Status update of Community Health Promoters

This data is at January 10, 2025

As Kenya reforms its health system, community health promoters remain the first and often only link between families and care.

In Summary

Audio By Vocalize

Community Health Promoters (CHPs)/FILE

Community Health Promoters (CHPs)/FILE

I met Patricia Mutiobo at the Kakamega County social hall during her lunch break, in the middle of a training she was attending on paralegal work, an extension of the role she plays in tackling sexual and gender-based violence in her community unit.

“My name is Patricia Mutiobo, and I serve as a community health promoter.” Her voice was calm but firm, the voice of someone who has spent years both listening and advising, often in matters most people are too afraid to discuss.

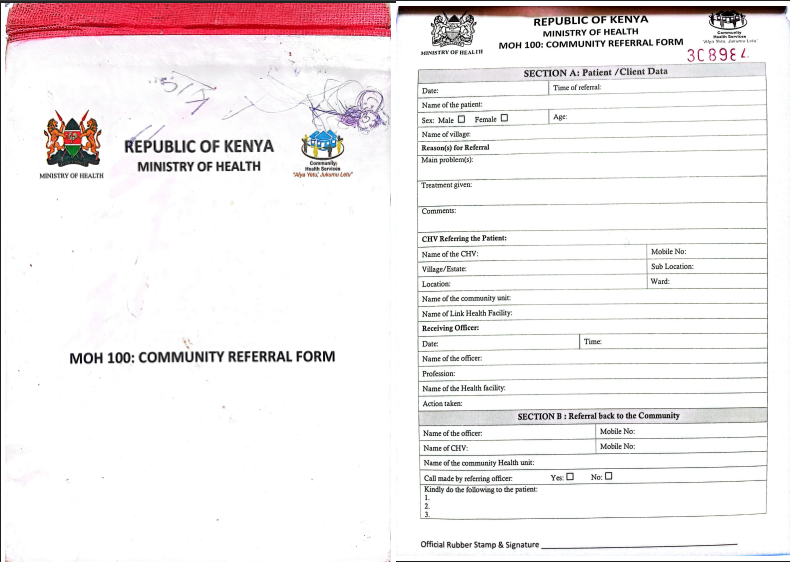

Patricia is a community health promoter under Kenya’s Community Health Strategy (CHS). She works at the Munzakula dispensary in Mayakalo Community Health Unit, one of Kakamega County’s 425 units attached to local health facilities. She supports health talks and facilitates referrals for women, girls, and families seeking reproductive health services.

As a Community Health Promoter, Patricia is the first level of care for these women under the Primary Health Care programme.

Launched in 2006, the CHS was designed to address the critical gaps in access to basic health services in rural and underserved areas, particularly geographical barriers to access, since many households were often far, more than 5 km, from the nearest health facility. It addresses health workforce shortages, as there were too few doctors, nurses, and midwives to meet population needs.

In 2006, when the programme was introduced, Kenya’s health workforce was far below the WHO-recommended threshold of 49 care workers per 10,000 population. Reproductive health outcomes were alarming, and maternal mortality was high.

The programme sought to prevent maternal and child deaths through disease prevention, early detection and referral services; close information gaps in areas like family planning, HIV prevention, nutrition, and sanitation. Overall, empowering communities with knowledge and improving behaviour towards preventive healthcare.

By 2013, the community health volunteer model was transferred from the National government to local, placing counties at the centre of service delivery. With the decline of donor funding from organizations like USAID, many counties struggle to sustain the community health model.

Yet, a few rural counties, such as Makueni and Kakamega, have been making deliberate attempts to keep the model alive. Their efforts reveal both the promise of localised solutions and the persistent challenges of financing and scaling community health across Kenya.

How the Community Health System Works

The community health system operates in a structured hierarchy: coordinators at county and sub-county levels oversee Community Health Assistants and Extension Workers, while Community Health Promoters (CHPs) work directly in communities with support from Community Health Committees.

CHPs are selected locally based on residency, literacy, and community reputation, with replacements chosen transparently through public meetings if needed.

Due to digital reporting demands, a retirement age of 65 has been proposed, but many older CHPs without digital technology skills remain active. Their fluency in local languages and cultural awareness allows them to effectively address sensitive issues, especially in reproductive health.

