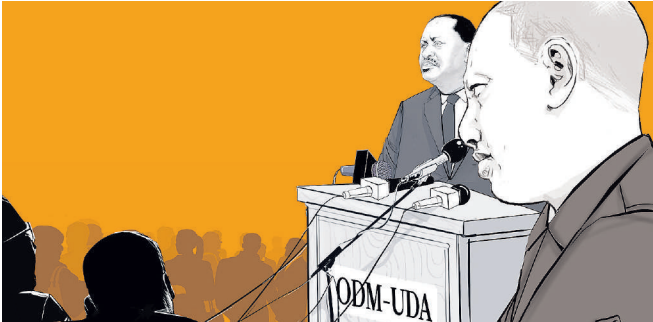

The joint parliamentary

group meeting co-chaired by President William Ruto and ODM leader Raila Odinga

on Monday signifies a turning point in Kenya’s political path. It is more than

just symbolic theatre; it is a reset of our governance structure, rooted in the

March 10-point memorandum of understanding between UDA and ODM. For the first

time, Kenya’s politics is shifting from elite handshake optics to organised,

accountable governance.

Beyond handshakes to institutional change

The meeting commits both sides to implement the Nadco report, entrench budget inclusivity, strengthen devolution, audit national debt and compensate victims of political violence. The inclusion of ODM experts into the Cabinet and the technical committee chaired by Dr Agnes Zani to track MoU progress signals that this coalition is not about positions, but delivery. Unlike past bargains, it represents an institutional shift from zero-sum politics to broad-based governance capable of stabilising a nation long trapped in cyclical crises.

Unity as a diplomatic

and economic asset

Kenya’s fragile economy – ballooning debt, weak revenues and jittery investors – demands political stability as a non-negotiable asset. As President Ruto declared in Migori, the goal is to “create a country for every Kenyan.” Unity is the currency Kenya needs to attract investment, unlock growth and bolster its standing as a regional peace broker.

Three priorities define this agenda. First, a bipartisan consensus on fiscal reforms through a cross-party Fiscal Responsibility Bill to assure predictability and lower borrowing costs. Second, using coalition stability to reinforce Kenya’s mediation leadership in East Africa. Third, addressing the 67 per cent youth unemployment crisis through a “jobs compact” that links opportunity to justice, including compensation for protest victims. The MoU’s 10 pillars – spanning cohesion, devolution, anti-corruption audits and victim justice – provide the scaffolding for these objectives, backed by mechanisms for accountability.

Law as the anchor

Political goodwill alone is not enough. This partnership must be anchored in law to survive electoral cycles. Three legal instruments are urgent. One, a Nadco tracker law, creating a public dashboard with deadlines, answering concerns raised on oversight gaps. Two, a Police Accountability Act, mandating rules of engagement for protests, body-worn cameras and independent probes into fatalities. Three, devolution reform laws, securing county funding floors and revenue autonomy to insulate service delivery from political volatility. These laws would shift commitments from pledges to enforceable rights.

Guardrails against

elite capture

Skeptics warn that

bipartisanship risks weakening opposition oversight. That danger is real, but

avoidable. Three guardrails are essential. First, time-bound legislation – particularly

a 100-day plan targeting cost-of-living relief. Second, citizen co-creation

through structured hearings with youth, business and civil society, to

democratise reform design. Third, judicial oversight of victim compensation to

shield justice from political manipulation. With these safeguards,

collaboration can strengthen accountability rather than dilute it.

From competition

to cohesion

Kenya has seen elite bargains before – the 2008 power-sharing deal, the 2018 handshake – but this moment is different. It is institutionalised, transparent and legislatively actionable. Raila’s challenge – “Judge us in 2027” – is a bold invitation to citizens to hold leaders accountable.

Supporting this initiative requires active public vigilance. Citizens must track MoU implementation, demand tangible delivery and reward bipartisan achievement where it improves lives. If Ruto and Raila use their combined political capital to lower food prices, create jobs and safeguard constitutional rights, Kenya will not merely endure another political pact. It will pioneer a new governance model: unity not as silence or co-option, but as the vibrant noise of collective progress.

At its core, the joint PG is not the end of political competition, but the start of a more mature politics – one that treats cohesion as an asset, not a liability. If Kenya embraces this shift, August 18 may well be remembered as the day we began building not just a joint parliament, but also a joint future.