For more than six decades, Kenya's politics have been shaped by an underlying framework of ethnic hegemony.

At the heart of this model has been the Mount Kenya region, especially the Kikuyu political elite, who have historically sought to structure national leadership around dominance, control of state resources, and the transactional logic of "coalition-building."

This hegemonic framework has been sustained by the covertly communicated narrative of Kikuyu political superiority, which at its core advances the position that leadership of the state is a right to be defended and consolidated rather than shared and that other communities are not equal partners in governance but subjugated actors who can only be "paid" or made to concede through deals and compromises if they wish to access power.

This Kikuyu transactional model of power has historically functioned as a gatekeeping system, where access to national leadership and resources is mediated through bargains that require submission to the hegemonic centre.

Coalition agreements like the Rainbow Alliance of 2002, shows of deference, and the demand for unquestioned loyalty to access resources have been the actual currency of this system.

In fact, under this model, political partnership has never been about equality, but about structured subordination, where other communities are required to submit in order to secure a place within the national order.

Right from the uneasy alliance between Jomo Kenyatta and Jaramogi at independence to Jomo and Moi’s unequal partnership, to Moi's balancing act with Kibaki as his vice-president all through to the Kibaki–Raila coalition, and later the Uhuru–Ruto pact; the pattern has been consistent; real and symbolic deference to the hegemonic order is the price of entry.

For the Gen.Z who might not be aware, the bruising battles within the 2008 Grand Coalition were less about governance and more about the mountain elite's visceral rejection of Raila Odinga's refusal to genuflect before this order, go back in history and you will learn that every attempt was made to humiliate him, a stark reminder of the unwritten rule that politics in Kenya, under this model, is a marketplace where the price of participation is submission.

It is this tradition that former Deputy President Rigathi Gachagua invoked after President William Ruto's 2022 victory when he openly insisted that Mount Kenya should take the lion's share in the distribution of government positions and resources.

Camouflaged in his rhetoric of "our fair share" was the coded demand that all business, state appointments, and resource allocation flow disproportionately to the mountain as proof of submission by President Ruto.

He put great effort to reassert that marketplace model where the mountain sat as the auctioneer, and all the other communities scrambled to purchase relevance at the price of deference.

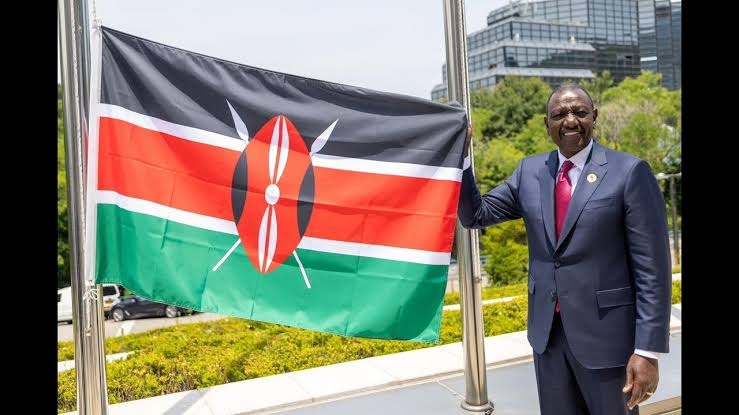

Yet, just as Raila Odinga before him famously refused to prostrate before the Mount Kenya hegemony during the Grand Coalition years, earning humiliation and relentless pushback, President Ruto charted a similar path of resistance; he refused to be tethered to Gachagua's transactional diktats and instead appealed directly to other regions through embracing the model of relational politics and thereby effectively disrupting the expected script.

The resultant acrimony between himself and the mountain elite was not an accident of personality, but the inevitable clash between two irreconcilable visions: one based on furthering a hegemonic transaction, and the other on a broader, more inclusive national project.

Notably, despite the apparent differences between former President Uhuru Kenyatta and Rigathi Gachagua, recent events have revealed the durability of this hegemonic order. Uhuru's sharp attacks on President Ruto during the Jubilee National Delegates Conference mirrored Gachagua's combative stance, symbolising a rare unification of purpose: the preservation of Mount Kenya's transactional hegemony.

What bound them was not any personal affinity but the shared instinct to defend a system where the mountain must remain the arbiter of Kenya's political marketplace.

Give it to the Mountain, this transactional model has been effective in the past, but it has also fostered feelings of exclusion, resentment, and rivalry, particularly among communities that rejected the notion of subordination to Mount Kenya given their cultural values, that would not allow them to accept a framework that reduced them to lesser partners in their own country.

Several regions historically refused to bend to this hegemonic script, the Luo, Luhya especially the Bukusu and more recently the Kalenjin after the departure of Moi from the presidency and the Coastal regions stood apart, in that they seemed to favour a relational cultural model of politics built on solidarity, equality, and shared governance rather than transactional bargaining.

