When I trace the roots of my intellectual awakening, I see the

faces of two men: my father, Clement Fwamba and my elder brother, Nicodemus

Fwamba.

They introduced me not just to general knowledge, but to a

world of ideas, resistance, and radical imagination.

In 1988, my brother joined Cheptais High School. I was in

Class Two. Around that time, I began leafing through The Standard and other

Dailies, which my father bought faithfully.

But it was the

magazines that truly captivated me-their bold cover designs, striking layouts,

and sharp political commentary: Weekly Review by Hilary Ng’weno, The Society by

Bedan Mbugua, Nairobi Law Monthly by Gitobu Imanyara, and Finance by Njehu

Gatabaki.

During school holidays, my brother would walk me through

them patiently, story by story, idea by idea.

But the interest of seeking knowledge didn’t stop with the

newspapers and political magazines.

He began mentioning books he encountered in high school, and

one name towered above the rest: Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

I hadn’t yet read Detained, The River Between, A Grain of

Wheat, or I Will Marry When I Want, but the reverence in my brother’s voice made

Ngũgĩ seem mythical.

He told me how Ngũgĩ defied the Moi government, something

very few would dare then and before that, the iron fist of the Kenyatta regime.

How he discarded his colonial name “James” and declared war

on mental bondage.

How he was detained for his writing and later forced into

exile.

Even before I read a single word of his, Ngũgĩ’s image was

etched into my mind as an unbowed intellectual giant.

Eventually, I read him—and read him deeply.

Alongside Wole Soyinka, Francis Imbuga, Chinua Achebe,

Elechi Amadi and other African giants of literature, Ngũgĩ became part of my

literary canon.

Through him, I learned that the written word could be

sharper than a sword, that storytelling could be rebellion.

Ngũgĩ, my brother told me, had a stammer.

But when he wrote, his thoughts roared. His prose shook

systems. He didn’t just critique power—he dismantled it sentence by sentence.

Even in childhood, I began to understand what democratization

really meant.

What it meant to demand “expanded democratic space.”

Ngũgĩ radicalized my young mind—he made it impossible to see silence as neutral, or oppression as normal.

And then came the stories of student leaders—those who dared

to challenge state power within the university gates.

One name that haunted me early was Tito Adungosi—the SONU

chairman of 1982. Brilliant. Courageous. Arrested by the then-regime. Left to

die in prison under suspicious circumstances.

Another was Wafula Buke, whose story gripped my imagination

even more. Buke, also a SONU chairman, was expelled and jailed at Naivasha and

Kamiti Maximum Security Prisons for

alleged ties with the Libyan Embassy, deemed by the state as subversive.

But to us, Buke was a symbol of fearless conviction. Buke’s

courage, especially, lit a fire in me. I carried his name with reverence.

If I ever made it to

the University of Nairobi, I told myself, I would join that unbroken chain of

resistance—of youth standing tall against injustice.

For many of us, university wasn’t just a place of learning.

It was where ideas collided with action. I became fixated on

joining UoN because it had birthed the stories my brother had fed me—stories of

Adungosi, Buke, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Willy Mutunga, Ali Mazrui, Mukaru Ng’ang’a,

Katama Mkangi.

These weren’t just names—they were monuments of defiance.

Then came 2003.

With Mwai Kibaki’s election, a new dawn broke.

One of his first acts was lifting the cloud over exiles.

Ngũgĩ was invited home. From that year, political exiles

would walk again on Kenyan soil. T

hat same year, the ceremonial chancellorship of public

universities—once a preserve of the president who was Chancellor of all public

universities—was abandoned.

Kibaki appointed Dr. Joe Barrage Wanjui as Chancellor of the

University of Nairobi, distancing academia from direct state control.

It was a powerful symbol: at last, our universities could

begin to breathe again.

As students, we rose.

We demanded the lifting of the SONU ban. We called for the

reinstatement of comrades expelled or suspended during the KANU years. We

wanted our voice back.

And on March 7, 2003, I was elected Vice Chairman of SONU.

It wasn’t just a student election—it was a historical relay.

A generational response.

In many ways, I was carrying the spirit of Wafula Buke into

the office—proof that the fire lit by student activism would not be extinguished

by time, fear, or repression.

Then came the moment that stuck in my memory for eternity.

