Political temperatures are definitely rising, now that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission has been formally constituted, and plans are underway for the many by-elections that have been pending for some time.

And there are many who insist that the outcome of these by-elections will represent a clear indication of how Kenyans are likely to vote in the 2027 general election.

But that is not how Kenyan politics work.

By-elections in Kenya are largely fought, first, on local issues; second, on how much money each candidate spends in trying to get elected; and third, on how much of his prestige the regional political kingpin is willing to invest in steering his favourite candidate to victory.

In by-elections, leading politicians can focus their attention on just a few seats. That is a very different proposition from having to worry about the 290 constituency seats, which are fought over in a general election.

And

that is before you begin to count the regional county seats.

To elaborate on this, the “local issues” often depend on how the seat for which the by-election is being held became vacant in the first place. If, for example, the seat became vacant because a popular leader met an untimely death, then a member of the late politician’s family usually has a definite advantage over all the other candidates.

Then

there is the question of money.

By-elections do not usually generate the kind of political frenzy that general elections so often do. They are relatively toned down, and likely to involve door-to-door campaigns, rather than the “mammoth rallies” that we see in the campaigns preceding general elections.

But this door-to-door campaigning can easily be more expensive than the holding of mass rallies. This is because in going from door to door, it is taken for granted that the candidate (or his key campaigners) “will not leave the people empty-handed”.

Then finally, there is the matter of the prestige and influence of the regional kingpin.

It

is odd that although the Kenyan political system was originally modelled on the

British “Westminster parliamentary system”, when it comes to the selection of candidates

for parliamentary office, Kenyans fiercely oppose the idea that their party

leaders should be allowed to settle on candidates of their choice.

Read just about any memoir or biography of a prominent British politician, and you will find some reference to the man or woman initially having to seek entry into Parliament through a seat they had no chance of winning, and only later being guided to take up a “safe seat” that they were sure to win.

Not so in Kenya. However much the residents may adore their regional kingpin, when it comes to a by-election (and often, in a general election as well) the voters insist on being allowed to make their own choice.

Hence, we have had many cases of regionally powerful political leaders pleading with their supporters in a given constituency not to embarrass them by voting for someone other than the candidate who was running in the by-election on the kingpin’s party ticket.

The usual argument made here is that if the kingpin’s party candidate loses, then it will reduce the kingpin’s ability to negotiate with other regional kingpins when it comes to the dividing of “the national cake” in the next election.

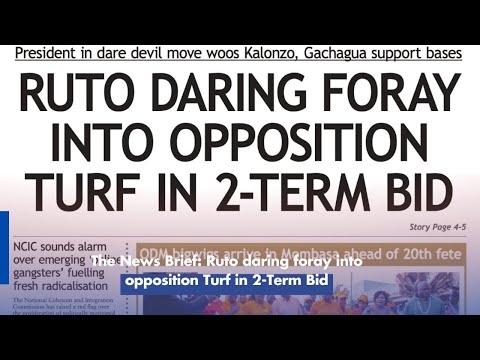

To use a current example, if a candidate for a seat in Lower Eastern (often termed simply as Ukambani) running on a Wiper Democratic Party ticket, lost in a landslide to, for example, a candidate running on the ticket of a small, barely known party, it could be argued that Kalonzo Musyoka’s negotiating strength within the opposition parties would be somewhat diluted.

For Kalonzo’s political influence rests not so much on the fact that he is a former vice president, but rather that the region which has placed its political destiny in his hands, has shown itself faithful in following his political direction, for more than two decades now.

But be all this as it may, Kenyan general elections are mostly driven by regional “waves”. And we cannot know which such wave will support which candidate or party, until about six months before the general election.