By engaging in conversations in a familiar, culturally sensitive language and manner, CHPs make it easier for women and girls to discuss personal health issues openly, making health information accessible and respectful of community norms.

A major endorsement for this grassroots programme was the adoption of the model into academic training. The Kenya Medical Training College introduced the Community Health Assistant (CHA) course into the curriculum in 2021, creating career pathways and recognition for CHPs. The shift from purely voluntary work to allocated stipends has also changed the nature and value of work for promoters.

According to Mrs Judith Nyongesa, the Community Health Strategy Coordinator for Kakamega County, under whom the community health promoters model falls, CHPs play a vital role in advancing the county’s goal of bringing healthcare services closer to families.

A Day in the Life of a Community Health Promoter

Patricia begins her work day by reviewing her household register to identify families and individuals in need of visitation.

“I cover a wide range of health issues, but specifically reproductive health. I usually target households that have women and girls who access these services; mainly antenatal care, maternal health, family planning and contraception, and HIV.”

According to the national guidelines, each community health promoter is expected to cover 100 households a month. But Mayakalo is a cosmopolitan ward, with new families constantly moving in.

“I often find myself responsible for more than the standard number, so I prioritise the households that are most in need within a given month. There is no limit to the number of hours I put in every day. Sometimes the work even extends into the night when community members call me for urgent support.” Patricia explains

Her story captures the daily reality of 4,250 community health promoters spread across Kakamega County, the first link in the chain of healthcare, bridging the gap between the community and the health system.

In 2023, the government equipped all community health promoters with smartphones to use the Electronic Community Health Information System (eCHIS) to improve efficiency, accuracy, and follow-up in community health delivery.

To further support their work, the county’s 2025–2026 budget includes providing gumboots, alongside existing smartphones and reflector jackets, to address challenges faced during rainy seasons and ensure safer, more practical household visits in hard-to-reach areas.

For Patricia, building trust is at the heart of her work. She knows that without it, families would hesitate to open up about sensitive health matters.

“Confidentiality is everything,” she explains. “I reassure my clients that I will not share their information, not even with family members. For example, if I am supporting a woman who is married, I cannot disclose any details about her health to her spouse without her consent. Over time, people have come to trust me because they know I have never been reported for breaching that oath.”

That trust is fragile but powerful. Many new clients come to her through referrals from those she has already supported. “When someone tells me, ‘I was sent to you by so-and-so,’ I see it as a sign of confidence in my integrity,” she says.

Gaps in Training, Resources, and Support Undermine CHPs

There are limits, though. Patricia says that most times people refuse to speak to her about sensitive issues like contraception, post-abortion care or diseases like HIV and Tuberculosis; when that happens, she patiently waits until they can trust her or collaborates with former patients who share their testimonies.

“In such cases, I do not force conversations. I give them time. Sometimes I return later, or I invite champions; clients I have supported successfully before who share their stories and help break stigma.”

Training is a key focus for both Patricia and Judith, who see it as the backbone of effective community health promoters' work. Without up-to-date skills, community health promoters cannot fully respond to the evolving needs of households.

“When we recruit community health promoters, they undergo a ten-day basic training,” Mrs Nyongesa explains. “That covers essential health indicators and leadership. Beyond that, there are technical modules, fifteen of them now, covering areas like maternal health, malaria, nutrition, and family planning. But because of limited resources, these modules are rolled out in phases, often with support from partners like Amref Health Africa, USAID and Community Asset Building and Development Action (CABDA).

For many community health promoters, those initial sessions are the only structured training they ever receive.

“Often, reproductive health and family planning training are conducted by partners who could only support a few of us for short sessions, sometimes lasting just two or three days. Without regular refreshers or follow-up training, it is difficult to stay fully equipped to handle emerging issues in the community,” Patricia explains.

She adds that some of the most sensitive but critical issues, like abortion and post abortion care, are not included in government training even though these are recurrent issues promoters encounter within the communities. “Considering the sensitive nature of reproductive health, it is important that we are adequately trained to handle these situations with professionalism and care.”

Another pressing issue is concerns about keeping CHPs motivated, particularly regarding their stipends. When the program began in 2011, CHPs received a modest payment of KSH 2,000 (about $16) per month. This amount later increased slightly to KSH 2,500 (approximately $19.30) at the county level, supplemented by an additional KSH 2,500 from the national government bringing their total monthly earnings to KSH 5,000 (around $39).

