Some things are worth repeating, again, and again. With three consecutive failed rainy seasons and a fourth one imminent, the Horn of Africa is facing the worst drought in 40 years.

It is worth noting that delayed response caused the death of an estimated 260,000 people in Somalia between October 2010 and April 2012. While there were early warning signs months in advance, there was no early response.

The world is once again failing to avert a catastrophic hunger in the Horn of Africa. An estimated 20 million across Ethiopia, Djibouti, Kenya and Somalia are facing famine. Urgent appeals are unheeded.

A blistering drought is fuelling a catastrophic food crisis. Hunger and lack of access to safe drinking water for people and livestock have pushed hundreds of people out of their homes. The tragedy is that there is nowhere to go. According to Unicef, 1.7 million children require urgent treatment for severe acute malnutrition in Ethiopia, Djibouti, Kenya and Somalia.

School attendance has plummeted and Unicef estimates that nearly 600,000 children have dropped out of school because of the drought. Moreover, the number of child marriages has increased in drought-affected areas. Data from Unicef shows that some parts of Ethiopia are witnessing dramatic increases in child marriage as parents seek to find resources through dowry payments. Already, nearly 40 percent of girls in Ethiopia are married before the age of 18.

The immediate impact of drought on families and their assets is grave. For example, communities in Marsabit have lost over 70 percent of their livestock, according to the Kenya Red Cross Society. An estimated 1.5 million cattle, goats and sheep died in northern Kenya between October 2021 and March 2022.

Milk production, a key source of household nutrition and income, has declined by nearly 80 percent. Moreover, the overall decline in food and nutrition security is driving up levels of acute malnutrition, especially among children.

In a forthcoming paper in the journal Frontiers in Climate, I present evidence that women have a heightened sensitivity to food and nutrition insecurity security, especially during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Furthermore, the consequences of drought on women range from erosion of household assets to increased risk of adverse sexual and reproductive outcomes.

The effects of drought on food and nutrition security are long-term and even intergenerational, with serious implications for human capital formation.

Poor nutrition leads to problems in brain development. Cognitive capacities such as retaining information and understanding simple processes can be a huge challenge for adults who suffered hunger and malnutrition as children.

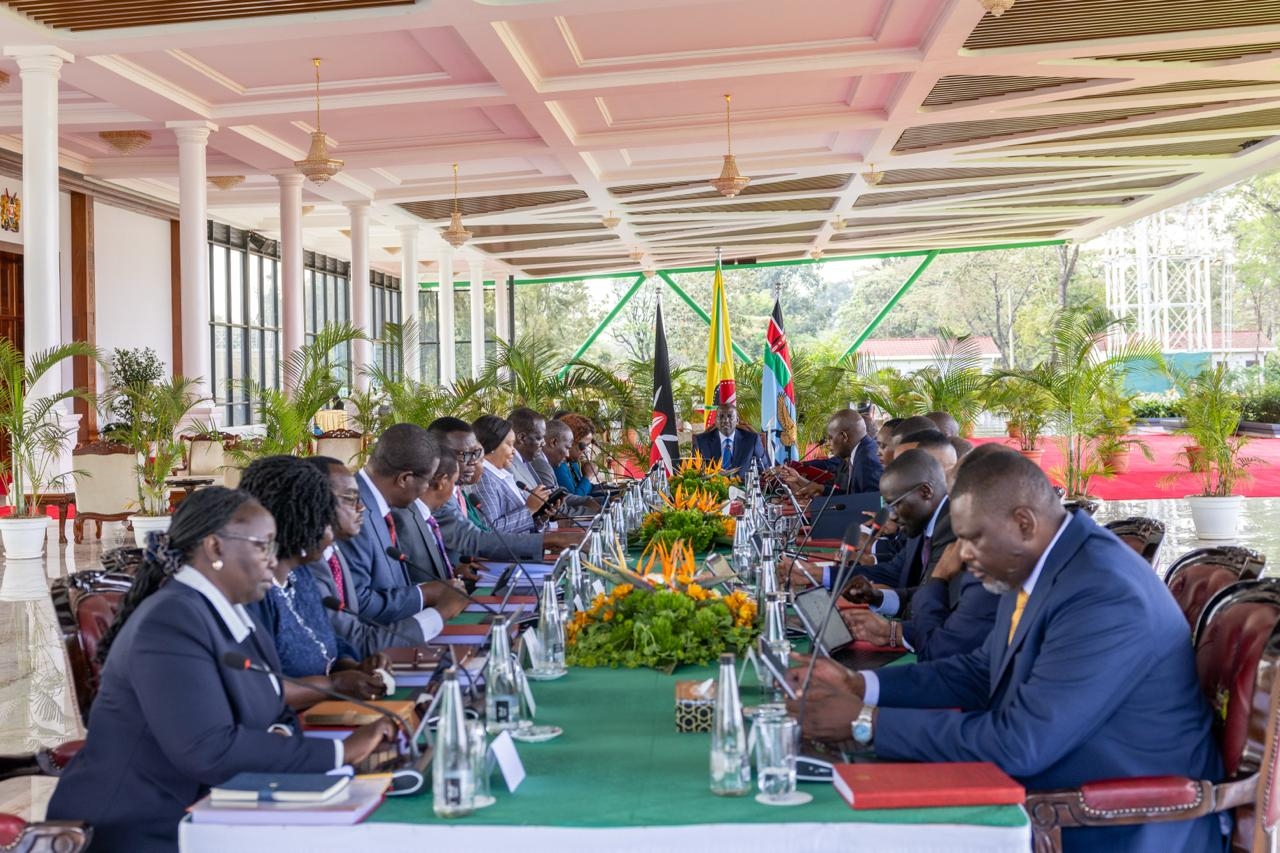

We must mobilise resources to act on drought early warning information. A critical weakness in our response capacity is governance at all three levels; regional, national and sub-national. The fact that we are now dealing with famine, despite early warning, is a damning indictment of our collective governance capacity.

The effect of this blistering hunger will linger many generations later. The effects will be manifested in poor health outcomes, low education attainment and sub-optimal labour productivity.

The view expressed are the writers’

“WATCH: The latest videos from the Star”