From Jaramogi Oginga Odinga's early rejection of Kikuyu dominance in the 1960s to Raila Odinga's, William Ruto's, and Musalia Mudavadi's defiance of Kibaki's transactional politics in 2007, the communities represented by these leaders consistently baulked at the expectation of submission.

Equally significant was the resistance from the Northern Kenya communities which was shaped by their cultural relational context and bolstered by their Islamic religious identity.

For these pastoralist communities, crafting any political altar in the image of Mt. Kenya was unacceptable, as submission to a dominant political centre both clashed with their communal customs and conflicted with a religious ethos that opposed bowing before man-made hierarchies.

Their refusal though quieter than the more overt defiance of the Luo and Coastal regions, has nevertheless been firm and enduring.

Gachagua's political rhetoric, after his impeachment, sought to strongly revive the Mount Kenya hegemonic script. In some media appearances in particular when he featured on Luhya ethnic media channels, he openly framed leadership in terms of regional entitlement, demanding recognition of Mount Kenya as the natural custodian of state power and positioning himself as the gatekeeper to whom others must defer and approach to negotiate to be included in governance of the country post-2027.

But as outrageous as Gachagua's playbook may sound, it hasn't been sustained solely by Mount Kenya. Kenyan history shows that leaders from other communities have repeatedly become enablers of Kikuyu dominance, forcing their people to lie prostrate at the altar of Mount Kenya in hopes of being anointed as future presidents.

Kalonzo Musyoka, Musikari Kombo under Kibaki, Fred Matiang'i in the later Kenyatta years, Simeon Nyachae in his bid for national relevance, Musalia Mudavadi in 2013, all have offered themselves and, by extension, their communities as stepping stones for the perpetuation of Kikuyu hegemony.

To be fair to the mountain, these enablers were not passive victims; they accepted subordination, they helped legitimise a system that diminished their own communities and deepened the stranglehold of Mount Kenya's dominance but the outcome was the same: these leaders were used, discarded, or reduced to political stools, while the real winner remained the continuity of Kikuyu supremacy. The cast may have changed, it is no longer Kibaki or Kenyatta, but the script now runs through Gachagua.

Gachagua's current framing echoes the hegemonic ethos of the elite class in Central Kenya. In his and their worldview, what matters has never been about vision or inclusivity but what each community "brings to the table" and what share of government it receives in return from Mount Kenya.

He is betting on a familiar formula that politics in Kenya can still be reduced to a transaction and is blunt and unapologetic; for him; it is votes in exchange for tenders, loyalty rewarded with appointments, and cash payments deployed as the ultimate adhesive.

The recent political alignments under the “Broad-based” government are fast becoming the counterpoint to the hegemonic politics. At its core, the “Broad-based” government has emphasised inclusivity and relational politics rooted in the philosophy of “compassionate governance” a model that build political legitimacy through shared purpose, trust and belonging rather than fleeting bargains.

Anthropologists studying African societies provide a useful lens for interpreting this shift. They have distinguished between two political cultures; “Transactional” and “Relational.” “Transactional” politics operates on the logic of exchange, it is a short-term system where alliances endure only as long as resources flow. On the other hand, “Relational” politics, draws its strength from building enduring bonds of trust and inclusivity.

These scholars remind us that power in African societies has never been sustained by ethnic transactional mobilisation alone; rather, it has endured peacefully when leaders have cultivated relationships grounded in compassion and inclusivity.

The “Broad-based” government seems an attempt to transcend the limitations of the initial Kenya Kwanza transactional model by fostering a more inclusive, relational-centred form of governance.

It may be that President Ruto, in recognising Kenya’s wider cultural dynamics, experienced a kind of Damascus moment after the 2022 elections, a moment that compelled him toward the idea of a “Broad-based” government focused on the relational political model long embedded in many of Kenya’s communities.

In areas such as Nyanza, Western, and the Coast, political loyalty to figures like Jaramogi and Raila Odinga persisted for decades not because of material inducements, but because of deep ideological affinity and a shared sense of collective struggle. Coastal communities, for instance, focused on kinship ties, faith, and cultural integration rather than from transactional arithmetic.

Similarly, in Northern Kenya, leadership legitimacy rested on clan consensus and Islamic values that discourage submission to hegemonic centers of power.

These traditions illustrated a distinctly African political logic that values relationship and belonging over transaction and expedience.

In many regions of Kenya, politics is not simply a transactional affair, it is a matter of dignity, identity and survival. Gachagua’s model offers none of these deeper bonds.

Transactional bargains may produce temporary alliances, but they rarely generate lasting legitimacy and this is why Kenya’s political history is strewn with the ruins of short-lived elite arrangements built on expediency rather than trust.

Whenever the transactional approach has come up against the power of relational belonging, it has consistently lost and this is the central blind spot in Gachagua’s political project, the assumption that what once worked in backroom pacts, sealed among ethnic kingpins who deferred to Mount Kenya and were rewarded with state largesse, can work again today.

