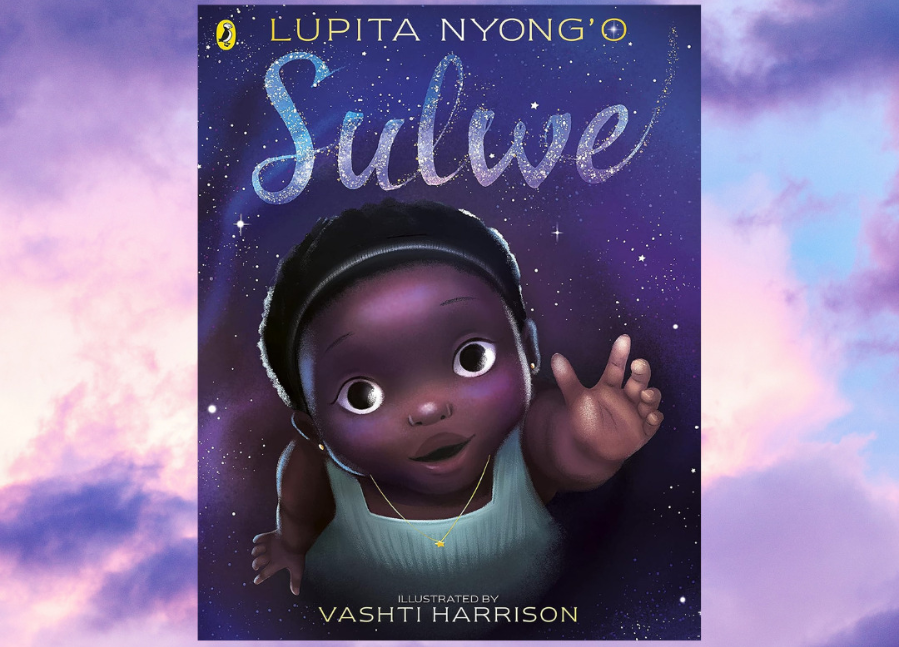

The illustrations by Vashti Harrison add another layer of magic. The pages glow with deep blues, soft violets and radiant golds, turning the story into a visual lullaby that lingers long after reading.

As I read, I found myself slipping between two perspectives: The adult who knows too well the weight of inherited biases, and the child inside me who remembers the first time someone hinted that my skin was “too much”.

I thought of the little girls I know — nieces, cousins, friends’ daughters — who might pick up this book and feel something shift inside them. It is not just a story; it is an invitation to unlearn shame, to see beauty where the world once insisted there was none.

And perhaps this is Nyong’o’s quiet triumph: She has given us a book that does the double work of healing and prevention. For children who already feel the bruise of exclusion, Sulwe offers comfort and validation. For those who have not yet encountered colourism, it plants seeds of empathy, making it harder for them to become perpetrators of those same wounds. It speaks to parents, too, many of whom may have unconsciously passed on biases they never examined.

At just over 40 pages, Sulwe is a short book. But do not mistake brevity for simplicity. It is tender enough to soothe a preschooler during bedtime, yet profound enough to spark conversations with teenagers, or even adults who still wrestle with the shadows of their younger selves.

Ultimately, Sulwe is more than a children’s book. It is a love letter to every dark-skinned girl who has ever wondered if she belonged. It is a reminder that stories, when told with honesty and imagination, can do more than entertain. They can repair. They can illuminate. They can guide us back to ourselves.