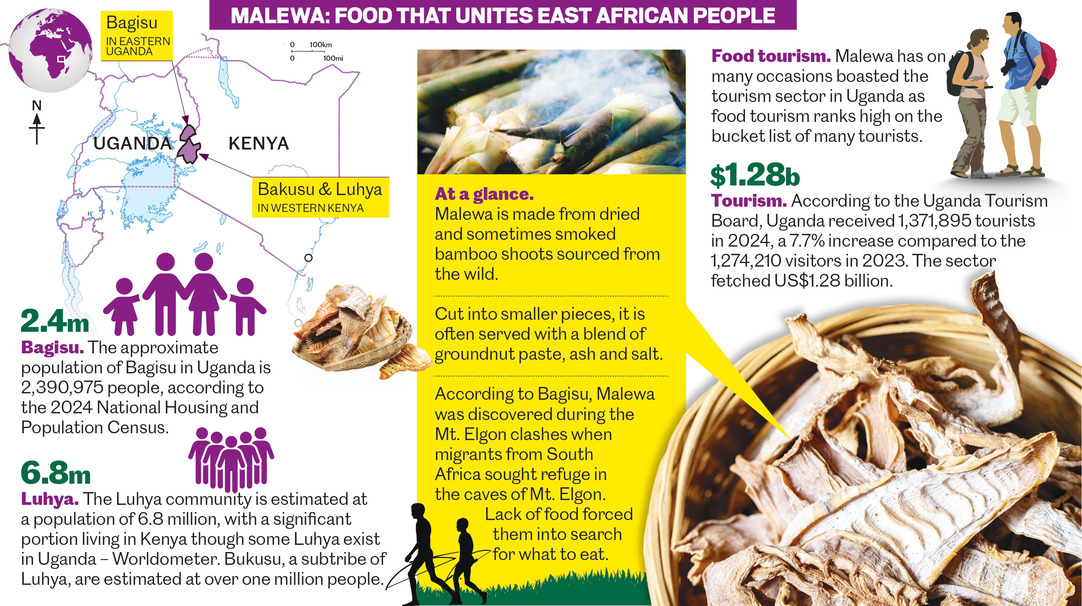

Its journey could be seen as one that mirrors the aspirations of the East African Community and tells a compelling story of free movement, food diplomacy and women’s economic empowerment.

Today, malewa graces tables in Nairobi, Mwanza, Kigali, Juba and Dar es Salaam, not only as a nostalgic dish but also as a symbol of East African identity. Its migration tells a story of intra-African mobility, one in which indigenous food travels far thanks to the efforts of women who harvest, prepare, trade and export it.

Since the EAC’s Common Market Protocol in 2010, the region has aimed to create a single economic space promoting the free movement of goods, services, capital and people.

For small-scale producers and traders, especially women, this has opened new doors. Malewa is one of the many traditional products that have benefited from this integration.

