“Leadership is habits. You wake up today and do the right thing, you do it again tomorrow and the day after, and one day you discover that it’s your nature. The people you lead will see and follow.”

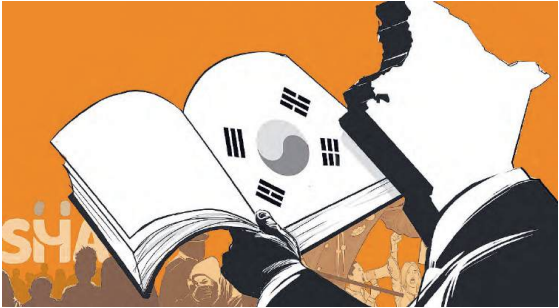

This statement reflects the essence of strong governance and institutional integrity, qualities that were on full display in South Korea’s ongoing political crisis.

The events in South Korea, where the democratic system successfully countered an attempt by President Yoon Suk Yeol to impose martial law, serve as a masterclass in institutional oversight.

South Korea’s parliament, judiciary, law enforcement and civil society acted swiftly and decisively, showcasing the resilience of its democracy.

This stands in complete contrast to the situation in Kenya, where institutional weaknesses have repeatedly allowed opaque deals and mismanagement, particularly in healthcare, to flourish.

In Kenya, the lack of robust oversight mechanisms has led to recurring scandals, particularly in healthcare.

The troubling reality starts with the inspector general of police, who regularly disobeys court orders.

If the office meant to uphold the law defies it, can it serve as a bulwark against corruption by our leaders?

This foundational failure resonates through the broader system.

Allegations of manipulated procurement processes, such as the recent controversies involving HIV testing kits and mosquito nets, highlight systemic corruption.

The Social Health Authority has similarly faced accusations of irregularities and lack of transparency.

Investigations into procurement scandals often drag on, with limited consequences for those involved. For instance, the Kenya Medical Supplies Authority scandals have seen significant public outcry but few tangible outcomes.

Additionally, county governments and other decentralised structures often face pressure from the executive, undermining local autonomy and decision-making processes.

The SHA contracts for equipment supplies, reportedly signed under duress, exemplify this issue.

These challenges erode public trust in governance and hinder the delivery of essential services, particularly in healthcare, where inefficiencies and corruption directly affect lives.

Proponents of reform argue that strengthening oversight is critical to restoring public trust and ensuring equitable service delivery.

Transparent procurement processes, empowered oversight bodies and independent judicial action can significantly reduce corruption and inefficiencies.

However, critics contend that the entrenched nature of corruption and political patronage in Kenya makes meaningful reform difficult.

They argue that powerful interests will resist changes that threaten their control, and without grassroots pressure, institutional reforms may remain superficial.

To emulate South Korea’s success, Kenya must undertake systemic reforms.

Agencies like the office of the Auditor General and Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission need greater independence, resources and authority to act without political interference.

Kenya’s parliament should emulate South Korea’s bipartisan approach, prioritising national interest over party loyalty.

Real-time monitoring of procurement processes can prevent scandals before they occur.

Judicial reforms are also necessary to expedite corruption cases and ensure impartial rulings, building confidence in the judiciary’s role as a check on executive overreach.

Encouraging transparency by safeguarding journalists and whistleblowers who expose corruption is equally important.

A free press and active civil society are vital for accountability.

Strengthening public awareness campaigns can empower citizens to demand accountability.

Grassroots movements, like Kenya’s Gen Z demonstrations, must be nurtured and aligned with institutional reform efforts.

Finally, a comprehensive overhaul of healthcare governance is critical.

Transparent frameworks for healthcare procurement and funding, supported by independently audited digital platforms, can track expenditures and ensure funds are used appropriately.

NICHOLAS OKUMU

Orthopaedic surgeon and a 2024 Global Surgery Advocacy Fellow