Originally, this stipend was based on the assumption that CHPs would carry out their duties during their free time, after completing other personal or income-generating activities. However, this arrangement has become increasingly unrealistic as their workload continues to expand.

According to Nancy Masabiro, who oversees the Virhembe A Community Unit linked to Kakamega Forest Dispensary, “the work has significantly increased and we hardly have time for other things anymore.”

She explains that since Kenya transitioned from the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) to the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), many community members have struggled to register due to misinformation and confusion about the new system.

“Most people do not understand how SHIF works, and without registration, they can’t access services in public hospitals,” she says. As a result, more women are opting for home deliveries, and Nancy is frequently called to assist. A major difference between SHIF and NHIF is that SHIF emphasises a primary healthcare approach, where members are required to be registered under SHIF to access services at level 2 and above health facilities (health centres, sub-county, county, and referral hospitals). This contrasts with NHIF, where patients could still access services in public facilities even without registration.

She adds that the rate of teenage pregnancies remains high, requiring her to follow up with pregnant (and often ignorant) girls to ensure they attend clinics and receive proper guidance. “All these additional responsibilities take up most of my time, yet the stipend we receive is very little and often delayed. We are appealing for an increase because the workload has grown, and the amount we get does not match the effort we put in every day,” Nancy stressed.

“Since 2024, the county has also been paying their health insurance premiums under the Social Health Insurance Fund (SHIF), formerly known as the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF),” Mrs Nyongesa explains.

The payment of stipends is now one of the biggest challenges for community health promoters. Although the national government pays them consistently, the county has owed the workers for so long, Patricia cannot remember the last time she received payment from the county.

There is also a lack of medical provisions.

“We should be able to distribute items like condoms or emergency pills, but we are hardly supplied with them. When the President introduced community health promoter kits, I expected they would include reproductive health supplies. But they did not. To me, that shows reproductive health is still treated as a low priority, yet we talk of reducing teenage pregnancies and HIV infections. How can we achieve that without supplies?”

Another pressing challenge lies in administrative supervision, which the County Health Strategy Coordinator Judith Nyongesa openly acknowledges.

“Every community health unit is supposed to have a Community Health Assistant. In reality, we only have 98 for 425 units. We try to bridge the gap with public health officers, technicians, and volunteers, but it is not sustainable. Also, the community health committees, which should oversee each community's unity, have been left behind. They receive no stipends or training, so their motivation is low.”

Progress, Challenges, and Insights from Regional Models

Within Kenya, Kakamega County illustrates both the promise and the persistent challenges of community health. While the county has made significant strides in training, digital reporting, and linking households to health facilities, gaps in supervision, commodity supply, and remuneration remain.

Kakamega is not alone in facing these hurdles. Across the continent, different community health models from Rwanda to Ethiopia offer lessons in how similar programmes can overcome resource and structural constraints, demonstrating both the challenges and opportunities inherent in bringing health services closer to communities

In Rwanda, for example, community health workers receive performance-based incentives. Payments are tied to measurable outcomes such as immunisation coverage or antenatal visits. This system, combined with strong supervision, has been credited with improving maternal and child health indicators.

Ethiopia offers another model. There, salaried health extension workers are embedded in rural communities and have authority to provide a broader range of services, including family planning commodities. This reduces dependence on referrals and ensures women can access services without unnecessary delays.

Patricia urges for structural support for CHPs, she explains, “Our work is supposed to be done in our free time with small stipends, yet it often takes up far more hours than expected.” She stresses the need for regular training and administrative supervision.

Mrs Nyongesa emphasised that while Kakamega County is developing a Community Health Strategy Bill to address stipends and health insurance for community health promoters, existing community health policies remain limited in scope and lack legal enforceability. She warned that without a legal framework, these measures remain vulnerable to shifts in leadership and funding priorities.

“Unless stipends, insurance, and other support are anchored in law, leadership changes every five years during elections can disrupt everything,” Mrs Nyongesa stated. She further stressed that embedding these supports in the Community Health Strategy Bill is crucial to ensure a strong and effective community health workforce.

Community health promoters are the gatekeepers of reproductive health in the community. By visiting households, answering difficult questions, and guiding women and girls through sensitive decisions, they make services accessible that might otherwise remain out of reach.

This data is at January 10, 2025