Kenya’s anti-corruption moment feels different—and it should. In a systematic convergence, President William Ruto and ODM leader Raila Odinga have called out parliamentary corruption, puncturing the culture of silence that for years insulated patronage networks.

Their synchronised censure, aimed squarely at the legislature’s darker habits, signals an inflexion point in a struggle that has kept Kenya stuck at 123rd out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

But if rhetoric could end graft, we would be free already. The real test is whether political courage can be converted into prosecutorial outcomes.

Kenya does not suffer a shortage of law; it suffers a shortage of enforcement. Article 10 of the constitution anchors integrity and accountability as national values. The Anti-Corruption and Economic Crimes Act, the Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission Act, the Bribery Act, the Leadership and Integrity Act, and the Proceeds of Crime and Anti-Money Laundering Act form an interlocking regime.

Kenya has also domesticated the UN and AU anti-corruption conventions. Most recently, the Conflict of Interest Act, 2025 tightened the screws—demanding asset declarations, banning compromising gifts and imposing a cooling-off period before public officers can join entities they once regulated. On paper, it is the “reset button” reformers have long demanded.

The Executive has set a stern tone. President Ruto has warned cabinet secretaries of personal liability and rallied multi-agency task forces. Global partners have aligned financing with governance reforms. Yet public trust has not followed. Kenya’s corruption ranking stagnates not because laws are absent but because prosecutions collapse.

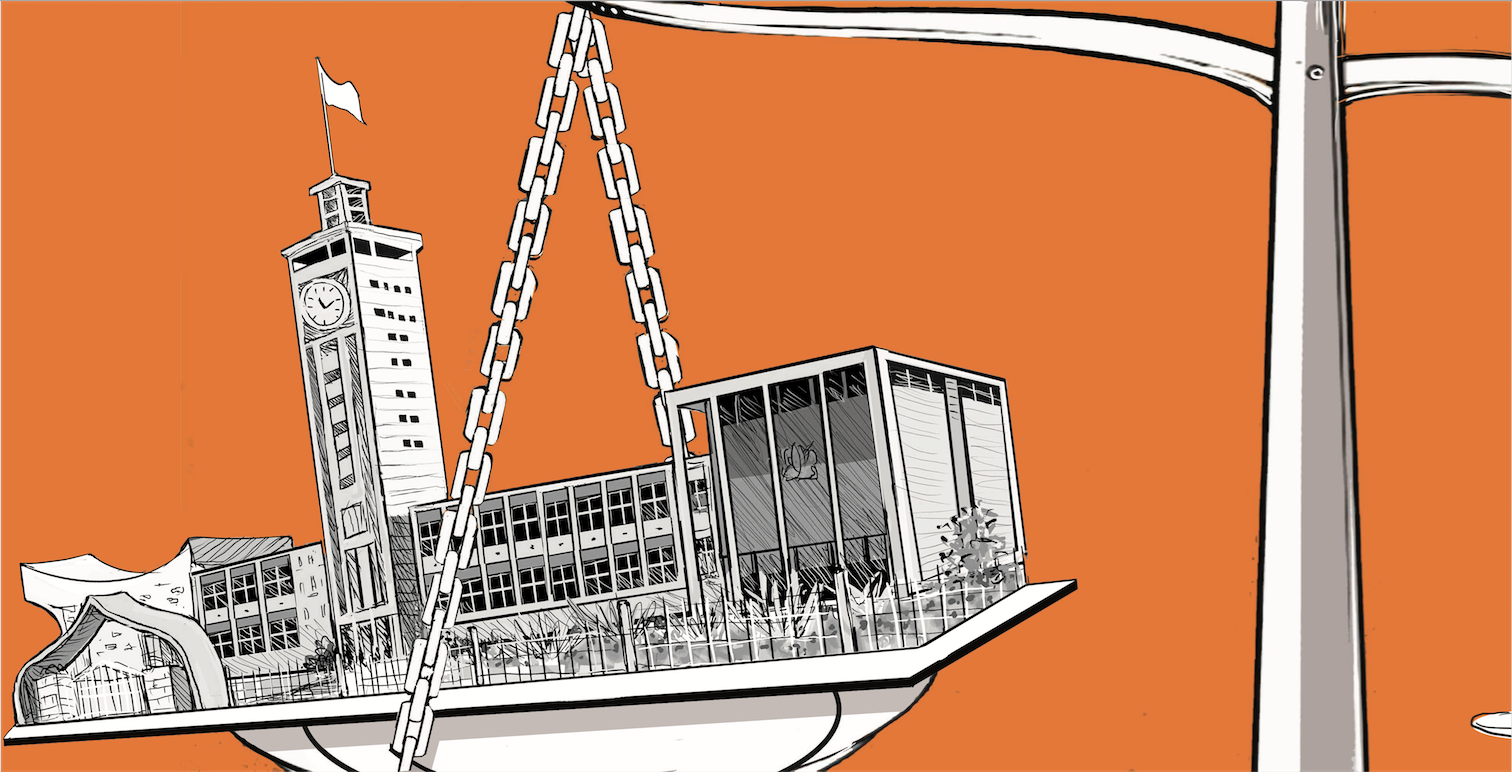

Parliament, long caricatured as a bazaar of influence, now finds itself in the dock. Allegations of MPs soliciting inducements during oversight and the spectre of unexplained wealth have shredded any presumption that legislative scrutiny is always undertaken in the public interest.

Speaker Moses Wetang'ula has conceded that credibility is on trial. The common Kenyan shorthand captures it grimly: there are “egg thieves” in the House and “chicken thieves” in the Executive and parastatals—different scales, same rot.

The Judiciary has also turned the mirror inward. Chief Justice Martha Koome has acknowledged vulnerabilities and sought partnerships with the EACC and intelligence services. Even so, poorly framed charges, weak evidence and procedural ambushes routinely sink high-profile cases.

The weakest link remains

prosecution. The Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions has too

often looked hesitant where the law requires resolve—delays, selective

charging and abrupt withdrawals that defy explanation.

Cases built by the EACC stall in court because files are thin, witnesses are unprotected and political crosswinds distort priorities. The result is corrosive: the EACC enjoys only moderate trust, the ODPP inspires less and the Judiciary bears the reputational cost when flimsy cases are predictably thrown out. Justice then appears arbitrary—even when courts are simply applying the law.

International partners have been

useful catalysts. The IMF and World Bank have tied financing to governance

commitments; indeed, the Conflict of Interest Act helped unlock significant

World Bank support. But donors cannot carry what only domestic political will

can bear. Imported urgency is no substitute for local resolve.

First, prosecutorial independence and capacity must be fortified—not as aspiration but as reality. The ODPP needs airtight case preparation, specialist trial units and insulation from political interference.

Second, witness and whistleblower protection must move from platitudes to practice; without insiders, grand corruption remains impenetrable.

Third, technology should narrow discretion in procurement, licensing and frontline service delivery; digital trails are harder to doctor than paper ones.

Finally, transparency and a free press must be treated as constitutional infrastructure, not inconveniences.

Occasional convictions will not do. The objective is a system where accountability is routine, not news. Parliament must tighten its own discipline and oversight. The Executive must respect the independence of investigative and prosecutorial bodies. The Judiciary must accelerate case management and keep its own house clean.

The Conflict of Interest Act can be a turning point, but only if enforced uniformly and without fear or favour. Kenya has an opening—and openings close. The choice is stark: institutionalise integrity or entrench impunity.

Strategic advisor, political commentator and expert in leadership and governance