“They are gentle but at the same time commanding,” he said on a call. “Every time you watch them, you notice something new: their grace, their height, the way they interact. To me, giraffes have always been different from any other animal.”

For Mulama, the new scientific classification is more than just a technical change.

“This is a unique reclassification because for the longest time, a giraffe has just been a giraffe,” he said.

“Not many people pay attention to them the way they do to elephants or lions. But this shows how much more there is to learn.”

Now, science has caught up with what field researchers and local communities have long suspected.

After more than a decade of DNA sampling, morphological studies and tracking giraffe movements across Africa, experts have reached a groundbreaking conclusion: giraffes are not one species but four.

On August 21, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) formally recognised Northern, Reticulated, Masai and Southern giraffes as distinct species.

The announcement was made by the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Giraffe and Okapi Specialist Group in Windhoek, Namibia.

The group’s co-chair Michael Brown welcomed the development.

“This taxonomic revision reflects the best available science and provides a globally standardised framework to inform conservation,” he said.

The decision overturned decades of classification that treated giraffes as a single species with nine subspecies.

Experts describe it as “the most significant shift in giraffe taxonomy” in more than a century, one that will reshape protection strategies for the world’s tallest land mammal.

“Recognising these four species is vital for accurate Red List assessments, targeted action and coordinated management across borders,” Brown said.

Namibia has provided one of the clearest success stories.

According to Explorers Against Extinction, the country is home to about 15,000 Angolan giraffes and a smaller population of South African giraffes.

In the remote Kunene region, giraffe numbers have risen fivefold since the early 2000s, supported by communal conservancies and long-term monitoring.

In northwest Namibia’s arid landscape, from the Kunene River south to the Hoanib, conservation has raised the desert-dwelling Angolan giraffe population from about 450 individuals in 2022 to 472 by mid-2024, according to the GCF.

Much of this recovery is rooted in Namibia’s communal conservancy model, introduced in 1996.

The framework grants local communities management rights over natural resources and wildlife.

Today, 86 communal conservancies cover more than a fifth of the country, creating vast landscapes managed for eco-tourism, habitat protection and conservation.

The model generates more than $5.5 million annually for local communities, revenues reinvested into anti-poaching, schools, health services and wildlife protection.

The Masai giraffe (Giraffa tippelskirchi) is also holding steady, with about 43,900 spread across Kenya and Tanzania.

Translocation projects beyond its core range, including in Rwanda and Zambia, have restored small populations, highlighting the role of cross-border collaboration in conservation.

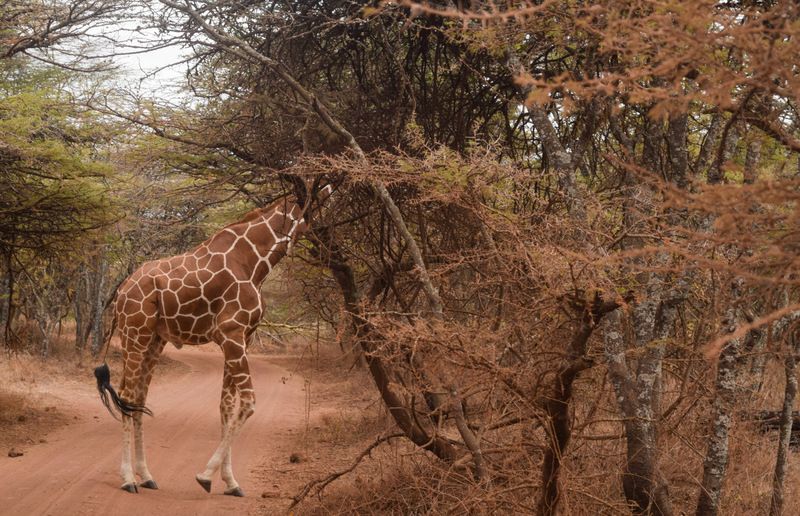

The Reticulated giraffe (Giraffa reticulata) is also a case of recovery.

Once facing sharp declines, it now numbers around 20,900.

Much of this rebound is tied to community conservancies in northern Kenya, where local stewardship and eco-tourism revenues create strong incentives for protection. Conservationists describe it as one of Africa’s more visible success stories.

The Northern giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) remains the most threatened, with only about 7,000 left. Yet even here, community action has driven progress.

In Niger, the West African giraffe has climbed from just 49 individuals in the 1990s to nearly 660 today, according to the GCF.

The recovery is anchored in community patrols and the establishment of a ‘Giraffe Zone’ east of Niamey, where local people share farmland with giraffes and benefit from eco-tourism.

To reduce the risks of having all the giraffes in one place, conservationists launched Operation Sahel Giraffe in 2018, moving eight giraffes more than 800km to the Gadabedji Biosphere Reserve.

A second relocation in 2022 transferred four more females, establishing a new wild population.

Local engagement remains central in Africa’s giraffe conservation story.

Community guides working under the Association for the Valorisation of Ecotourism in Niger lead giraffe tourism and monitoring, while initiatives like “One Student, One Acacia” encourage schoolchildren to plant trees to restore giraffe habitat.