The political terrain, has shifted and the new environment demands legitimacy anchored in inclusion, empathy, and relational trust rather than transactional convenience.

The evolving relationship between President William Ruto and Raila Odinga takes on new meaning, they are coming across as symbols of resistance to Mt. Kenya’s political hegemony.

Ruto, though once allied with the mountain in a transactional bargain, has redefined himself as a leader above ethnic entitlement. Raila, for his part, has been the enduring face of resistance to hegemonic politics, consistently rejecting the notion that entire communities should serve as junior partners in someone else’s political script.

Together, they appear to be rekindling the spirit of 2005, when diverse regions united in rejecting President Kibaki’s brand of transactional politics and in this context, Gachagua’s attempt to revive Mount Kenya’s transactional hegemony presents a paradox.

While it fosters short-term solidarity within his home region, it simultaneously alienates the broad relational partnerships essential for national leadership. His political model, based on entitlement and bargaining, is threatening to reopen historical grievances that have repeatedly destabilized Kenya’s political landscape.

When he frames political alliances as negotiations over “what each community brings to the table” and “what share of government they deserve in return, his recent outreach to leaders from Western Kenya, Nyanza, the Coast, the Maasai, and North Eastern “inviting them to join him” in bargaining for post-2027 government positions with Mount Kenya at the centre reveals a profound misunderstanding of the political culture that shapes many of these regions.

His is the typical approach aligning with the transactional tradition typical of central Kenya, and it is both culturally and politically out of step with the more relational, trust-centered political cultures that predominate across much of the country.

Kenya’s historical experience, anthropological insight, and electoral record all point to the same conclusion: Gachagua’s reliance on a purely transactional model is a grave strategic miscalculation, and it is unlikely to succeed.

The Kenya of 2025–2027 is not the Kenya of 2007 or even 2013. A new generation, particularly Gen Z, has grown impatient with hegemonic bargains and transactional politics and shaped by digital connectivity, economic adversity, and a powerful sense of self-worth, these young citizens refuse to submit to Mount Kenya’s traditional political culture, for them, politics must embody inclusion, transparency, and dignity.

In the rapidly evolving landscape, leaders who seek to tether their communities to the mountain’s altar of dominance will find themselves isolated.

All communities across the country are increasingly asserting their place as equal and active stakeholders in national governance and the broad-based, inclusive, and relational Compassionate Governance approach is the future.

Gachagua’s political strategy a relic of a fading hegemonic order is increasingly misaligned with the Kenya of today. While his message may still resonate in pockets of Nyeri, Muranga or Kirinyaga, it rings hollow in Mombasa, Kisumu, Bomet, Lamu, Garissa, and Kakamega. The nation is steadily moving away from transactional subordination toward a politics of relational belonging.

But he is not alone in failing to grasp the moment, he has managed to draw in leaders like Kalonzo Musyoka, who was similarly enticed by Mount Kenya’s elite in 2007 to enter a transactional bargain, with promises of the presidency in 2013 if he bowed to the mountain’s dominance.

That promise was never fulfilled and now, despite history’s clear warning, Kalonzo appears ready to repeat the same mistake once again lying prostrate, seduced by Gachagua’s familiar flattery, even being called “cousin,” in the hope that a fresh transactional pact will finally deliver him the presidency. It is a déjà vu of political submission, and the lesson, it seems, remains unlearned.

In this new political transition, President Ruto and Raila Odinga have come to embody a broader national yearning, the collective desire for inclusivity and emancipation from the hegemonic politics of entitlement and dominance.

The question is no longer whether Kenya can escape the grip of transactional politics; it is whether those still clinging to the old order can adapt before the tide of change leaves them behind.

For any leader seeking genuine engagement with the country’s majority relational communities, trust cannot be outsourced or negotiated, it must be earned.

Relation building requires time, consistency, and respect for other communities’ leadership structures and not just participation in power-sharing deals.

Raila Odinga's decades-long connection to various communities, despite not holding the keys to state power, demonstrates the enduring strength of relational politics.

Likewise, the legacies of Tom Mboya, Ronald Ngala, and Wamalwa Kijana endure because they invested in vision, trust, and a sense of shared destiny inspiring loyalty not through bargains, but through communal relationships.

In contrast, Gachagua’s transactional script is misaligned with the spirit of a country that is not only relational at its core but also rapidly evolving. A new generation digitally aware, economically restless, and fiercely independent has grown disillusioned with transactional politics. They seek dignity, inclusion, and a shared national purpose, not patronage wrapped in ethnic hegemony.

Gachagua may believe that the mountain still casts a long shadow. But the truth is that Kenya’s political future is already being written elsewhere, in regions and among generations that refuse to kneel before any hegemonic altar.

Mathew Njogu is a Political and social commentator. Email; [email protected]