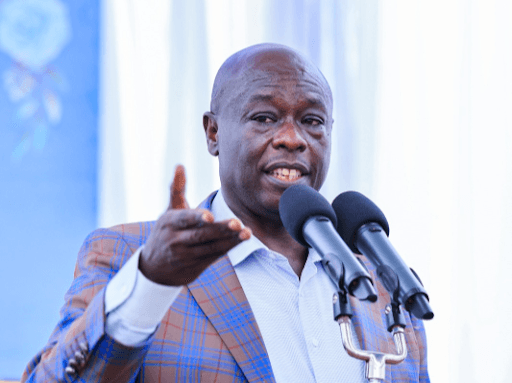

He aspires to unseat President William Ruto in the 2027 General Election in an unconventional way.

Rather than playing up ethnic affiliations or charming voters with an expensive campaign, the popular social activist hopes to secure the support of Gen Z and Millennials, who spearheaded nationwide protests last year, in a run against corruption and poor governance.

Mwangi is building his presidential campaign around empathy, honesty and the ability to "orchestrate" talent. The self-styled "orchestra leader" says his role will be to ensure the musicians produce harmony.

“I'm seeing myself as an orchestra bandleader and in an orchestra,” he told bird in a recent interview.

“The orchestra lead does not play an instrument. The band plays the instruments, and they make beautiful music. So that's what we're going to do between now and next year.”

For Mwangi, the “musicians” are everyday Kenyans, in the country and in the diaspora. He believes that human capital is one of the biggest resources Kenya has.

“We have Kenyans everywhere in the world. We are the best in almost everything," he said.

“The only problem is we export our best resource to work outside our country. And I want to bring those people to work in our country. The problems that ail our country are fixable. It's corruption, ignorance, poverty and disease, and we have the money to do that.”

Mwangi’s spirit of championing the rights of others was formed way back in his school days. Born into poverty, he was once expelled from an approved school after exposing teachers who had exploited students as servants and, in some cases, as victims of molestation.

He recalled his mother's words: “If you were silent about what you saw about the injustice, maybe you wouldn't have been expelled."

He evolved into what he describes as a "silent observer". This practice propelled him into photojournalism, a profession that gave him room to continue to observe.

As a young photographer, he documented the disturbing incidents that unfolded after Kenya’s 2007-08 election. His work earned him international recognition, but also scarred him.

“I was just a bystander again. I was someone who was photographing violence every single day. For the next couple of months, I was a very depressed person," he said, adding that he suffered from PTSD and anger.

FROM JOURNALISM TO ACTIVISM

His childhood experience and early adult life pushed him to abandon journalism in 2008 and step onto the streets as an activist. Mwangi started organising protests and public demonstrations in 2009, sometimes standing alone, holding up placards that artistically illustrated his stance against corruption and land grabbing.

He was hit with police batons, jail time and uncountable lawsuits that secured him a reputation as one of the few Kenyans willing to confront the political class head-on.

Like his activist ethos, challenging the monopoly of the political elite and placing ordinary citizens at the centre of decision-making, he has promised voters a participatory process in his manifesto making.

He said he is preparing a nationwide meet-the-people tours, dubbed, “Bonga na Bonnie (Talk to Bonnie)."

"The Kenyans who are suffering today know that they are suffering, and they know what could actually alleviate the suffering,” he said.

“So I want to go and hear them out. The plan and the master plan to fix this country will come from the Kenyan people, and that's why we have participatory democracy.”

Other places in Africa are witnessing the entry of outsiders into the political landscape, usually activists, reformists and youthful aspirants. They are shaking things up and amplifying marginalised voices.

In Uganda, musician-turned-politician Bobi Wine electrified a generation by framing politics as a battle between the old and the young, even though state machinery ultimately blunted his presidential challenge.

In Senegal, 44-year-old Bassirou Diomaye Faye, propelled by youth frustration with growing government unaccountability and the country’s ongoing allegiance to former colonial power France, defied entrenched structures to win the presidency in 2024, becoming Africa’s youngest elected head of state. His victory has become a reference point for movements across the continent searching for change agents beyond the traditional political elite.

If Mwangi breaks Kenya’s presidential ceiling, he will be the first in Kenya and will be among the few who have toppled incumbents.

In the recent past, a number of reformists have tried to attain the presidency but did not manage to attract significant votes.

In 2013, Kenya’s former Assistant Minister Peter Kenneth, running on a modernising, technocratic platform, was touted as a “third force” but garnered only 72,786 (0.6% of the total presidential votes). Veteran reformist Martha Karua, long respected for her principled politics, fared even worse at 43,881 (0.4%).

In both 2013 and 2017, Abduba Dida, a teacher-turned-activist, captured headlines with fiery rhetoric but translated that into slightly above 50,000 votes (0.4 per cent and 0.3 per cent of the votes) respectively.