In November 2004, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o returned.

After over two decades in exile, after teaching at Yale,

NYU, and UC Irvine, Ngũgĩ came back—not just to Kenya, but to the University of

Nairobi—his last place of work before detention and exile. It wasn’t just

symbolic. It was spiritual.

We, the students, received him. It was on the 19th of

November 2004.

I will never forget the energy in Taifa Hall. The air was

electric. His wife, Njeeri, stepped out beside him.

Chants erupted: “Ngũgĩ for Chancellor! Ngũgĩ for

Chancellor!”

As a student leader, I sat on the committee that organised

Prof Ngũgĩ’s welcome at the University of Nairobi.

This gave me an opportunity not only to be part of the team

that welcomed him but was among those who first shook his hand alongside

Chancellor, then the late Dr JB Wanjui, Vice Chancellor Prof. Crispus Kiamba, Dr

Eddah Gachukia, the late Dr. Arthur Kemoli, the late Ken Walibora, Fr.

Wamugunda Wakimani and other student leaders then including the late Oulu GPO.

When I shook his hand—the hand of the man who had

radicalised my mind before I even fully understood the word “radical”—I felt a

great sense of honour and pride.

He spoke slowly. Thoughtfully. Each word hit like a

drumbeat.

Then came his public lecture: “Remembering Africa.”

It was not merely a lecture—it was an awakening.