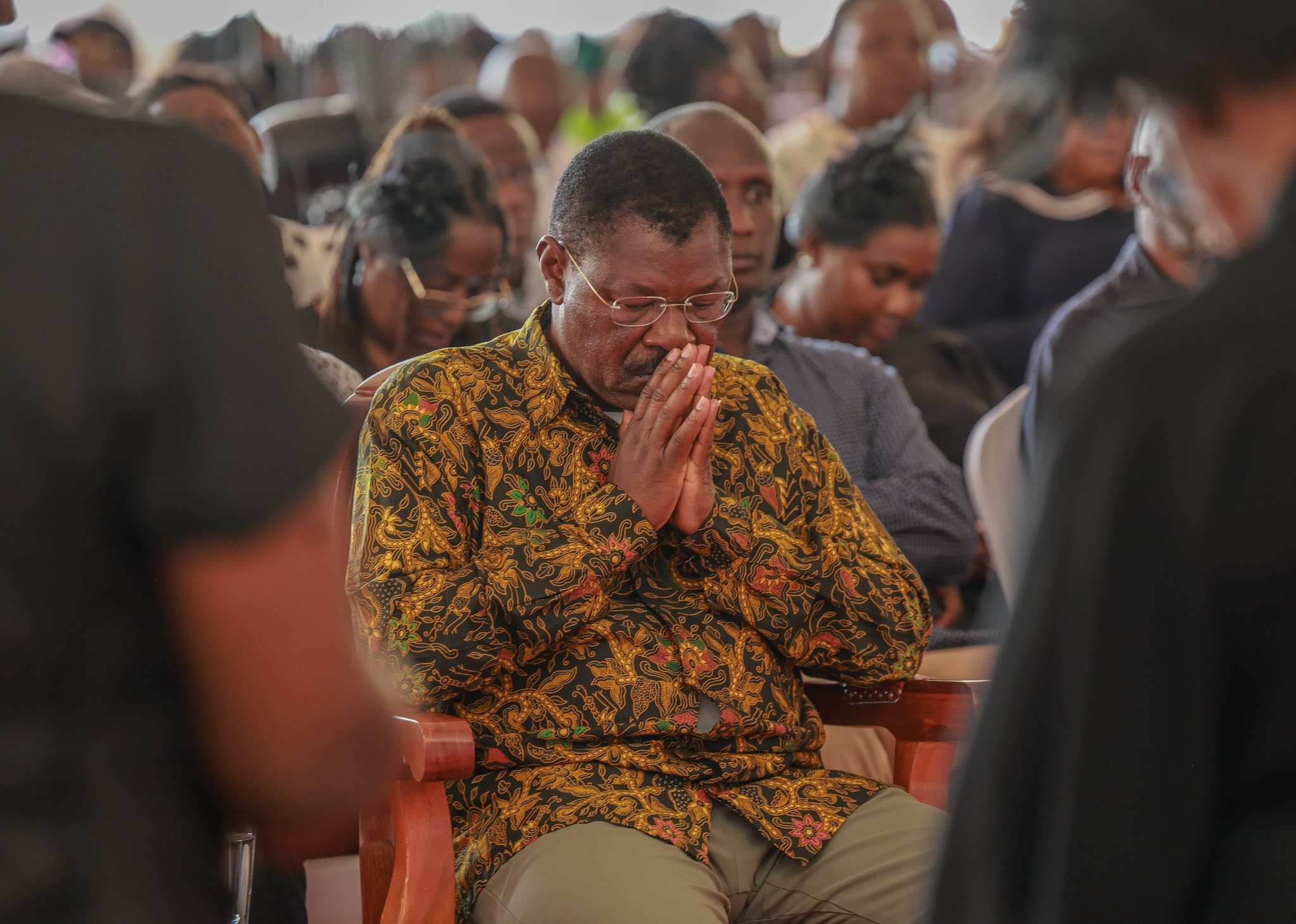

“The free movement of agricultural goods like malewa has fostered cultural unity and economic opportunity,” Uganda’s Foreign Affairs Minister John Mulimba said.

He added that regional trade is helping create cross-border networks of producers, traders and consumers who keep local traditions alive while expanding their market reach.

The East African Customs Union (2005), the Common Market (2010) and the Monetary Union Protocol (2013) have significantly reduced trade tariffs, visa requirements and transaction costs.

These policy instruments have facilitated smoother trade flows and given traditional products like Malewa a new lease of life. Informal cross-border traders, most of whom are women, are now increasingly recognised as key agents in regional economic integration.

“Many strides have been made since the integration process started,” said the Uganda Revenue Authority officer attached to Busia border customs, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“Achievements include the customs union established in 2005, common market in 2010 and the signing of the monetary union protocol in 2013.

“The cooperation has brought forth advantages like the reduction of transaction costs of local products like malewa and creation of larger markets.

“It has heightened the stimulation of investing and industrialisation, and establishment of social development that has led to addressing peace and political stability in the region.”

WOMEN DRIVE MIGRATION

At the centre of malewa’s success are women like Irene Wabule Walimbawa, who oversees the sorting and packing of malewa destined for export.

Women are deeply involved in every stage of the value chain, from harvesting bamboo shoots on steep slopes, to processing, smoking, drying and selling the final product in urban markets.

In Mbale, Jinja and Sironko, entire communities have organised informal women’s collectives that coordinate harvesting and drying schedules to meet the growing demand.

Yet, this work is not without risks.

“During the rainy season, loose soils on the mountain can be deadly,” Sylvia Namono of Sironko, a district in eastern Uganda, said.

Despite the dangers, she keeps harvesting and preparing malewa, which she sells at local and regional markets. “It is how I feed my family,” she said.

The bamboo must be harvested at a specific age and cured quickly to prevent mould, requiring both expertise and physical resilience.

Many of these women have found ways to turn traditional food knowledge into economic agency. In Mbale, where malewa is a culinary staple, women-led cooperatives are packaging it for sale in supermarkets and restaurants across Uganda and Kenya.

Their branding includes biodegradable packaging, recipe inserts and contact information for repeat buyers. Some women have begun training others in food safety and quality assurance, building a new generation of agro-entrepreneurs rooted in indigenous knowledge.

Traditionally served during imbalu (Bagisu circumcision rituals) and weddings, malewa has long been a symbol of unity and transition. “It was believed to make boys brave,” Abubakr Dawa, a 75-year-old elder, says.

Now, its meaning has evolved. With its distinct flavour, evocative of forest mushrooms, and compatibility with staples such as millet and sweet potatoes, malewa has become a regional comfort food.

The unity among the Bagisu in Uganda, the Bakusu and Luhya people has managed to popularise the consumption and sale of malewa in Kenya’s urban centres, including Nairobi, Bungoma, Kakamega, Nakuru and even Mombasa.

“I first tasted malewa at a wedding in Mbale,” says Monica Wangari from Kenya. “Now I always ask friends to bring some. It reminds me of our own forgotten traditional dishes.”

This resurgence of culinary heritage is also shaping regional identity. “Malewa has become more than food,” Steven Masiga said, spokesperson for the Inzu ya Bamasaba cultural institution, set on the slopes of Mount Elgon.

“It connects people through a shared cultural memory and taste.”

Disclaimer: This content is produced for African Women in Media as part of the MOVE Africa project, commissioned by the African Union Commission and supported by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the GIZ or the African Union.