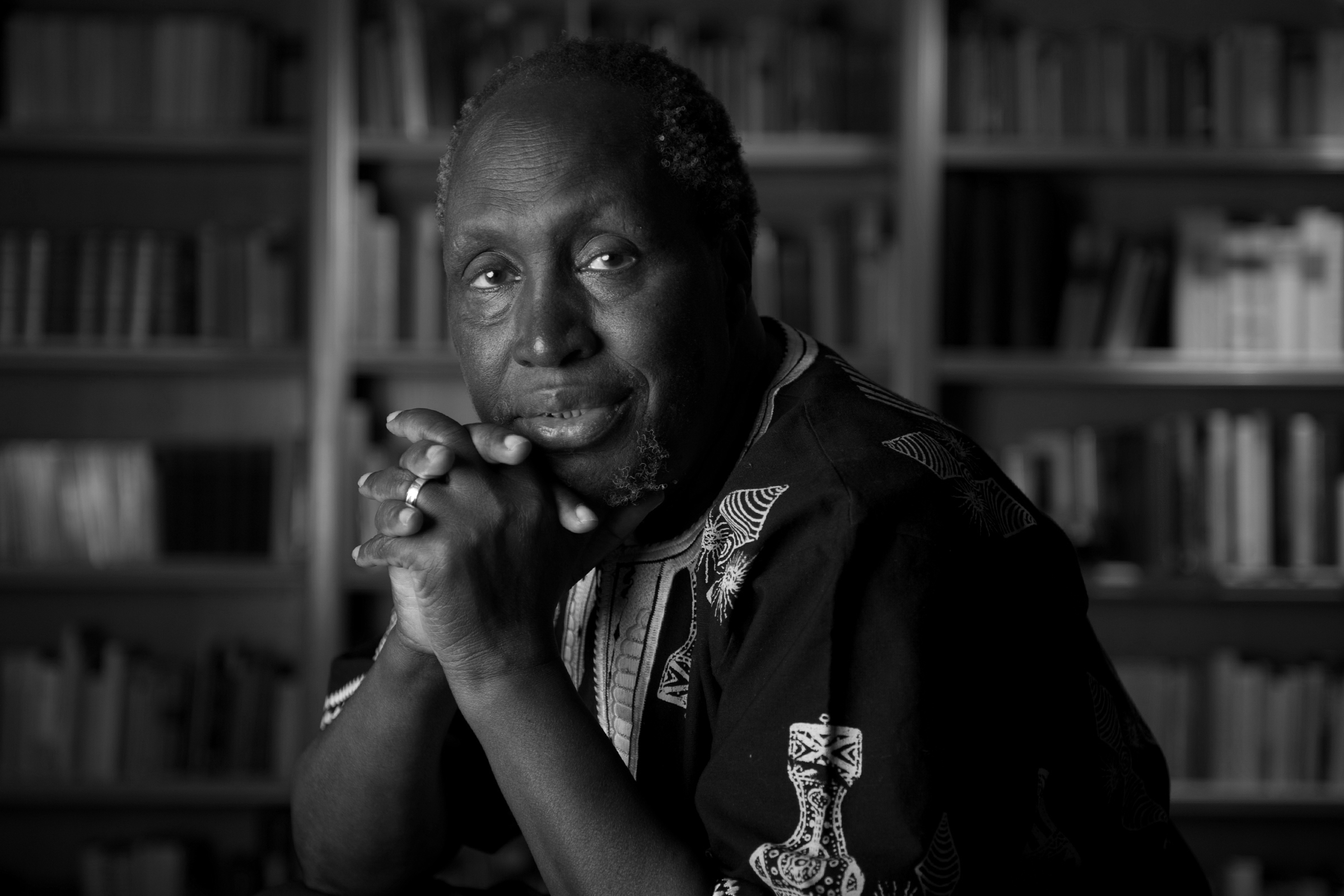

Ngũgĩ, dressed in a simple shirt with striking African attire,

chose to give his lecture while sitting next to his wife Njeeri, whose back he

kept tapping gently as he spoke in a slow manner, not really stammering to the

extent I had expected.

Knowing the background of the man we were welcoming, I also

put on African wear that day. This was before a packed Taifa Hall that trembled

not from noise, but from expectation.

He began not with fanfare but with a story—how the colonial

classroom, church, and prison had worked in unison to separate Africans from

their languages, cultures, and consciousness.

He narrated history, linguistics, and contexts of how Africa

had been interrupted, dispossessed, and misnamed—but never destroyed.

He said Africa had been dismembered, and that is why there

was a need to remember Africa.

He spoke of the African renaissance not as nostalgia, but as

necessity. That true liberation could never be achieved without the reclamation

of language.

That to “remember Africa” was not simply to recall it, but to

re-member it: to piece it back together, spiritually, intellectually,

politically.

He challenged us—students, professors, politicians—to stop

treating English, French, and Portuguese as markers of modernity, and instead

turn to our indigenous languages as vessels of dignity, resistance, and

healing.

When he spoke about the violence of dismemberment—from the

Berlin Conference to the classroom to the publishing house, many in the

audience were emotionally moved.

It wasn’t sadness.

It was the recognition of truth long buried. It was not only

about that truth, but also about the stature of the person who was telling the

story and how he was telling it.

Then came the call: “We must remember Africa to remember

ourselves.”

By the time he finished, no one clapped immediately. There

was a sacred pause, as if we had just come from a baptism of the mind. We left

that hall changed and that's why the lecture is etched in my memory for

eternity.

It wasn’t just a talk. It was a sermon. A revolutionary

prayer. In that moment, Kenya reconnected with a severed part of its soul.

We celebrated Ngũgĩ not merely as a novelist, but as a

prophet.

A truth-teller. A

master teacher of courage and consciousness. His return from exile at that

time was our reawakening as a young generation that

aspired to give Kenya good leadership that was rooted in accountability and

respect for our heritage as Africans, respect for human rights and respect for

the rule of law and good governance.

That year, Kenya’s universities reclaimed their historic

role—not just as places of learning, but as engines of liberation.

And now, as we mourn Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, we do so with

full hearts. Grief, yes—but more so, gratitude.

Kenya has lost a literary lion. Africa, a fierce thinker. The

world, a revolutionary voice.

But Ngũgĩ’s legacy will never die.

Through his unwavering insistence on writing in Gikuyu, his

rejection of colonial psychology, and his fierce critique of imperialism, he

taught us that language is resistance, and storytelling is political.

He taught us to remember who we are. And to fight for who we

must become.

Rest in power, Prof. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

You decolonised our minds. You armed us with words. You taught

us to dream in our own languages. You are home now.

And we—your students, your readers, and those who believed

in your revolutionary ideological points of view—will carry the flame forward.

Fwamba NC Fwamba is

the Chairman of the National Alternative Leadership Forum

![[PHOTOS] Family, friends receive body of Raila’s sister, Beryl](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.radioafrica.digital%2Fimage%2F2025%2F11%2Fdfe6a9bf-ede1-47a4-bdc0-4f564edb03dd.jpeg&w=3840&q=100)